When people learn I work at a transfer school they often respond with sympathy, saying something like “so you really have it tough!”

Yes, teaching is a difficult craft, and managing a classroom full of adolescents of varying interests and abilities can be challenging, but what most people don’t realize are the advantages I have because I work at a transfer school. My school, West Brooklyn Community High School, runs more effectively than most traditional high schools I have worked in and I consider myself lucky to be here.

WBCHS is for over-aged, under-credited students who are at least 16 years old, are on at least a sixth grade level in reading and math, and had attendance issues at their previous schools. These factors make our student body different, and are what define us as a transfer school.

What we have in common with other New York City schools are issues related to poverty, teen pregnancy, violence, English language skills, literacy and numeracy, peer pressure and bullying, to name a few. Also similar to other schools: our young adults are creative, motivated, kind, supportive, talented, and capable.

On a typical morning, I arrive at the former Catholic school building around 8:15 a.m. and head to the cafeteria for “case conferencing” where all the teachers, administrators, and counselors meet to review our students’ academic, socio-emotional, and behavioral issues. I recently participated in what we call a “roundtable” for a student who is almost 21, has accumulated few credits and, we suspect, has a serious drug problem. We spent about 30 minutes that morning discussing how to keep him safe, communicate his whereabouts with his counselor when he was not in the classroom, and connect him to a rehabilitation facility or other safe place when he transitions out of our school.

Then it’s off to the classroom.

While I am straightening up desks and distributing copies of a book (a recent example: Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian), I hear the counselors at the school entrance greeting students. By this time of the day, many have already spoken to students on the phone, sometimes to wake them up.

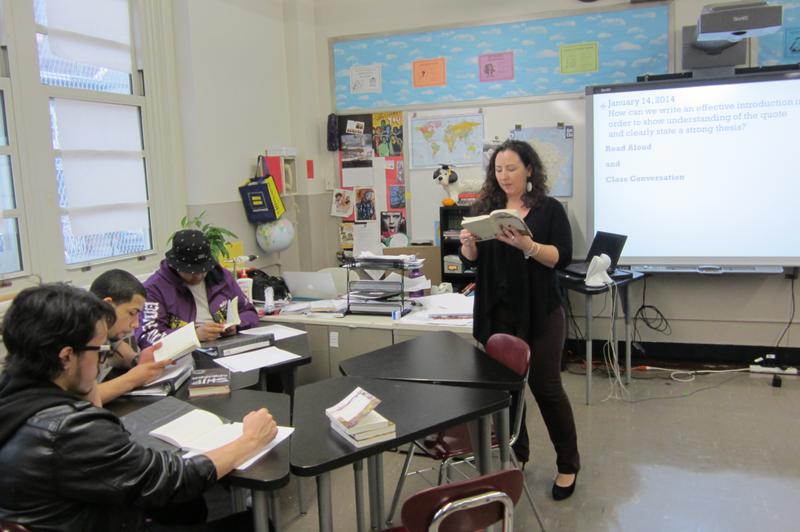

I use a workshop model in my English classes: independent reading, a short writing assignment, a read-aloud, and a class conversation about the text. After this, students work individually or in small groups. We close with an “exit ticket.”

So what makes WBCHS an “easier” (for lack of a better word) school community? It boils down to our systems and structures. Our classes are small: fewer than 26 students per class, with many classes much smaller than that. Each of our students has an advocate counselor with whom they meet on a regular basis. During each trimester we have five benchmarks, giving students a chance to receive their course grades – and meet with their teachers - often.

In addition every teacher in the school uses the same grading policy; faculty and staff help maintain a strong school culture; we use common language to communicate our expectations. Instead of punishing students for academic and social infractions, we conduct mediation. We are a strengths-based school and that culture is evident in everything we do.

That said, we hold students accountable for their work and actions. Absences are unexcused. Students fail to receive credit for missed work without an official note. Problems are not allowed to fester. Frequent meetings between a student, counselor, and teacher are a non-negotiable element of our community.

To make it work, WBCHS provides a great deal of support to the teachers. During my first year, I met weekly with an instructional support specialist to work on curricula and receive feedback and suggestions based on regular observations. Keep in mind, I was no rookie; it was my 10th year of teaching. The vast majority of academic teachers have a prep period at the end of the day, which allows us to collaborate. Department meetings occur weekly; department facilitators and administrators meet monthly.

The counselors communicate regularly with parents and students, in and out of school, allowing teachers to focus on our students and on curriculum development, lesson planning, grading, use of data, and our many other responsibilities.

Yes, teaching is difficult. And exhausting. But just because our students are older and have dropped or transferred out of traditional schools does not mean they are inherently difficult or unruly, at least not more than any other adolescent.

West Brooklyn’s philosophy, culture, approach to relationships, and systems are meant to support all students by building upon their strengths and overcoming their weaknesses, both in and out of classrooms. I know many types of students would flourish in this kind of environment.

I only wish all of our city schools were more like mine.

The series is part of American Graduate, a public media initiative supported by the Corporation of Public Broadcasting.