Public Health in the Contexts of its Social, Biological and Medical Origins / Physiological and Ecological Aspects of Public Health

( NYPR Archives / NYPR Archives )

This lecture examines the ecological and physiological aspects of public health.

WNYC archives id: 67358

PUBLIC HEALTH IN THE CONTEXTS OF ITS SOCIAL, BIOLOGICAL, AND MEDICAL ORIGINS*

JOHN E. GORDON

Senior Lecturer (Epidemiology) Clinical Research Center, Department of Nutrition and Food Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass. Professor of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology, Emeritus Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Mass.

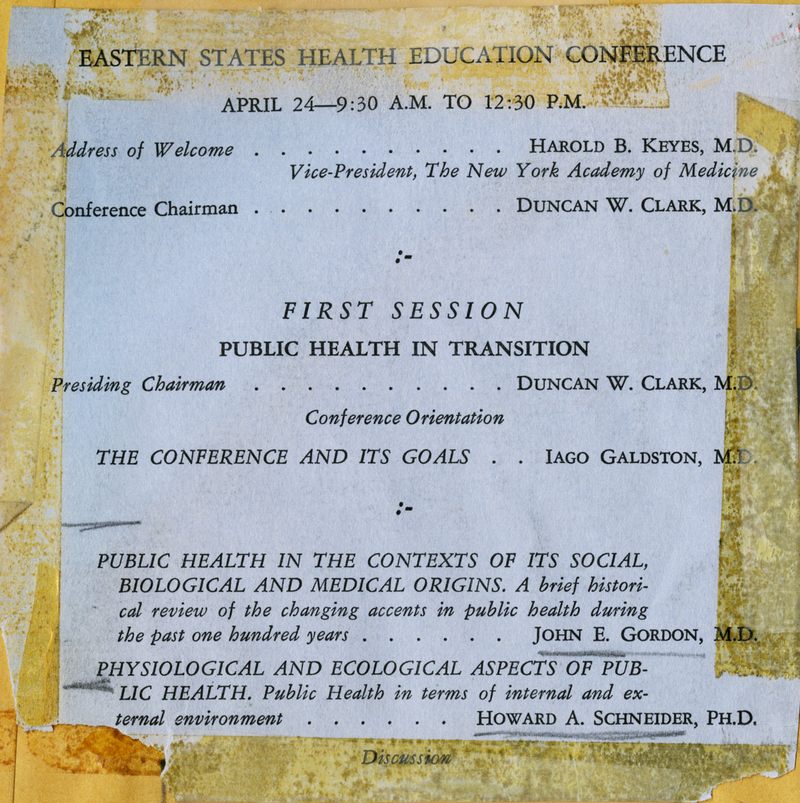

Based on a lecture given at an Eastern States Health Education Conference, held at The New York Academy of Medicine. Contribution No. 820 from the Department of Nutrition and Food Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass.

THE United States ranks well up among the nations of the world in facilities and organization for the public health. The situation was not always so favorable. The country is a young one as countries go. Consequently, attitudes and interests would have been expected to change materially during the past 100 years. What is happening pres¬ently is in support of that assumption. The American Public Health Association for several years has had under way a fundamental appraisal of its various activities, with the objective of realigning its structural organization in order to meet recognized new problems and an altered viewpoint about many old ones.1 Nor is present-day accomplishment in public health so satisfying as to warrant a stabilization of method or thought. Public health in the United States still has a goodly number of weaknesses, and it fails of its potential in altogether too many areas. Public health is changing, has changed, and presumably will continue to do so as the ecologic balance between man and his environment shifts now in one direction and now in another.

A modern public health in the United States may be said to date broadly from about the conclusion of World War I. However, a strong move toward improved conditions had been under way since about 1875, after the discovery of bacteria. The stimulus was largely by way of improved technical method and a better understanding of health processes. The beginnings were much before that, and by no means restricted to an arbitrary 100 or even 200 years. The attitudes and practices of colonial days influenced strongly the subsequent course of events.

