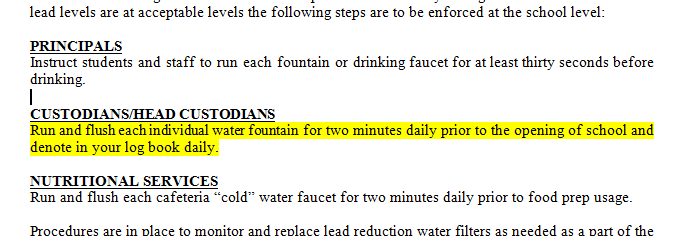

Each September for the past several years, the Newark Public Schools operations director sent a memo to head custodians at all of the district's 60-odd schools, reminding them to run water fountains for at least two minutes each school morning. Then, according to the memo, custodians were supposed to record that action in their log books.

The step was one of the simplest actions a school can take to prevent lead from contaminating drinking water. The running water "flushes" any lead sediment that may have collected in the pipes overnight, reducing children's exposure to the poisonous heavy metal. New York City and numerous other districts around the country have similar protocols, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lists daily flushing as a best practice, given how high lead levels can lead to learning disabilities, brain damage and other ill health effects.

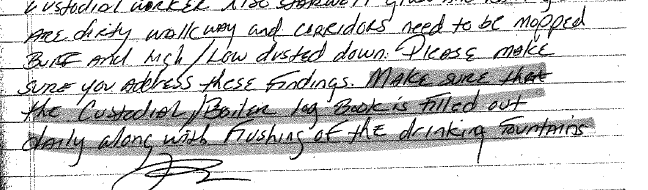

But a WNYC investigation has found that Newark custodians rarely recorded when they ran water fountains, raising questions about whether the flushing gets done in the first place. In a review of log books from 30 elementary school buildings, WNYC found:

- No school building was in full compliance with the requirement to flush and record;

- The log books of only six school buildings complied on more than 60 percent of school days;

- In 14 buildings, or nearly half, custodians did not record having done any flushing at all.

The investigation's findings have implications for other school districts that rely on flushing partially or wholly to reduce the risk of children ingesting lead.

"We should not have the safety of children rely on the faithful implementation across a widespread system of a complicated set of directions," Newark Schools Superintendent Chris Cerf told WNYC. "There are too many risks.”

Newark discontinued the flushing requirement last spring, Cerf said, after an internal investigation determined that custodians were either not running fountains daily or not recording it. Instead, the district has turned off any fountain with a lead level of more than 15 parts per billion, the EPA's standard, and is supplying its schools with jugs of water as needed.

WNYC's review covered logs from the beginning of the 2015-2016 school year until March 9, the day the school district shut off water fountains in 30 schools. The review omitted nine schools which either had illegible logs or which had logs that were not made available through a state Open Public Records Act request. Because some logs were not reviewed, WNYC is not publishing names of specific schools.

In some of the logs, custodians wrote down “morning details completed,” but did not specify that fountains were flushed. WNYC did not consider such notations to be in compliance of the school district's protocol.

Newark, Cerf said, turned out to be the "canary in the coal mine." In the weeks that followed the district's announcement last March of high lead levels, WNYC reported that other districts on both sides of the Hudson River had not tested its public schools systematically for lead in years, including New York City.

The EPA hasn’t changed its recommendations since then. When presented with WNYC's findings on the unreliability of flushing fountains, the agency pointed back to a 2006 document that recommends flushing fountains as an interim measure for schools with lead problems.

"Daily flushing is one of several potential remedies," spokeswoman Enesta Jones said in an email. "However, EPA recommends that each school follow the 3Ts — training, testing and telling — in order to best determine which remedies can best reduce lead in drinking water in that particular school situation."

Any New York City public school that has at least one water source with elevated lead levels is put on a protocol developed by the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, according to school officials. That protocol prescribes a combination of changing pipes and flushing. A spokeswoman added that custodians are required to log every time they run the water, and that the log is inspected monthly by a staff member of the Division of School Facilities.

"We are continuing to evaluate and improve these systems," she said.

The protocol is different from the EPA guidance in one significant respect: instead of flushing the fountains every morning, custodians are supposed to run the water every week, which potentially would allow children who drink from the fountains first thing on a weekday morning to be exposed to lead sediment that had built up overnight. The health department did not respond to a request to explain the discrepancy by deadline.

Research assistance provided by Mary Wang, Nomin Ujiyediin, Camila Osorio, Sarah Gonzalez and Andrew Feather.