The NYPR Archive Collections

The NYPR Archive Collections

Newer Agents in the Treatment of Acute Leukemia

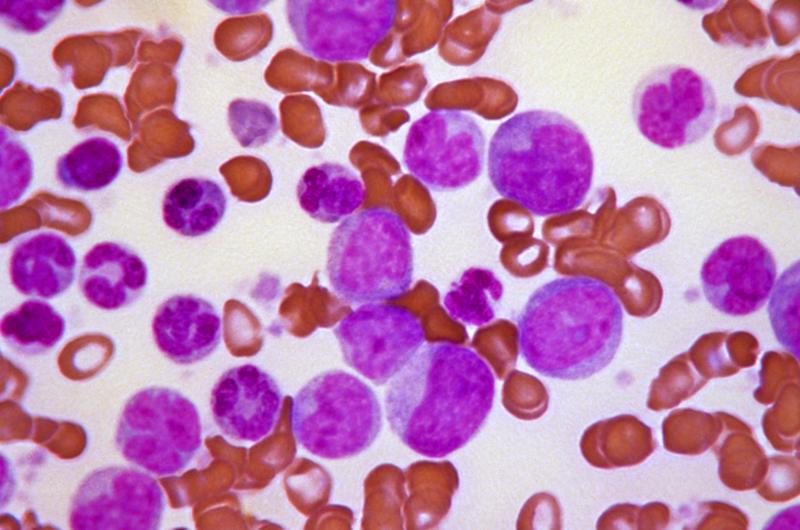

( Stacy Howard/CDC) )

In this lecture, Dr. Sidney Farber gives a presentation on the newer chemotherapy agents used to treat acute leukemia.

WNYC archives id: 67459

(Automatic transcript - may present inaccuracies)

[ Silence ]