*

Colonial America had no health officers and no official agencies for community attention to the public health. So far as health was con¬cerned, community responsibility extended mainly to care of the poor, the unfortunate, orphans, and the mentally ill. Activities of the times thus were mainly in the domain of welfare; yet, along with education, specifically health education, health and welfare are recognized pro¬gressively as indissolubly bound together.2

The ultimate in integration of the three came in 1958 with a com¬bined cabinet post in the federal government, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Each individual interest has the com¬mon objective of promoting the well-being of man, welfare primarily through social means, and health through biological processes. Health education has the function of bringing the two together in a com¬munity endeavor, being largely responsible for the public part of the commonly termed public health. Relative emphasis among the three elements has shifted in the course of years, now one dominant, now another, to such an extent that the developing health movement in the United States can be recognized as falling into fairly characteristic and recognizable periods. The beginning was largely sociologic, then followed a long period with biologic factors dominant and, finally, the situation today is one in which sociologic and biologic factors tend to combine through education to such an extent that public health has been termed the social arm of medicine.

Colonial public health. The communicable diseases were the out¬standing health problems of colonial times3, 4 but control rested mainly in the sociological measures of quarantine and isolation, and applied more to sea traffic than to domestic needs. Fumigation, a rudimentary biologic procedure, also was common practice as a terminal measure designed to rid the environment of the residuals of disease. Little was understood of just how it was supposed to act and against what it was directed. It contributed little and, long ago, gave way to terminal dis¬infection, and that, in turn, to concurrent disinfection, with terminal measures now restricted to ordinary cleaning. Quarantine presently has little emphasis, and isolation has lost its identity as simple restriction of the infected person.

The public health workers of colonial days were individualists largely by force of circumstance, because organized effort was lacking and community direction absent. They were from a variety of pro¬fessions and interests. Cotton Mather was a preacher with a "skill in physic." Benjamin Waterhouse was a physician, and so was the re-nowned Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia. Noah Webster, author of the first American treatise on epidemic and pestilential diseases as they affect communities,5 was a lexicographer; Benjamin Franklin, the leader in health education, was an editor and statesman. These were the outstanding figures in colonial public health. They each approached problems in their own way and independently, except that Rush was too much influenced by his friend Noah Webster: and not always to his advantage, for Webster would have no dealings with contagion. The services provided6 were commonly through charitable or public- spirited citizens and not as a recognized function of government, either local or central. Health committees commonly were formed to meet emergencies, the usual circumstance being one of the recurring epi¬demics so characteristic of those days. As the epidemic waned, the committee tended to dissolve.

When the colonies combined to become the United States of America, and a constitution was written for the new country, public health was ignored as an essential feature of federal government. The guiding principle in health matters seems to have been to let the com¬munity do for itself, rather than have the job done for it, a view of some merit and a commendable pioneer approach. At any rate, public health built up from the roots.

The local health authority. The first organized health agency in the United States cannot be identified with certainty. It definitely was at the local level. The basic structure of the colonial community was that of a closely-knit social organization next beyond the family, a system persisting to this day in the town meetings of New England.

Petersburg, Va., was credited by Chapin7 with establishing the first Board of Health, but proof is lacking because the records were lost by fire. Baltimore, Md., claims that distinction and has evidence that a health officer was appointed in 1793. Boston, Mass.,8 followed soon after, in 1799, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts having given au¬thority for local health services in 1797 but with no compulsion that such services should be established. By 1830, five cities in the United States each had a board of health.9

The persisting rivalry between towns and cities as to which had the first health department is of no great relevance, because for many years all organizations were casual and informal, coming and going with the special need for their services, usually pestilential invasion. As a matter of fact, the early health officers were little more than port quarantine officers, with activities revolving around that area.

So far as the general community was concerned, the emphasis was on cleanliness. Environmental sanitation dominated health activities until well after the Civil War, indeed until the bacteriological era of about 1876. The first objective was control of the communicable diseases, for that was the period of the great epidemics.10 The approach was by way of the physical environment.

State health departments. Most of the colonies from time to time had issued regulations and directions relating to the public health, applicable colonywide but with enforcement a function of the local community. As the states followed the colonies, they too had no authority in health matters. Not until midway in the 19th century did a state government take direct responsibility. Louisiana was the first state to constitute a board of health, in 1855, but as would be expected, it ran into conflict with the local organizations for health, who resented this intrusion of higher authority. In the beginning at least, the Loui¬siana Board of Health was not very effective.

