Preserving Your Favorite Family Recipes

Family recipes passed down from generation to generation are sacred in many households. But sometimes it's hard to get a recipe that was never written down, or try to get a certain recipe from a family member before it's too late. Ahead of Thanksgiving, Valerie Frey, author of Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions, gives us some tips on how to preserve our food heritage, and take your calls.

Title: Preserving Your Favorite Family Recipes [music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Food and family are always on our minds around Thanksgiving. How many of us are looking forward to enjoying or preparing recipes that have been passed down from generation to generation? Family recipes are the backbone of how we gather together and celebrate the holidays, but of course, it's not the easiest to get that stained index card from grandma or grandpa, or the recipe isn't even written down.

Valerie Frey is an archivist, researcher, and author of the book Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions. She's also the author of the forthcoming book Georgia's Historical Recipes. She's here to give us advice on how to preserve our family recipes and to take your calls. Hi, Valerie.

Valerie: Hi. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: Great. Thanks for being here. Let's start with the basic questions. Why is preserving family recipes important?

Valerie: You start to talk about it, it gets personal in a hurry. For me, I lost both of my parents before I was in my mid-20s. It was sort of a crash course in realizing that the generations before us are not always going to be with us. Among the many things that I wished I had asked were how to make some of the things that were important to us. I have a older brother, and it was just the two of us left. How do we scoop up our lives and make holidays feel comfortable and familiar, and how do we pass that to the next generation when we were missing the generation above us?

I was interested in it and began studying how to do that and working with different audiences. I was education coordinator at the Georgia Archives, and so I started including information about recipes in my presentations. It seemed to really strike a chord. I would do an hour-long presentation about preserving all kinds of family materials. At the end, it was the recipes that people would be asking questions about, so I knew I was onto something.

Alison Stewart: What is it about food that makes us feel so connected to our family history?

Valerie: We can talk about Proust and his madeleine, but really what it comes down to is how personal it is. Thanksgiving for me, my mother always made these little round pecan pies. I tried after she was gone to make them. Thank goodness I had her cookbook. Thank goodness she had scribbled notes in the margins, but I still had trouble making that recipe so that it would really taste like hers. I would pass them out at Thanksgiving and everybody liked them, except my brother would give me the side eye and shake his head because it just wasn't quite right.

When I finally did unlock that recipe, I remember my brother, he took a bite, closed his eyes, and stopped chewing. Then his eyes flew open and he said, "Val, this is a little round time machine," and he laughed. My brother, who is a crusty firefighter and former Marine, had tears in his eyes because this was the taste of Thanksgiving. It was the taste of home. It was the taste of our mother's hands returned. I don't know that we can really pin down more than that. I think for many of us, especially the food of our youth or the food of very good times or the food of people that we know love us, it is indeed a connection that brings us back to something important.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, get in on this conversation. What's a family recipe that's important to you and you love to make? How does it make you feel to cook it? Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Where does the recipe come from? How has it been passed down? 212-433-9692. Maybe you have a recipe you love but you're really unsure how to go about preserving it. We can try to help. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call that number or text to us now.

As we wait for these calls to come in, you have a story in your family about a certain stew that your grandfather made to impress your grandmother, and it was quite a surprise. Would you share that story?

Valerie: Yes. My mother, she and my dad met in college. She was from the Pacific Northwest and had never been outside that. She met this guy in college who was from a little rural cotton town, a tiny town in Arkansas, and they got married. My grandmother was sick and so they weren't able to come to the wedding. At Christmas time, my newlywed parents went from the Portland, Oregon area to Arkansas for the first time. My dad was the only child but my grandpa was one of 14, so this little two-bedroom house was stuffed with people who came to inspect the new bride.

My grandfather was the cook in the family after my grandmother got sick. He made his signature stew, which was called Mulligan. After this marathon-long prayer of thanks, my mother finally got the first bowl of soup. She was starving, she said. As the guest of honor, she's given the first bowl. She looks down, and in the middle of the bowl is a little skull. Nobody thought to tell her that it was squirrel Mulligan, and that this was something just so completely ordinary to that part of Arkansas. She was completely flummoxed on what to do.

My father scooped it out. By the way, the brain is a delicacy but it's too tender to survive being stirred in the pot. That's why the skin skull is added, and then you crack it open to get the brain out. My father did that and enjoyed it in her stead. It was a really funny family story. When my parents died, that recipe was one of the first ones that I thought, I got to have this.