>> Mr. Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, it is an honor indeed to be asked to give the Linsly R. Williams Memorial Lecture and to participate thereby in the Laity Series of the New York Academy of Medicine. The fruitful career of Dr. Williams included contributions of great importance to the modern structure of the New York Academy of Medicine which he served as full-time director and also to the leadership of the National Tuberculosis Association. His deep interest in the promotion of the medical education, in preventive medicine, public health and social welfare and in development of basic research to the accomplishment of the goals in these several appeals would have led him quite naturally to the problem of incurable cancer. In the 20 years since his death, tuberculosis which had challenged his talents has begun to fall from its great importance as a public health problem. First, because of the great advances in hygiene and more recently, because of the happy discovery of chemical agents which specifically interfere with the growth of the tubercle bacillus in the human body. And today, the combination of public health control directed toward prevention were possible and early detection of cancer and the application of chemotherapy to the problem of disseminated cancer promises to alter the centuries-old pessimism concerning the problem of cancer in men. Your invitation to give this lecture as a part of the Laity Lecture Series represents an additional challenge. Any discussion on the chemotherapy of the cancer must be based upon the results so recent as to make clear that a lecture on this subject about a decade ago if attempted would have had to be written in imitation of Jules Verne rather than in the form of a scientific credos [assumed spelling]. Your Dr. Iago Galdston, in a masterful short history of chemotherapy entitled "Behind the Sulfa Drugs" published some 11 years ago pointed out that the term chemotherapy which is usually interpreted as the treatment of disease by means of chemical agents had been incorporated for many years in the implications of the word iatrochemistry. The science of chemistry applied to medicine. Ehrlich however had something different in mind. He coined the term chemotherapy not to imply that chemistry was to be utilized in the treatment of the disease but rather in the destruction of the specific disease producing living agents within the body of the diseased being. As Dr. Galdston has phrased it, the aim of Ehrlich's chemotherapy was inner sterilization, actual sterilization within the cell itself. Our discussion tonight therefore is based upon research, most of it no older than 10 years and as recent as this moment but it is only the break through which has come in these last few years. What has been accomplished is based clearly upon contributions made through the centuries and from a variety of disciplines by individuals and institutions scattered over the world. The essence of the most important direction of current research in cancer chemotherapy is a phenomenon of biological antagonism. In his classical paper on the biology of fermentation in 1857 Pasteur laid the foundation for this concept. Pasteur postulated also that a living cell can be inhibited specifically by a definite substance in a selective manner. It was Ringer in 1882 who described in chemical terms the interference between specific ions in biological systems. In 1907, Ehrlich published his theories on specific therapeutics and founded thereby the present-day field of specific chemical inhibition or to use more modern terminology, antimetabolite phenomena. We may define now for our purposes in this discussion the term metabolite as a biologically active chemical substance necessary for the growth of the cell. More recent is the development of the concept of competitive antagonism. In 1935, Dickens give the first clear cut illustration of the adsorption of a metabolite analogue which he explained on the basis of structural similarity of the dyes he employed and coenzyme in negative complex resulted from the replacement of coenzyme by dye. In the following year, Clark explained competitive drug antagonism on the basis of the structural similarity between pairs of mutually antagonistic drugs. The illustration of the metabolite, antimetabolite nature of sulfonamide inhibition accelerated greatly the progress in this direction of research. The theoretical and experimental contributions of D. A. Wooley [assumed spelling] hastened the application to the cancer problem and helped to overcome a delay explained by the pessimism which had hindered research in cancer for centuries. It would be appropriate to introduce these remarks concerning the chemotherapy of cancer by a few comments on the treatment of cancer by methods approved value. The word cancer today it is agreed by authorities in this field is a term used to cover a great many diseases arising perhaps from a multiplicity of unrelated causative factors of widely varying biological characteristics and environmental influences. Wide variation exists too in the life history and biological behavior of these many different forms of cancer. And we should expect