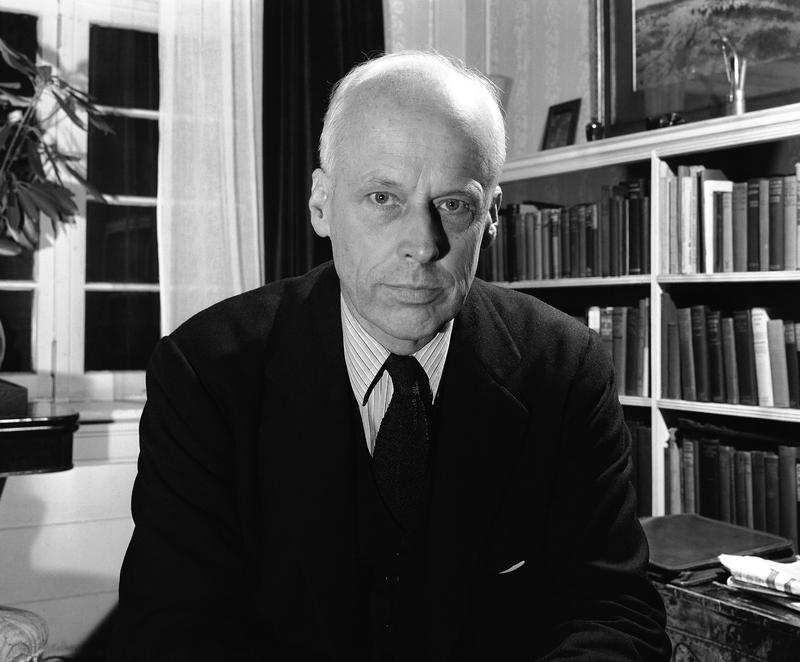

Norman Thomas

Approaching eighty, Socialist icon and perennial US Presidential candidate Norman Thomas surveys the political and moral state of America. Speaking at this 1964 Book and Author Luncheon, Thomas offers an interesting mix of unvarnished pessimism and Christian-Socialist uplift. He is able to discern "no straight moral progress of Man." Indeed, wars of exploitation with their subsequent accumulations of capital are responsible for what we call "civilization." But what are we to do now that large-scale war, with the invention of nuclear weapons, is no longer an option? On the other hand he complains we are not "elated" enough. We do not "rejoice." With technological advances we are in a position to do away with poverty. What stands in our way? The population explosion, because of improvements in health and sanitation, threatens to overwhelm the world's resources. The "religion of nationalism" still leads to small wars, "our time-honored arbiter of disputes."

What he calls for is a massive expression of public opinion, which he insists is fundamentally good. "There is conscience," although, "there is very little excuse for us being as dumb as we are." Specifically, he calls for the passing of the current Civil Rights Bill. In closing, he warns against a pervasive feeling of helplessness, the attitude that nothing can be changed and that it would be best if the whole rotten corrupt system were simply swept away. The biblical Flood, he reminds the audience, was unsuccessful, so why wish for another? Instead he pleads for "…fraternity and, yes, love!"

Norman Thomas (1884-1968) typified the Ivy League-educated gentleman-Radical of the twentieth century. A product of Princeton and the Union Theological Seminary, he started out as a Presbyterian minister before pacifism in the face of World War I lost him his congregation and gained him the attention of the Socialist Party. Thomas eventually left the ministry and developed a distinctive style of political engagement. The Nation reported:

In last autumn’s campaign Thomas made more than sixty speeches in two months, most of them out-of-doors, and he wrote enough words to fill a double-decker novel—all because he had been nominated for alderman by a small local of the Socialist Party in a strong Tammany district. When the votes were counted, an ignorant Tammany optometrist, whose boast was “I never go outdoors during a campaign,” was sent back to the aldermanic chamber with a big majority. And now Thomas is running for President of the United States, as the leader of a party whose death has been officially announced time and again these past few years by conservatives and liberals and extreme radicals alike. No one need feel sorry for Norman Thomas. There is little glory in what he is doing. Long nights in stuffy sleepers, long days filled with speech-making in labor halls, at farmers’ picnics, at Socialist rallies; party conferences; newspaper interviews; pamphlet-writing; handshaking (at which, by the way, in spite of long practice Thomas is still singularly inept)—this is not most people’s idea of a good time. But Thomas is having a magnificent time. He is doing what he wants to do and doing it well.

Thomas ran for Alderman, Mayor, Governor, Senate, and then six times for President. He presented left-leaning voters with a non-threatening alternative to Communism. Although he never amassed the totals of his predecessor Eugene V. Debs, he made respectable showings throughout the Twenties and Thirties and influenced the debate on where the country was heading. As Encyclopedia.com notes:

As the Socialist candidate for president every 4 years, Thomas at least had the satisfaction of seeing much of his program taken over by Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. Many Socialists joined Roosevelt and the Democratic party, others left the party to endorse the Popular Front movement of the late 1930s, and still others left because Thomas opposed United States involvement in the European and Asian wars after 1939. Thomas gave his "critical support" to the American war effort after Pearl Harbor. Yet he also denounced the forced relocation and internment of Japanese-Americans, attacked big business dominance in the war production effort, and argued that Roosevelt's "unconditional surrender" doctrine handicapped prospects for a just and lasting peace.

In the post-War years Thomas became the Grand Old Man of Socialism, a benign, patriarchal figure whose stances prefigured much of the Sixties radicalism to come. This is the Thomas we are listening to here. His views are still uncompromising and perhaps unpopular with the well-heeled audience, but they are presented with all the spirit and optimism of a former minister. As the Educational Technologies Center of Princeton website reports, in a speech given to the students of thirty countries just before his 83'rd birthday he:

…castigated the United States for its policies in Vietnam and its inadequate antipoverty efforts, but he insisted nevertheless that he had affection for his country as well as criticism. He didn't like the sight of young people burning the American flag. "A symbol?'' he asked, "if they want an appropriate symbol they should be washing the flag, not burning it.'' He thought loyalties necessary in life. "Most of us live by our group loyalties . . . but we have to rise above them to the values of humanity so that we can co-exist lest we don't exist at all.''

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 150523

Municipal archives id: RT159