A good many years passed before the next state health department was formed, that of Massachusetts, in 1869. Within immediately suc¬ceeding years, a rash of state health departments appeared: those of California, Virginia, Minnesota, and others. The incentive to their organization was the newly developing knowledge of infectious agents, to permit a more concentrated and direct approach than ever before to the control of communicable disease, still the outstanding considera¬tion in public health. Those were the days when all infectious disease was to be controlled by immunization.

Public health became scientific. In so doing, it lost much of the humanistic character with which it had started. Rather completely it also lost its previous ecologic viewpoint, that the causes of disease were both biologic and social, and that multiple factors enter into the origin of most disease processes. Causality became a matter of an infectious agent.

This changing viewpoint and the rapid accumulation of new knowl¬edge of microbial agents was a stimulus to the organization of more state health departments and to improvement of those then existing.

Laboratories and skilled technicians became a necessity. Field methods were more complicated and, technically, more exacting as they became more precise. The required facilities were beyond the capacity of local communities, except for a few of the larger cities. Thereafter and for many years state departments of public health provided the main stim¬ulus toward improved community health programs. They continue as the solid foundations upon which the public health movement of the United States rests.

A national health agency. The federal government was a long time in recognizing its obligation in health affairs. The first move was the formation of a National Board of Health in 1879. This organization disappeared after a brief and stormy 3-year existence. There was objec¬tion by the states, just as the local communities had objected when state health organizations came into being. The main conflict was with the Marine Hospital Service in respect to port quarantine. The com¬municable diseases still dominated all considerations, and control of traffic by sea had accumulated much tradition as the outstanding fea¬ture of health administration. The Marine Hospital Service itself had existed for many years—since 1798—with obligations mainly related to medical care of merchant seamen, but eventually a responsibility for port quarantine. The National Board of Health disappeared, the Marine Hospital Service regained its functions in maritime quarantine, and the next 25 years saw little progress toward a national health service.

A turn came with the founding of the Hygienic Laboratory in Washington, DC., 1902, to serve the newly created and combined United States Public Health and Marine Hospital Service. The country now had a national center for investigation of disease processes and one for the development of new methods for disease control. A close working arrangement with the states was an early policy, furthered in a practical way by the provision of technical aid in special problems and through field consultation. The original interests were in the com¬municable diseases. Goldberger11 expanded this to include nutrition. In the course of time came the transition to the present National Insti¬tutes of Health at Bethesda, Md., with a separate institution for each of the major fields in a broadened public health program. The Public Health Service Communicable Disease Center at Atlanta, Ga., an out¬growth of World War II, has taken over most of the centralized field work in infectious diseases, with an even closer relationship to the states.

The part of the Hygienic Laboratory in furthering a national health service is definite, and yet progress was by no means continuous nor wholly related to its activities. Not much happened until the Act of 1912, which established the United States Public Health Service much as it is today, through prescribing enlarged functions and responsibili¬ties. These included investigation and research, improvement of meth¬ods in public health administration, federal aid to state and local health departments, and interstate control of sanitation and the communicable diseases. However, the new organization did not really get under way much before 1925. The subsequent years have seen it take leadership in health affairs of the country, at the same time promoting at local and state level the work of the day.

The significance of social factors in health and disease were recog¬nized when the Public Health Service was included in the newly created Federal Security Agency in 1939. Ultimately and within rela¬tively recent years12 this agency achieved cabinet status, has gained enhanced resources and acquired an outstanding position in health research, through its own investigations at the National Institutes of Health and by extensive support of studies at academic and other non¬government institutions.

OBJECTIVE MEASUREMENT OF A PROGRESSING PUBLIC HEALTH

Within the lifetime of most of this generation, public health in the United States has improved in quality so greatly, and its activities are so enlarged, that proof of growth and development is scarcely neces¬sary. Nevertheless, the extent of what has happened is better appreci¬ated when judged by measurements commonly used to evaluate health status. Three useful standards are those of life expectancy at birth, the crude death rate, and the ordered rank of diseases mainly responsible for deaths.

Life was hard in the early days of the republic. The statistics of the time are none too good, and are most satisfactory for those areas where living conditions were best. Of necessity they serve in the present comparison.

Life expectancy at birth. In 1789, the life expectancy at birth in Massachusetts and New Hampshire is recorded as 35.5 years. A little over a century later, in 1900, the value, as expressed by the death reg¬istration area of the United States, had extended to 49.2 years. The

most recent information, that of 1964, gives an estimate a fraction in excess of 70 years, an admirable record exceeded by few countries, and the differences are small. Sweden ranks first with 73.4 years. The Scandinavian countries generally have superior records, along with England and Wales and a number of European continental nations. Canada ranks above the United States, as do Australia and New Zea¬land.