important differences in response to treatment. We may compare the different forms of cancer to the many different forms of infectious disease and we find them unrelated as this typhoid fever for example to meningococcus meningitis or pneumococcus pneumonia to staphylococcus osteomyelitis. These are different diseases giving different problems and necessitating different forms of treatment. Although, here in the field of infectious disease there exists today the hope which eventually may be found in the field of cancer chemotherapy that a broad spectrum single substance may affect many different forms of cancer which apparently have different etiologic backgrounds. No discussion of a new approach to treatment should neglect the fact that thousands of patients have been cured through the techniques of the surgeon and to a lesser extent those of the radiologists. The surgeon removed from the body, those masses and attached organs which can be removed with safety after the diagnosis of malignant tumor has been made. The radiologist uses an instrument which results in the destruction of those forms of cancer which are sensitive to a radiation. Whenever it is possible to destroy the tumor which without calling upon the normal tissues to pay a price the body cannot afford. As we now know hormones and chemical agents presently available are, when they are effective, destructive agents too, but in a more satisfactory manner. The ideal treatment for cancer would be one which would supply the malignant cell with the lacking enzyme. The absent trace element, or the needed biological material, which would permit the abnormal undifferentiated tumor cell, first to mature and then to be transformed into normal tissue by those mechanisms which maintain under normal conditions, the contour, and function of the components of the body. We recall here, the extraordinary remodeling of bone under conditions of hypervitaminosis A in the classic experiments of the late Dr. S. B. Wolbach. And we can see in the case of cancer chemotherapy of a similar remodeling and eventual transformation of a chemically treated tumor mass now compose the mature cells and tissues as a consequence of the action of the chemical agent. Such an attack would be aimed at the very essence of the cancer problem if there be one such or to the common denominator of all the different causes of the malignant process. Such an approach, unfortunately, has not yet been made on the sound experimental basis. Ehrlich's definition of chemotherapy, inner sterilization, will be involved in this presentation to include the dissolution of the cancerous process by chemical agents administered to the patient, as well as the possibility of the transformation of the malignant tumor to normal tissue. Now, so molded and fashioned as to fall in with the structural and functional needs of the body. A transformation produced by the administration of chemical materials having the exact biological attributes required for the purpose. That then is the eventual goal of the most rational form of chemotherapy of cancer and one which certainly has not been achieved. In our preoccupation, therefore, with the search for new forms of treatment of cancer, we must not neglect the great strides which have been made in the application of surgical and radiological techniques on the basis of early diagnosis and prompt treatment of the malignant tumor. And in the acceptance of the assumption that cancer is a covering term for a multiplicity of unrelated diseases, there is the implication that we must search not for a cure for cancer, but rather for a series of cures for the various kinds of disease grouped under the term cancer. The need for new methods of treatment is made apparent in several ways. We recognize our inability today to diagnose the presence of cancer in every instance early enough to permit surgical removal before the time that spread or metastasis to distant parts of the body has taken place. There is still no accurate cancer diagnostic test which will permit the demonstration of the presence of cancer somewhere in the body or the examination of a specimen of blood or of other tissue or fluid from the body. This is not to be confused with the extremely valuable Papanicolaou smear tests which are such tremendous practical importance today in the diagnosis of certain forms of cancer which can be reached through the external body orifices or which demonstrate themselves in other manners. Then too, there are a number of kinds of cancer which from the very beginning appear to be widespread throughout the body and therefore, untreatable by the techniques of surgery and the radiation. This group includes acute and chronic leukemia, the various forms of lymphoma or lymphosarcoma, and Hodgkin's disease. The disease acute leukemia, for example, is characterized by the virtual replacement of the bone marrow and invasion of many of the important organs of the body by cancer cells arising originally from those which form the white blood cells of the body. This occurs much more frequently in the child than in the adult. It is responsible for death if not treated within a few weeks to a few months after the onset of the disease.