Alison Stewart: What can we learn from that? What can we learn from the squirrel stew?

Valerie: [laughs] What I learned was that when I asked my grandpa for a recipe, he just laughed at me because he didn't write anything down. Then he took a stab at it, but he didn't realize how much he knew. He didn't tell me how much liquid to put in the pot, how you choose your tomatoes. Thankfully, he did modify it for chicken, so I didn't have to go to the local park and hunt down any squirrels. He and I did a lot of back-and-forth trying to get this recipe right. The other thing I learned, not just that it takes a little time, but that it's a real pleasure.

My grandpa and I, through phone and through letters, really enjoyed this process. It's brought us closer together and really made me an enthusiast of tracking down those recipes. Even if they aren't always easy, even if they don't always work on the first try, when you are in that process, your hands are doing the motions that someone else has done before you. You're learning bits and pieces. By the time you get to the end of that recipe and you've mastered it, you've mastered a lot of kitchen skills and knowledge at the same time. It's a win-win.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to our elders. We want to find out about these recipes. What are some helpful questions to learn more about a recipe's backstory or how it's prepared?

Valerie: I think just asking those questions. I think a lot of times we expect that people are just going to be forthcoming and tell us things. To ask, why is this recipe important to you? When did this come in the family? Are there any funny stories or warm stories about this food? You'd be surprised sometimes what people don't think to tell you. Then just to take the time to jot that down is very helpful.

Alison Stewart: We got a text here that says, "My grandmother was born in 1900, and she made classic apple pie. I've not found anything as good in the 21st century." Can you explain to somebody why it might taste a certain way initially, and then when we follow a recipe for apple pie, it might not taste the same?

Valerie: I interviewed a lady who was in her 90s, and she said that she hated pecan pie because it was her favorite. I had just like, how do I even unpack that sentence? What she meant was when she was a girl, they had a pecan tree in their yard that had wonderful-tasting pecans that eventually got old and died, and no pecan has ever matched that flavor for her. I think sometimes there are recipes that are somewhat lost to time. The ingredients have changed. I think if it was me, the first thing I would tackle is what kind of apples were used, how could I get that particular flavor back, and just try to break apart the pieces.

Was it the crust that was so good? Do I need to work on trying different types of crust? What was the filling like? Was it really loose? Was it gel-like? That would help you look at other recipes to see what kind of ideas you could bring into it. It is a process, and it is a fun process.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Valerie Frey. She's an archivist and a researcher. She's also authored the book Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions. Let's take some calls. Let's talk to Lori, who is calling in from Teaneck. Hi, Lori. Thank you so much for calling All Of It.

Lori: Hi.

Alison Stewart: You're on the air.

Lori: Yes. I'm calling because I love my Grandmother Hilda, and she made wonderful chicken chopped liver, but I'm a vegetarian. I have changed her recipe to a vegetarian chopped liver, and everyone loves it, I love it. Every time we have it, I think of my wonderful grandmother.

Alison Stewart: Love the story.

Valerie: Oh, good for you. What a wonderful solution.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Suha, I think it is, or Suha, from Hunterdon County, New Jersey. Hi. Thanks for calling.

Suha: Hi. How are you? Thanks for taking my call.

Alison Stewart: Sure.

Suha: I am Palestinian American, and my mom-- and I'm sure she inherited that from her grandma and generations before, we have this traditional Palestinian dish called maqluba. A lot of the families know how to make it, but somehow my mom's was always different and better. I inherited that recipe from her. I didn't marry a Palestinian, so for my in-laws, every time I make it it's like a big wonder. They all get excited. It's always a big wow. Both of my parents passed away, and every time I make it I just remember my mom. I did change it a little bit to accommodate some other flavors, but it never fails. People even request it every time they come over to my house.

Alison Stewart: Love it. Thank you so much, Suha. Following that question, in families, many times a recipe won't be written down, Valerie, but it's passed down from generation to generation. What should folks keep in mind if they're trying to translate a recipe from oral to written?