These data for general populations do not reveal the material varia¬tions between the sexes. Males have profited less in the general im¬provement than have females; the best current information for the United States gives a life expectancy at birth of 67.6 years for white males and 74.4 years for white females. The gains for the nonwhite fraction of the population are at lower levels, 61.5 years for males and 66.8 years for females; however, increments in recent years are more than twice as great as for whites.

Crude death rate. Crude death rates (number of deaths per 1,000 population per year) are subject over the course of time to the same influences as is life expectancy. How many persons die in infancy or early childhood is one important consideration. Death is a biological phenomenon but its causes as often as not are sociological. As late as 1725 to 1734, the death rate in the city of Boston was 38.6 per 1,000 population; by 1765 to 1774 it had dropped to 33.5 and in 1841 to 1845 it was 20.3. For the Commonwealth of Massachusetts as a whole, the death rate in 1865 was 20.6.

A death registration area for the United States was established in 1880. With its gradual enlargement, conditions were such in 1900 that the cited rates of 17.2 deaths per 1,000 population have relative reli¬ability and more or less express conditions for the country as a whole. Progress in the first half of the 20th century has been remarkable; a tentative and preliminary rate of 9.4 deaths per 1,000 population was reached in 1964.

Within my memory, communities first reporting death rates below 10 per 1,000 per year were viewed suspiciously, and their mathematics if not their veracity was seriously questioned. Such rates are now usual; many health jurisdictions have records appreciably below that figure. Throughout history, females have fared better than males, the con¬trasting rates for 1963 being 11.1 for males and 8.2 for females.13

Leading causes of death. The nature of the mass disease problems of the United States has altered notably within a century and mainly within the past half century. Some diseases now have far less signifi¬cance than formerly; others have come from an inconsequential posi¬tion to rank high among leading causes of death, or as major factors in lost efficiency or disabling illness. In many instances, what has hap¬pened is more than a difference in numbers of persons involved. The nature and character of a mass disease frequently has changed. From time to time, new diseases have entered the list of leading causes by reason of a shifting ecologic state.

In 1900, 5 infectious diseases were included in the 10 principal causes of death in the United States. Pneumonia was in first place and tuberculosis was second. As of 1964, only one infection holds this important rank: namely pneumonia, along with influenza, but these are now in 5th position. Tuberculosis has dropped to 13th place. The health problems of the community, judged by deaths, are no longer the communicable diseases but the degenerative processes of older persons. Diseases of the heart are a strong first, followed by cancer, vascular lesions of the central nervous system, and then accidental traumatic injury.

When disability and time lost from work are the criteria, the main problems are the common cold, nutritional disorders, and mental ill¬ness. These changes are of such moment as to have altered the whole structure of public health activities and organization.

PATTERNS OF DISEASE IN EVOLUTION

From the beginning of history, and decidely within the last hun¬dred years, new patterns of disease and of disease behavior among populations of people have been in constant evolution. The next pattern to appear is in the making, and it will be succeeded inevitably by an¬other, as man is compelled to adapt to the unfamiliar conditions brought about by an environment that shifts endlessly.

The compelling obligation, if public health and preventive medi¬cine are to be pursued profitably, is to recognize the elements of the current pattern, to note directions of change, to know what has hap¬pened in the past and, perhaps most usefully, to identify the causes of origin and disappearance of earlier patterns.

Mass disease is primarily an ecologic phenomenon, one of the result¬ants of the interaction of man and his environment. Health and dis¬ease, like the fundamental matters of existence and survival, are thereby interpreted as the results of an ecologic interplay that is variously par¬ticular, continuous, reciprocal, or indissoluble.14 Disease in animals, in plants, in any living thing, is looked upon as a maladjustment between a host and the existing environment. Health comes about through estab¬lishment of biological, physiological, and psychological equilibrium, an ecologic harmony. The aim of preventive medicine is to promote that balance.15

The main difficulty in achieving a state of ecologic equilibrium is man's own unheeding manipulation of his multifactorial environment. With the continuing social trend toward industrialization and an urban existence, population density increases. The resulting strain of unhy¬gienic living conditions and hours of exacting work are other contrib-uting factors. Equally significant is the corruption of the moral and intellectual atmosphere in which custom demands that so much of modern life be lived.