[ Pause ]

Only a small number of patients untreated live as long as a year. This disease is still an incurable disease despite the great progress in chemotherapy of acute leukemia. In the chronic forms of leukemia, lymphoma, and Hodgkin's disease, the course may run for months to many years with varying degrees of discomfort depending upon the rapidity of the spread of the tumor and the extent in location within the organs of the body occupied by the cancer. For these forms of cancer, incurable or untreatable by surgical techniques, new treatments therefore, have to be developed. All the more, since an estimated 50 to 65 percent of all patients with cancer today cannot be cured by methods of proved value in a smaller percentage of patients. It has long been the hope of those concerned with the sick, that chemicals would be found which when taken by mouth or put into the body would cure the disease widespread throughout the patient. Galdston credits Paracelsus, who lived from 1493 to 1541, Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, for having initiated the science of chemotherapy, a science which was really founded as the science 400 years later by Paul Ehrlich. Paracelsus spoke with the intuition of genius of the chemical arcana where with to drive out the venoms of specific disease. The contributions of Ehrlich have the greatest influence on the chemotherapy of infectious disease. But so fixed has been the pessimism throughout the ages concerning the cancer problem that even as late as 1945, many of the leaders of cancer research paid scant attention to the off dreamed of possibility that cancer chemotherapy could become a reality. Some of this was based upon the disappointment arising from the failure of even the greatest biochemical minds to devise research which could demonstrate important chemical differences between the cancer cell and the normal cell. How then if that were the case could any chemical be expected to act on the cancer cell without equally harming the normal cell? I'm reminded of the remarks of Shields Warren at the second conference on folic acid antagonists in the treatment of leukemia held in Boston in 1951. He recalled the meeting for the Association for Cancer Research some 20 years before. There was a long series of papers on how to produce cancer in mice. And the large lecture hall was crowded. This was the era of carcinogenesis. And great progress indeed had been made in the provision of pure chemical materials which when treated properly, could cause cancer in the mouse. This part of the scientific program was followed by a paper on an attempt to cure incurable cancer in men. Before the speaker could reach the podium, the hall was virtually empty. Dr. Warren pointed out that this was merely an indication of the lack of any lead in the field of cancer research in 1931 which looked as though there might be a breakthrough into the problem of disseminated cancer. How different is the outlook today? And on what does this change depend? The first important contributions came interestingly enough, not from the use of a pure chemical compound but through this discovery that hormones which act as chemical substances provide one great direction of research in chemotherapy. The hormones concerned particularly with the male and female sex hormone and this great direction today is concerned with the alteration of the structure of the male and female sex hormone in order to delete the toxic or untoward defects of these materials and to accentuate at the same time the cancer-destroying powers of these materials. A landmark in the chemotherapy of cancer was the research of Huggins in 1941 in the control of cancer of the prostrate gland by the removal through castration of the male sex hormone stimulus to the growth of prosthetic tissue. This observation suggested the use of castration and then male sex hormone therapy in the treatment of women with cancer of the breast. The use of ACTH and later cortisone in the treatment, particularly of leukemia and lymphoma represents other applications of hormone therapy in the chemotherapy of cancer. The first chemical compound actually used to produce changes in widespread cancer came through a byproduct of research design for an entirely different purpose. Nitrogen mustard, one of the important poison gases and materials of the war, was found in experimental animals to have a profound effect upon the spleen and the lymphoid tissue. Those concerned with this research and with a study of anticancer materials in general, seized upon this observation and found that this poison material when used appropriately in dosage which the human body could tolerate was capable of bringing about temporary striking improvement in certain forms of lymphoma in Hodgkin's disease and more rarely in other forms of cancer too. The first important chemical compound which seemed to have a close relationship to an actual important chemical material needed for the growth of the cells of the body was the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. A whole series of this folic acid antagonist are now known to have important effect in preventing the convergence of folic acid to the citrovorum factor. And these when use in men are capable of causing important temporary improvement in patient with acute leukemia and several other forms of widespread or so called incurable cancer. The importance of the discovery of folic acid antagonist as carcinolytic chemical compound lies in the fact that the whole field of metabolite, antimetabolite research was given tremendous emphasis of the demonstrations that antimetabolite related closely in structure to a substance necessary for the growth of cells was indeed an effective anticancer agent. These were chemically produced through the laboratories of the American Cyanamid Company under the direction of the late Dr. Yellapragada Subbarow has opened new vistas then in cancer chemotherapy. Not long afterward, the demonstration from the research in basic science of men such as Dougherty and White on the effect of ACTH on the spleen and lymphocytes led to the use of ACTH in the treatment first of children with acute leukemia and later other forms of cancer. We now know that ACTH and cortisone are effective hormones for temporary improvement in acute leukemia, particularly in children but also in adults. Within the last two years, a research program in the laboratory of the Burroughs Wellcome Company under the direction of George Hitchings which have been going on for some 10 years in a direction of antimetabolite chemotherapy gave the chemical compound 6-mercaptopurine, purinethol, a purine analogue which in the work of the Sloan Kettering group was found to have striking antileukemic activity joining thus the folic acid antagonist ACTH and cortisone as antileukemic agent. This work was of special interest because it followed a very definite line of reasoning on the part of Hitchings which led him to select purine analogue in an attempt to kill or prevent the--kill the cancer cell or prevent the synthesizing responsible for the continued growth of the cancer cells. How do we select chemical compound today? There are several possibilities. We may begin with a rational approach and this we shall consider briefly a little later or we may take the suggestion made by many people that every chemical compound on the shelf of every chemical factory or laboratory be subjected to chemical analysis and biological screening. If we are to take the second course, it is obvious that we must have a screening method which would tell us accurately that a given chemical has anticancer powers. It must be accurate enough so that further work which is long, tedious, expensive, and time consuming in manpower hours will not be wasted. We also want to have a screen which will be so effective that important chemical compound will not be missed. This problem is obviously not a simple one and it has not been solved. There are several screening methods which are being used today. Under the chairmanship of Dr. Alfred Gellhorn of Columbia University, the Special Research Commission of the American Cancer Society studied the action of 27 compounds in 69 screening systems. A whole series of investigators in various part of the country participated in the study. Many different biological systems gave interesting responses. But in general, it was found that the action of the chemical compound on the transplanted tumor in the mouth in purebred strains gave the most valuable information although correlation with anticancer activity in men is still far from constant or satisfaction. These purebred strains of mice which are employed come to us through the long years of genetic research of C. C. Little and his colleagues in the Bar Harbor Research Laboratory. From these Jackson Laboratories have come not only to purebred strains of mice, which makes this work possible but also the many different forms of spontaneous tumors in the mice which were then transplanted for generation until constant, relatively constant condition could be obtained for screening purposes. The pioneer screening program of Dr. Murray Shear at the National Cancer Institute gave the methodology which helped accelerate similar programs elsewhere. The largest program of this time in a private institution has been carried on for 10 years under Chester Stock and Dr. Rhoads in the Sloan Kettering Laboratory. Smaller, more specific programs directed toward the careful study of certain classes of chemical compounds have been carried out in laboratories of industry and in organizations such as the Children Cancer Research Foundation in Boston. The first method of the routine study of the action of chemical is chosen without discrimination on the growth of selected mouse cancer growing in the mouse has now been brought to the point of study and analysis and sufficient thousands of compounds have been close studied. On the basis of the very small yield it is now possible to create new chemical compounds, analogs of those which have proved to be of interest in the mouse study system. And there is another method which has been of great interest to workers in the field of cancer chemotherapy in the last few years.

