Every year a small group of NYPD officials quietly files an annual financial disclosure form with the city’s Conflicts of Interest Board. It’s only about 130 people out of a department with 35,000 officers, but the forms offer a unique glimpse into the outside financial interests of those running the department.

WNYC reviewed six years’ worth of financial disclosure forms from 219 NYPD officials who filed during that time and used other public records to dig deeper. We found millions of dollars in outside money flowing through the upper ranks of the department over those years.

Among other findings:

- Dozens of top department personnel routinely supplement their six-figure salaries with side jobs and businesses. Some make a few thousand dollars for things like teaching courses at a college or giving speeches. Others made far more. Another two dozen have investment portfolios worth more than $100,000. A few are millionaires.

- In some cases, outside deals and jobs appear to be at odds with department interests. At least one looks like a clear violation of city conflict of interest law.

- The department does not have its own financial disclosure requirement nor investment policy. Meaning, it has no idea how much officers are making on the side, what they’re investing in and the names of people they do business with.

- The city Conflicts of Interest Board only requires about 130 top NYPD personnel a year to report on their finances — outside income, investments and debts. In contrast, the city of Chicago requires all officers with the rank of lieutenant or higher to file an annual disclosure form. There are close to 2,500 at that rank in the NYPD.

WNYC’s review comes as the department grapples with its worst corruption scandal since the 1990’s. More than a dozen high-ranking officers have lost their jobs or been reassigned in the past year. Four cops — including a deputy inspector and a deputy chief — were charged with federal crimes.

Of the 14 officers who have been publicly linked to the federal investigation, only one, ex-Chief of Department Philip Banks, had to disclose his finances to the city. Banks hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing. But he did disclose receiving between $250,000 and $500,000 from an investment firm run by a businessman who has pleaded guilty to corruption and is cooperating with federal prosecutors.

Banks also disclosed hundreds of thousands of dollars from a promotional test-prep company he co-owned. In June, WNYC reported that more than a dozen high-ranking NYPD officials moonlighted in that lucrative industry — charging subordinates for help passing promotional exams. The city’s Department of Investigation is still probing that arrangement.

There’s a long tradition of cops nationwide working second jobs.

“You sort of don’t want to make everything so onerous on police officers and in my view on any government official that it seems like you can't be a normal human being and have the job,” said Matthew Barge, the court appointed monitor for the Cleveland Police Department and an executive director at the Police Assessment Resource Center, a nonprofit that works to improve policing and police-community relations.

NYPD Deputy Chief Kerry Sweet, commanding officer of the legal bureau, said state law allows police officers across New York to work as much as 20 hours a week on another job – as long as it doesn’t conflict with specific city or department rules.

He said the law helps departments hold on to talent who could make more money in the private sector.

“You want to keep that guy as long as you can,” Sweet said, adding that outside income is not unique to the NYPD. “The Mayor of the city of New York has outside rental income.”

To take a second job, NYPD officers must fill out an Off Duty Employment Application and a higher-up must sign off. The application needs to be reapproved every year and officers are barred from taking certain types of jobs, such as working as a bouncer or a locksmith. But they don’t have to disclose to the department how much they make or the names of clients and partners. The department processes nearly 1500 applications a year.

Outside the department, the city Conflicts of Interest Board requires any city employee with authority over policy or spending to file an annual disclosure form. That includes the NYPD, which determines who meets the criteria — typically about 130 department officials each year. City ethics rules also bar certain types of outside interests, including ownership stakes in companies that do business with the city.

Stephen Davis, the NYPD’s Deputy Commissioner for Public Information, said it’s just not possible for the NYPD to look into every outside interest to see if there’s a possible conflict, and officers are expected to follow the ethics rules even if they don’t need to disclose financial information.

“The honor system has to kick in at some point,” he said.

Records show that Davis supplemented his $200,000-a-year NYPD salary last year with a $40,000 a year gig sitting on the board of a publicly traded company called Value Line.

He also earned between $48,000 and $60,000 in referral fees from a private investigator. Davis said he made those referrals from his own private investigations firm before rejoining the NYPD in 2014. He said he got legal advice and approval before making the arrangement.

Sweet was not required to file a disclosure form.

Good work if you can get it

Thousands of pages of financial disclosure forms reveal that the upper ranks of the NYPD have a wide array of outside interests.