Valerie: It is somewhat of a process. If you're talking with somebody in real time, it really helps to record it so you can listen later. You can check back and make sure that was three cups rather than a third of a cup, those sorts of things. Then just save that recording because that is a treasure also. Just making sure that you have the recipe as accurately as you can, and then saving stories and traditions attached to it is a wonderful start.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Valerie Frey, archivist and researcher. She's also the author of the book Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions. We would love to know what's a family recipe that you love to make. How does it make you feel to cook it? Where does the recipe come from? How has it been passed down? Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Valerie Frey. She's an archivist and researcher, and the author of the book Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions. She's also the author of the forthcoming book Georgia's Historical Recipes. She's here to give us advice on how to preserve our family recipes and take your calls. Calls like Kevin, who is calling us from Denver, Colorado. Hi, Kevin.

Kevin: Hey. How are you doing, Alison? A shout-out to Lori from Teaneck. I learned this recipe from my mom in Teaneck. I helped her as a little kid with this recipe. It was my job to peel the apples and cut the apples, but she never let me mix the batter. Okay? When she passed away - it's a recipe for apple crisp - I got the recipe, in her handwriting. I have the recipe. Every time I've made it in like the last 10 years myself, my brother and sister say, "Hey, it's good, but it don't look like it and it ain't quite the same." I had experience making this with her, so it's crazy.

Alison Stewart: There might be an answer to that. Valerie, what is one of the answers to why it might not just be the same?

Valerie: With the little pecan pie recipe that I told you about, I realized that I'm a rule follower. When I learned the proper way to measure flour, I fluff it a little, I dump it in a measuring cup and level it off if I'm going to measure by volume. In fact, usually, I just do by weight. My mother just kept her flour in the bag, and she would dip the measuring cup in so was compacting her flour. I realized that hers had a good bit more flour than I thought it should. When I made it her way, with extra flour, that was it. That was what made it taste like it should.

One of the tricks that I have used before is if you go looking for recipes online, there are some great recipe websites out there, find something that's close and then start reading all the comments. When people will say, oh, I tweaked it this way or I tweaked it that way, you may find, hey, that's the tweak that I was looking for to make mine work also. That's a good trick to know.

Alison Stewart: There's also you can use scales. I know that you use scales a lot to try to figure out what's in a recipe. Right?

Valerie: Yes. I am a big fan of using a kitchen scale because I'm a home baker mostly. You can also use your scale as a trick when you're interviewing someone about a recipe. Sometimes these old-fashioned cooks, they'll put in a handful of this or a handful of that. If you try to stop them and slow them down and get them to measure, it breaks their concentration and they get frustrated, and everything is suddenly not working. I discovered that if you weigh all the ingredients before they start and then weigh all the remainder ingredients again when they're done, you know how much they used.

Maybe they're just using handfuls out of the flour bag, but if you weigh it before and after, you will know how much flour they used.

Alison Stewart: Let's take some more calls. Ellen is calling in from Jackson Heights. Hi, Ellen. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Ellen: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. I submitted a song in homage to my mother during the Public Song Project, and you've piqued my memory with this particular episode of her as well. She got married in 1958 and got an electric frying pan as a wedding gift. It came complete with the recipe for frankfurters and noodles. She was not the most gifted of cooks, but her five kids love this. She passed away in 2003. A couple of years ago, I found her handwritten, beautiful cursive recipe of this, and I had it printed on plates for all of my siblings for a Christmas.

Alison Stewart: That is so lovely. Thank you so much. Valerie, this brings up an interesting point. Does it matter what kind of pots or pans that your ancestors used?

Valerie: [chuckles] Sometimes it does. Many of us have heard the folk story of somebody that they always cut the end of the roast off. When they finally asked their mother why they did that, they said the grandmother had done that. They asked the grandmother, she said, well, I had a pan that was too small, so I always cut that off. I think a lot of times we do some of the traditions we do based on the kitchens we have, the tools that we have at the time.

My grandfather used what looked like a frying pan without sides. It was a cast iron skillet that was round. A lot of the magic of his cooking was he'd pull something out of a pot and then get it hot, sizzle edges of a piece of fried fish or whatever on that hot griddle before moving it onto the plate. I had to track down one of those because to get his fried fish to taste the same, I needed that one extra step. Sometimes, yes, you have to go searching and looking.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Donald, who's calling in from the Bronx. Hi, Donald. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Donald: Hi. Good afternoon. My word, I was not expecting to get on. I'm from Guyana, South America, and there's a dish called pepperpot, which is a way of-- It's not quite a stew. It's a cassareep-based preparation where we gather a number of different meats, and it's cooked down in a cassareep base to this wonderful, dark, incredibly tasteful stew. It is designed so that it can be reheated on a multiple basis, and it gets better every time it's reheated. It goes right through the holiday.