[ Pause ]

This concerns the growth of cancer removed from the human being at operation and grown in the Terrien hamster or in the Chinese hamster or in the white laboratory rat. Hundreds of such tumors have been transplanted to the host, the new host, the hamster. A small number of these human tumors can be grown quite readily particularly if the hamster or the rat is treated by irradiation or injected with cortisone at the time the human tumor is transplanted. Attempts are now being made to standardize this test method to permit the study of the action of chemical compounds on human tumors grown in this abnormal environment. And it must be emphasized that this new environment, it does differ in many important ways from the original environment of the tumor. No success can be reported at this time because of grave technical difficulties. If these can be overcome and it is likely that such difficulties will be overcome by research presently in progress in a number of institutions, it may be possible to achieve the hope so often expressed that the ideal chemical compound may be selected for a given patient after the study of all available anticancer substances against tumor grown in the hamster or the rat from the patient whom we now want to treat more specifically than we have ever been able to before. If this is realized there will be much more rationale in the choice of the chemical compound in the treatment of a given patient. We will be treating the exact host as well as the type of tumor from which the host suffers.

[ Pause ]

Before any anticancer substance may be used in men its toxicity and its action on the brain, the kidneys, the liver, the vascular system and other parts of the body, the metabolic activity of the chemical compound, its absorption, excretion and metabolism in the body must be determined by careful laboratory work. It is hoped that many more well equipped and splendidly staffed screening centers and pharmacology study centers will be established in this country in order to produce the basic data so badly needed before anticancer agents can be chosen for use in men with better accuracy than is possible today. There are other methods which are employed in the choice of anticancer chemicals. Microbiological test systems which make use of the growth of bacteria in artificial media, the exact constituency of which is known, contribute greatly to our knowledge of the mechanism of action of those chemical compounds prove to be of importance against cancer by any one of the several approaches utilized. This combination of biochemistry and bacteriology has yielded important data of value to cancer chemotherapy. The value is enhanced by the rapidity with which data of this kind can be accumulated. What kinds of chemical compounds are now of interest in the field of chemotherapy? There are two broad classes which have proved to be of interest on the basis of effectiveness either against tumors in the mouse screening systems or against tumors in men. The first great class of compounds we shall term the antimetabolites. The second are the cytotoxic agents such as nitrogen mustard. The action of chemical agents in general against cancer may be ascribed through an interference with a living process of the cell. Such interference may take place at any stage or at all stages in the development and function of the cell. If cells are arrested in mitotic activity we may not conclude that the chemical necessarily acts by interference with mitosis. The nitrogen mustards, for example, appear to possess the character of cross linking protein whereby cellular functioning proteins are immobilized. This may be called their structural or physical effect. By binding sulfhydryl enzymes that also interfere with cell growth vital respiratory and oxidative enzymes are blocked causing what may be called inhibition of chemical biocatalytic processes. Another effect which has been abundantly studied is the radiomimetic effect, a characteristic which they share with x-ray. The mustards are responsible for depolymerizing deoxyribose nucleic acid which interfere with the structure of nucleic acids of the chromosomes that are to participate in mitosis. Unfortunately, every chemical compound so far proved to be of value in the treatment of cancer in men has encountered sooner or later the phenomenon of resistance on the part of the cancer cell to which had at first been sensitive to the anticancer chemical. Research indicates that this phenomenon which is similar to that observed in the chemotherapy of bacterial infection may be explained on the basis of mutation of the cancer cell which survived. It is quite possible that even the most effective chemical agents may kill only 99 percent of the cancer cell when patients improve markedly and return to a state for a short period of time indistinguishable from normal. This is seen most strikingly in those patients with acute leukemia who show these temporary striking improvements. It is quite possible that the 1 percent of cells which remain or which cannot be recognized by any of our diagnostic methods have acquired resistance to the chemical agent to which all of the other cells have succumbed. And from these resistant cells there will be formed further growth and widespread growth of the malignant tumor. Theoretical possibilities which exist in explanation of this phenomenon of resistance concern themselves with one, a possible alteration and the