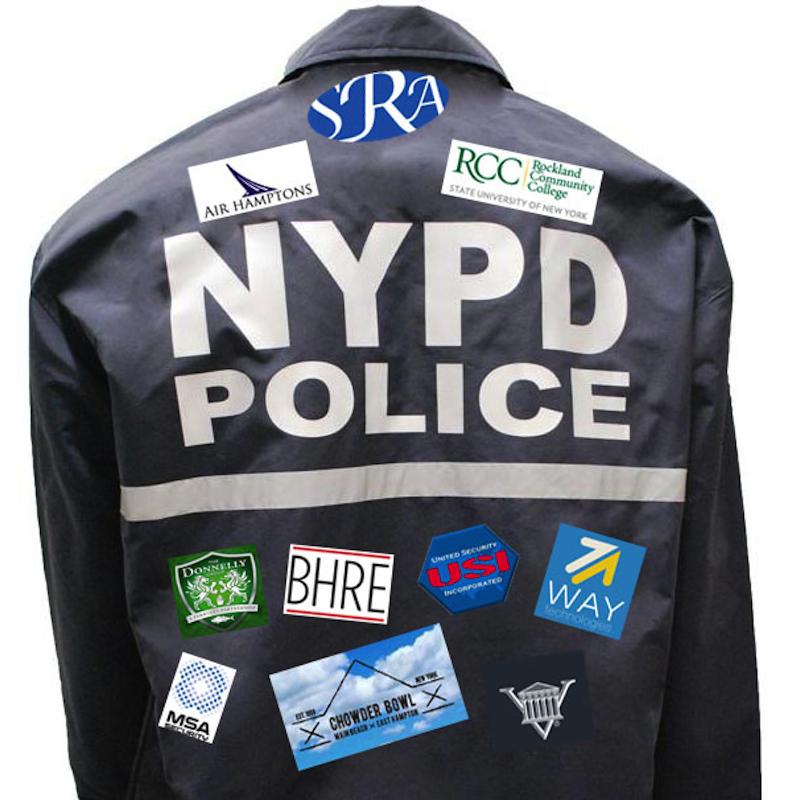

There was a director of operations and communications who had his own computer and consulting business. The head of the harbor unit owns the Chowder Bowl on the beach in East Hampton. A top lawyer started a sun-protective clothing line. Another worked as a blood bank technologist. There are accountants and an estate lawyer, a kitchen cabinet maker and a charter pilot, all making money on top of their public salaries.

Such activities help create a disconnect between the department leaders and rank and file officers, said John Puglissi, first vice president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the city’s largest police union.

“The higher up you go, the more you forget about what it’s like to be the lowly police officer at the bottom of the totem pole,” Puglissi said as he and other officers protested for a pay raise outside a recent appearance by Mayor de Blasio.

Starting salary for a rank-and-file city police officer is about $43,000.

Former-Commissioner William Bratton reported no outside income for last year, although he did allow the New York Police Foundation to pay for his membership at the swanky Harvard Club, as did his predecessor.

Current Commissioner James O’Neill also reported no outside income for 2015, when he was chief of department, the NYPD’s highest-ranking uniformed position. He did report that the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs paid between $5,000 and $48,000 for his trip to Israel with other law enforcement officers from around the country.

Retired-Assistant Chief George Anderson was running the police academy in 2010 when he started moonlighting for a large private investigations and security company called Guidepost Solutions.

Records show that Anderson earned as much as $45,000 from Guidepost between late 2010 and August, 2011, when he retired from the NYPD.

In May 2011, Guidepost was hired to work for the defense in the notorious case of Dominique Strauss-Kahn.Kahn, then head of the International Monetary Fund, was accused of raping a maid at a swanky midtown hotel. He was pulled off an airplane at Kennedy International Airport and arrested by the NYPD.

Prosecutors ultimately dropped the case after the maid’s credibility became an issue.

Douglas Wigdor was one of her attorneys. He said he had no idea a high-ranking NYPD official moonlighted for Guidepost.

“Just the overriding appearance of impropriety is something that causes me some concern,” Wigdor said.

Anderson said he had nothing to do with the DSK case and didn’t even know Guidepost was involved. He said he was hired to evaluate a police department in Bergen County, New Jersey, with three other current and former cops, including former chief of department Joseph Dunne.

“It's an opportunity to participate in something that is useful in terms of your experience in policing, and so your opinion is going to be valued,” said Anderson, who now works for the Port Authority as director of World Trade Center security.

Wigdor said it still seems problematic.

“I understand that police officers have a hard job and are underpaid and need to supplement their income to support their family,” he said. “But I don’t think it should be with companies that have potential conflicts of interest and with entities that could be adverse to the interests of the NYPD and or the Manhattan DA's office.”

Private security is a natural landing place for experienced cops looking to earn outside money. Real estate is another favorite.

Captain Stephen Baymack, commander of the NYPD’s Facilities Management Division, earned as much as $44,000 as a real estate agent in 2010.

He also invested in properties. Records show he bought a home in Frisco, Texas in 2006 and flipped it a year later — to an NYPD Sergeant who also worked in facilities management.

Ethics rules bar superiors and subordinates from engaging in financial transactions with each other. The rules say Baymack shouldn’t have even sold his kid’s Girl Scout cookies to the Sergeant.

Baymack, who has since retired, declined to comment. The Sergeant didn’t respond.

Real and perceived

Michael Cherkasky, a former prosecutor, was chairman of the New York State Commission on Public Integrity and the federal court-appointed monitor for the Los Angeles Police Department in the 2000s.

There’s a tradition in many departments of officers working second jobs, he said. Think off-duty cops working security.

“Police departments do struggle with this on a national basis, because if you in fact shut off all these secondary means of revenue then frequently these police officers are not paid top dollar and you would drive them out of the police department,” Cherkasky said.

But he said the appearance of a conflict of interest can be just as corrosive as actual conflicts – especially for higher-ranking officers.

When he was monitor for the LAPD, he proposed requiring all officers to file annual financial disclosure forms showing outside interests as well as debts. Ultimately, the department required gang and narcotics cops to give such information.

The Los Angeles City Ethics Commission also requires 74 separate positions within the LAPD to file annual disclosure forms with them. Nearly 270 LAPD officials filed with the commission for 2015.

“The lack of trust in people who are carrying guns and wearing badges is something that seriously undermines our effectiveness of policing,” Cherkasky said. “Anything that we can do to build that trust, that is not too onerous, is something that's important.”

But Matthew Barge, the Cleveland Police Department monitor, said conflicts of interest in policing isn’t a hot topic.

After a 50-minute conversation, he said: “This is probably the longest duration of time continuously that I’ve ever talked about the subject, to be honest.”