The health hazards of the past related mainly to the savagery of the physical environment; to some extent they could be avoided, but mainly they had to be faced in the best way possible. Today, the perils to health are risks many times taken knowingly, often voluntarily, and yet because of advancing knowledge they are to a large extent avoid-able. The diseases of the day, the departures from health, are mainly man-made. They result from the things man does to himself and what he does to his environment. The remedy rests in an improved health education, based on understanding of the ecologic principle that man cannot expect to manipulate his environment without entailing conse¬quences, consequences that are sometimes predictable but frequently not at all apparent at the time.

CONTRIBUTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT

The dynamic nature of mass disease is such that any philosophy of public health must be geared to the environment of the day. Practical programs for prevention and control depend on knowing the limits of man's ability to withstand identified stresses. The cumulative effect of lesser impacts on host psychology and physiology, often delayed in action, are perhaps of even greater moment. An intricate system of checks and balances is operative, a circumstance that compels a view of health and disease as an ecologic process. The approach to public

health is through these principles.

The nature of ertviroTtment. The practical interpretation of en¬vironment long ago escaped its original restriction to simple matters of the physical surroundings. The biological environment, to include all living things other than man himself, carries in its calculations the ele¬ments of food and food supply, a concern that dominates most other determinants of health and disease. This is aside from the animals and plants that serve as reservoirs of infection, or the arthropods responsible for transmitting so many of the great communicable diseases.

The characterization just made, that present-day mass disease is primarily man-made, directly implies that the social component of environment has much importance among causative factors in disease production. The social environment includes those features of man's external surroundings having to do with the association of man with his fellow man.

These several parts of the environment do not stand alone, nor do they act independently. Environment becomes intelligible only when viewed as a whole. The social surroundings have an interlocking rela¬tionship with the physical and, similarly, with that world of other living things, the biological environment, particularly that part having to do with food supply.

Today's environment calls for an adaptation beyond anything man has had to face previously. Not even birds have ventured into outer space, a domain that would seem more reasonably theirs, and yet man pushes that frontier forward day by day. An advancing technology, called into being by the development of ionizing radiation, has brought multiple health problems as a by-product. Modern industry requires exposure to thousands of new and unfamiliar chemicals. All of these matters relate to the physical environment, and yet all have to do with the social environment, for they have emerged through the inventive-ness of man. From a practical viewpoint, they have compelled com¬pletely new techniques in preventive medicine. They are responsible for the new medical specialty of space medicine, mainly preventive in its methods and outlook. Industrial medicine has become dominantly a field within preventive medicine, departing widely from an earlier operational concept of providing first aid to injured employees.

Physical environment. Climate is one feature of the physical en¬vironment that man has had little success in changing. By contrast, the effects that derive from climate have been so modified by new tech¬nologies and changed social systems that the result is almost as definite as if climate itself had been manipulated. Progress in development of clothing has freed man from his early restrictions as a tropical animal, to permit practical existence in temperatures that range from the Arctic to the tropical rain forest. The shape and structure of buildings have been adapted to similar demands of heat and cold, through major refinements in central heating and air conditioning.

The world distribution of land and water, including the proportion of one to the other, has not changed much in the course of contem¬porary time, but the uses to which these elements are put and their productivity have advanced greatly by reason of an improved tech¬nology. Intensive cultivation, the introduction of chemical fertilizers, and especially irrigation have permitted marginal lands to produce in plenty, and even transformed deserts into gardens. Just as definitely, once fertile lands have reverted to the jungle for neglect of such ad¬vantages. Soil conservation has become an integral part of many cul¬tures.

The topography of the land has changed in the course of years, along with the character of the soil. The effects are incident in part to an altered and improved agriculture. They are due as much or more to a developing industry and the aggregation of people in great cities. The building of railroads, followed by the remarkable system of high¬ways that came with the 20th century and the motor car, and eventually air fields, also altered the look of things, but the major consequence was a speed-up in communications. Travel was facilitated to the extent that now it takes less time to go from coast to coast in the United States than it took in colonial times to visit a neighboring town. Distances became shorter as telephone, telegraph, radio, radar, and television came into being. Improved communications had much to do with bring¬ing more effective medical care and, through a better informed public, an enlarged preventive medicine became possible.