permeability of the cell to the anticancer agent, or two, to a possible operation in the utilization of the chemical which may become a food for the cell instead of a poison for the cancer cell. And finally, an explanation is offered concerning the utilization of alternate metabolic pathways by the cell which may thus synthesize successfully nucleoprotein by means of a pathway not blocked by the anticancer agent. The solution of the problem of resistance represents one of the most important in cancer chemotherapy if temporary gains, remission or control of certain forms of cancer are to be transformed into permanent cure. The site of action of anticancer drugs may be studied now on the basis of past experience in part successful experience of the last 8 to 10 years. A retrospective glance at the experimental data gained after the demonstration of anticancer affects by several different classes of chemical compounds suggest that chemicals may act in any one of several different ways. There may be an interference with the conversion of folic acid to folinic acid, a citrovorum factor which is required for the synthesis of nucleic acid precursors. Aminopterin and methotrexate act in this way. This does not imply that folic acid causes leukemia or cancer. Folic acid is nearly one of the important cofactors required for the growth of cells. There may be an interference with the synthesis of nucleic acid from preformed purines by substances such as 6-mercaptopurine, purinethol or thioguanine. Or there may be an actual destruction of formed, already formed nucleic acids as is the case with the nitrogen mustard and related compounds. Despite the great advances in our knowledge of the chemistry of the cancer cell and the lessons learned from the action of empirically discovered chemical compounds with anticancer activity. It is still impossible to synthesize on the basis of theoretical considerations alone the ideal cancer compound and know that it will with certainty be effective when tried, nor is there sufficient understanding to permit the assumption that a chemical compound which will be effective against one kind of tumor will be effective also against others. Recent discoveries that certain viruses act as anticancer agents may lead to studies which will show that they act not as living biological entities but nearly on the basis of their chemical structures. The latest promising studies of new chemotherapeutic agents have come from the action of antibiotics against certain forms of cancer in the experimental animal. Antibiotics such as puromycin and certain of the actinomycins have demonstrated at least in the mouse tumor systems striking anticancer effects. This discovery necessitates a large scale screening of every known antibiotic and the search for new tools in an attempt to find anticancer action of new antibiotics and to determine the exact chemical component of the antibiotic responsible for this anticancer action. Such a program can be based not upon a rational approach since the element of fortune plays the dominant role in the discovery of an antibiotic. Such a program however must be based upon expert knowledge, skill and the availability of equipment. I think we may anticipate without question great progress in the search for anticancer antibiotics in the next few years. The chemotherapy of human cancer is now an achievement. Chemotherapy has advanced to the stage of employment of several chemical compounds actually now used in the practice of medicine. These include folic acid antagonists such as aminopterin and methotrexate, nitrogen mustard, purine antagonists and analogs such as 6-mercaptopurine, purinethol, a series of mustard like materials, triethylene, melamine, triethylene phosphoramide and a whole series of related compounds. All anticancer effects produced by chemical agents are temporary in men with the fix lasting from weeks to months, and only occasionally for periods as long as six years. The vast majority of these beneficial effects have been found in the acute and chronic leukemia, in Hodgkin's disease and in the lymphoma group of cancer. A small number of beneficial effects have been produced in tumor such as the neuroblastoma, cancer of the breast and of the prostate, in certain tumors of the brain, and in scattered apparently unrelated cancers in various parts of the body. Such clinical investigations are still in their infancy. There will be great progress in the next few years in the search for action against cancer in men of these anticancer agents now available. A few examples of the effect of chemical agents may be given. Acute leukemia may be profoundly affected by folic acid antagonist, ACTH, cortisone and purine analog either singly, in combination or in sequence with marked improvement resulting in from 50 to 70 percent of children so treated. Such an effect may be characterized by a return to a condition frequently indistinguishable from the normal for periods of weeks, months and in rare cases for years. Here too beneficial effects are terminated by the acquisition of resistance on the part of the leukemia cell. Patients with widespread metastasis and cancer of the breast or the prostate may be improved markedly for as long as three or more years following the use of appropriate hormones. A number of different chemical agents have added comfort if not periods of survival to those suffering from the various forms of lymphoma and chronic leukemia.