Now, my mother was the expert doing this, and I wanted to make sure that this recipe got into the next generation. I got my wife, my daughter, and my sister, and I had my mother up at the house one weekend, and my wife documented the recipe. Now she's transferring it to my grandchildren and my children's spouses, so our pepperpot memories will continue.

Alison Stewart: Love the story. Thank you so much, Donald. Let's talk to Sam calling in from Manhattan. Hi, Sam.

Sam: Hi there. Happy almost Thanksgiving.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Sam: I'm standing here in my kitchen listening to the segment as I fill a pepper grinder that my parents bought in 1961 on their honeymoon in Jamaica. It's not just the recipes. Sometimes it's the tangible object. I also happen to have my husband's grandmother's nut chopper that I pull out every year at Passover to make charoset. Every year I would call my mother-in-law and say I'm using grandma's nut chopper, and she would say, "Oh, I'm so pleased." We lost her this year.

Alison Stewart: Thank you--

Sam: This stuff is very resonant, right?

Alison Stewart: It is.

Sam: The food, the traditions, the generations, what's passed down, it has immense meaning.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for sharing your family story. We really appreciate it. It's possible though to get people together, Valerie, and make a family cookbook. What tips do you have for folks interested in making their own version of family recipes?

Valerie: It's fairly easy to do. There are lots of templates out there if you do a search for that online. There are various companies that make it easy, where they even share a link and everyone can upload their recipes. I think the one thing that I've heard over and over again is people decide to start really big, and then it's a project that they don't end up finishing and they feel guilt rather than pleasure. I always say start one recipe at a time.

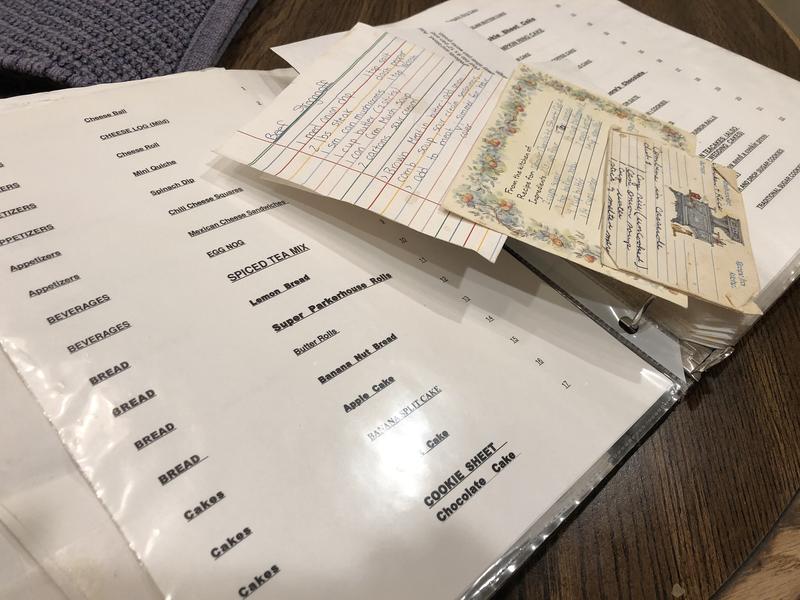

For my son and my nieces and nephews, I gave them nice binders. When I work with family recipes or new things, sometimes at Christmas time, I'm like, "Here's six new pages to put in your binder." I add a scan of the original recipe as an image so that they can see the handwriting. I type it up so that it's workable. I try to put also a photograph of that person and then a little bit of the family history.

My son of course didn't know my parents, and neither did my husband, but they know their faces and they know their recipes. They know a lot of family members by the photos, the recipes, and the stories in that book. It's a great way to connect generations using recipes.

Alison Stewart: This last text, "My family recipe is my great aunt's Parker House dinner rolls. Family lore is that my great-aunt taught my mother how to cook and how to make the rolls. I continue the tradition to make the rolls every Thanksgiving. My family thoroughly enjoys fresh baked bread every holiday." That's a great text to go out on.

My guest has been Valerie Frey, archivist and researcher. Hey, Valerie. Thank you so much for your time today.

Valerie: Thank you. I really enjoyed it, and I enjoyed the stories.