Social environment. The community has a geographical habitat; it also has a social structure. People are clustered in families; they are classed by caste and economic status. Social action sometimes results in what approximates mob behavior. People are guided by newly acquired knowledge, influenced healthwise by inventions and discoveries for the control of disease; by tradition, superstition, and mores; by modes of living; and by fads and fancies. They also suffer, on occasion, from a standardization of ideas and attitudes under the impress of cinema, tele¬vision, schools, and the press.

A variety of cultural factors have a bearing on health and disease, on such diverse ideas as those of position, religious and dietary regi¬mens, and on variable practices in regard to personal cleanliness. Some influences are more conspicuous than others, often because they are relatively recent. They include an inclination toward larger familes after an equally obvious trend a generation ago toward a smaller family unit, and also a younger age at marriage. The working wife was unusual 35 years ago and subject to no small prejudice, but now is both ac¬cepted and a common institution. The infectious diseases, so long the dominant consideration among public health problems, now have less significance through the introduction of antibiotics and chemotherapy, an outgrowth indeed of an older and more fundamental cultural influ¬ence, medical research.

Recognition of the true importance of social affairs in the cause and course of mass disease was a long time coming. As so often happens, the result as presently seen is a tendency to overemphasize these mat¬ters, forgetting that the social environment of man is highly condi¬tioned by the presence of other living things, and that the social sig-nificance of our surroundings is deeply imbedded in the physical prop¬erties of the environment.

HOST CONTRIBUTION TO DETERMINATION OF HEALTH AND DISEASE

Stress may be viewed as environmental change brought to bear upon the organism. Man along with most organisms experiences a succession of such impacts throughout life. One result, again among many, is a deterioration of health. Occasionally stress is so overwhelm¬ing that acute illness promptly follows. Again, and with relatively low probability, compensation is complete, the host evidencing neither immediate nor residual effect. The usual result is some level of dys¬function, in the single instance perhaps transitory or even outside ordinary limits of observation, but cumulative when repeated, and conceivably ending in some physiologic or psychologic disorder re¬motely spaced from the initial or early impact. An origin of chronic metabolic and degenerative disease by such mechanisms has been little explored.

The clashes between environment and organism are of more severe moment in those considerable parts of the world where, through newly introduced technologies or the need of other people for their natural resources, a 10th-century society unexpectedly finds itself in a con¬vulsive leap into a 20th-century environment. The shocks are exag-gerated and the costs in terms of disease measurably enhanced.

Health and disease are fundamentally biological processes, and yet the major advances in disease control over the past 150 years are at¬tributable more to improved social conditions and higher standards of living than to any other recognized factor. Particular progress has been made in housing, clothing, and nutrition. The practice of medicine has itself increasingly departed from a concentration on medical care to a concept of preventive medicine, and the success of preventive medicine depends primarily on social action, with education a major weapon of attack.

Whatever the environment, social or otherwise, much of health or disease depends on the nature of the host upon which that environment acts. The host is no more static than the environment, and no more uniform in characteristics evidenced from one part of the world to another. Qualitatively, the social group is different from the sum of its parts.

At best, the organism must adapt if it is to survive, and with adap¬tation comes intrinsic and constitutional change.16 The result is a present-day human host far different from the creature recorded in the beginnings of history; moreover, one departing importantly in suscep¬tibility and resistance to a variety of ills, even when compared with ancestors no more remote than 100 years ago.

HUMAN ECOLOGY IN ACTION

If environment has altered perceptibly with time, if man has taken on different and sometimes new characteristics, it follows that the inter¬actions of these two elements as exemplified in mass disease should lead to a different kind of result. That the health problems of the present are so often not those of other days, that they are many times unique, thus comes as no surprise. Furthermore, as civilization progresses and society becomes more complicated, man increasingly takes a more prominent part in determining the ecologic balance that makes for health or disease. It is for such reasons that current community disease

tends to be so much man-made.

A considered understanding of present-day mass disease requires that those features of both host and environment that have remained essentially unchanged in composition and form be distinguished from those that have changed and, in turn, from those in the process of changing.