[ Pause ]

There is still no chemical cure for those forms of cancer which cannot be cured by surgical or radiological techniques. Clinical experience of the last few years however has shown that chemical agents may on occasion cause previously inoperable tumors to become operable and previously radio-insensitive tumors to become sensitive. It is in this direction that great progress may be anticipated by combined surgical radiological and chemical treatment of disseminated cancer in the next few years. The use of chemical agents as part of total care of the patient with the cancer has improved greatly the lot even of those patients with tumors which do not respond to chemical agents because of the greater amount of care given to the patient as part of such a program. In conclusion, may we speak of the dream of scientist and doctors over the centuries of the treatment of cancer by chemical agents? And may we say that this dream has been realized with the accomplishment of some good results although they are still of only temporary value. Chemical substances are available which when administered to patients with disseminated cancers of certain kind do produce temporary shrinkage and even disappearance on widely disseminated tumor tissue. A continued search making use of either the empirical or the rational approach is certainly justified by this achievement. A solution to the problem of resistance must be found if more lasting results are to be obtained with the agents presently available. The methodology of chemotherapy borrowed from many other disciplines has been whipped into shape within the last few years to facilitate the scientific search for anticancer materials. The possibility exists that an predictable discovery may take place at any time. Those concerned with progress in this field however must depend upon arduous routine, interminable screening and constant testing of hypothesis to be discarded as fast as they are found wanting. There is no shortcut to this work. The availability of scientific methodology used by competent workers in this field points out the requirements for the testing of any claim for anticancer properties or biological materials or chemicals, no date can be set for the eventual discovery of the many cures for the many different forms of cancer. The great progress of the last 10 years justifies their optimistic conclusion that such cures will be found for many forms of cancer through the use of chemical agents or hormones. A plea is made for peace and quiet as well as support for research workers in this field. The National Advisory Cancer Council of the United States Public Health Service through the Office of the Director of the National Cancer Institute has established a committee on chemotherapy of cancer. Now sponsored equally by the American Cancer Society and the Damon Runyon Foundation and supported too by numerous institutions and individuals working in this field. Its purpose is the acceleration of progress in the chemotherapy of cancer and the development of new techniques for the rapid communication of the results of research to all individuals and institutions in the world engaged in this program of voluntary cooperation. There will then be no one V-Day when the cure cancer will be achieved. Progress will be achieved in spurts with great unevenness and non-irregularity. Achievements in one field and then another indeed may become so numerous that they will, it may be hoped, pass almost unnoticed except by the scientific world and the patients who are helped. Anticancer compounds are being used in daily practice now producing effects which would have arouse intense excitement as scant five or seven years ago. The availability of master craftsmen as Huggins has called them of expert and trained scientists in increasing numbers, of adequately equipped laboratories and hospital wards, and of the resources necessary to support a research effort of a magnitude never before attempted in the history of medicine give promise of eventual success in the search for the many cures for the many different kinds of cancer afflicting men. This controlled optimism is based upon the conviction that the accomplishments of the last 7 to 10 years based upon the scientific advances of the centuries have provided the directions for research in the treatment of disseminated or incurable cancer for which we have been waiting. We must remind ourselves that only by carefully controlled research, by critical scientific methodology and by the integration of the activities of pre-research workers from the many disciplines of medicine, chemistry, physics and biology can further progress be made. But the breakthrough has occurred in the chemotherapy of cancer in these past few years. Those who labor in the laboratories of organic chemistry, of experimental pharmacology or physiology far removed from the patient as well as those physicians who are concerned with this new venture in treatment are supported by the knowledge that widespread cancer in the human body can be destroyed even though not completely and be markedly effective even though temporarily by the use of chemicals administered to the patient. And for the patient suffering from what he knows as cancer beyond the reach of present methods of treatment approved value there is the assurance that this activity in the world of research in chemotherapy of cancer guarantees to him that he will not be abandoned.

[ Silence ]