The direction of change in mass medical problems of the population of the United States is better illustrated by a consideration of health areas rather than specific disease conditions. The relative and changing importance of individual diseases is reflected satisfactorily in the rank order of the causes of death already presented. The greater significance rests in the fresh areas of health concern that have resulted from altered ecological relationships. Each of the several areas now considered has a variety of individual problems, all dependent to a measurable extent on the particular ecologic principle that permeates the association.

Population pressure. A true evaluation of population pressure, as probably the main world health concern of the day, is inhibited by an attitude common to both amateur and professional workers in the health field: that health is properly judged in terms of specific illnesses. The World Health Organization, by title and stated objective, is concerned with health, and yet its major activities are not with health but with a variety of diseases that disturb health, at least a backhanded approach. The ordinary official health agency of the community in the United States also is concerned chiefly with the control of a communicable disease, a cancer program, or the measures to be taken to combat dia¬betes or heart disease.

On the contrary, the major menace to a healthy world society would seem today to be too many people or, stated more exactly, the pressures arising from accumulated numbers of people greater than the existing natural resources, the cultural demands, and the social stand¬ards of a country adequately can accommodate.

Historically the population problem is of relatively recent origin. For centuries there was no problem; so far as records permit judgment, the population of the world continued for long periods at fixed and relatively low levels. An abrupt increase developed about 200 years ago, but as late as 1856, after 5,000 known years of civilization, the population of the world was still only about 1 billion persons. The numbers doubled in the next 70 years, and reached 3.2 billion in 1963.

With a present world increase of 1.9 per cent annually, the projection for 1980 is 4 billion persons, a population that will have doubled, this time, in 50 years.

Economic resources, food production, manufactured articles, educa¬tion, and other necessities and niceties of life have had no such rate of gain in the countries most affected, nor is there any indication this will happen within the foreseeable future. For the world as a whole, there are just too many people. The problem is oversimplified by expressing it in terms of food supply alone. Food is a cogent consideration but clearly there is more to life than enough to eat. Favored nations have the desirable ambition to maintain standards of living reached with sacrifice and difficulty, and other millions of people in many parts of the world have the commendable urge to achieve those advantages.

The factors accounting for excess population numbers are basically ecologic. Man was equipped in the beginning with sexual drives and capacities designed for a primitive and dangerous environment. Those were the days when less than half of the children born survived to adult age. Meanwhile the environment has changed materially. In earlier days changes were slow because the means to change the basic conditions were poor. The capabilities are now much improved, with the result that progress is faster and the nature of change more pro¬found. Modern technology takes an important part in this, but no ele¬ment seemingly has more significance than medical science, operating through improved medical care, the prevention of disease, and the maintenance of health.17 The result has been a decided decline in death rates. Birth rates, for the reasons stated, tend to remain at high levels. The result is an increasing population; under some conditions, as in Ceylon, this is fantastically true and within periods as short as a decade. Such is the population dilemma.18

Population pressure, although it is close to universal, geographically manifests itself unequally in the several parts of the world, in Europe less than in Asia, and in Australia less than in South America. What¬ever the general area, centers exist where conditions are close to acute. Rates of increase are less in great cities and for the upper social classes than for rural residents and the poor. India is commonly cited as an extreme example of a country in difficulty, but actual rates of increase for that population are about the same as in the United States. Green¬land has a population of only 37,000 in an area that exceeds 800,000

square miles, and yet the annual rate of increase and the existing popula¬tion pressure is greater than in either India or Ceylon. A principle becomes evident: the difficulty is not in absolute numbers of people, nor how bad or how favorable the environment, but how the one equates with the other. The world as a whole is involved. Although some nations are in a more favorable position than others, modern communi¬cation and an interlocking economy determine a situation where the difficulties of one nation are necessarily shared by many others, and this wholly aside from any ethical idealism.

One remedy for an excess of people beyond available resources is to supplement the existing effort toward limitation of deaths, so long the driving force behind public health, by a commensurate attempt to limit births; in simple terms, birth control as well as death control. Because population pressure relates so directly to health, and because organized health agencies possess a staff, facilities, and experience suited to the task, population control is judged best delegated to that particular instrument of society.

Religious and ethical beliefs have changed materially in many cul¬tures during the past century. Environment has changed. The num¬bers of people have increased. Collectively, these events suggest the usefulness and the desirability of a change in the pattern of human reproduction and a fresh approach to understanding the nature of man.

Population control is a basic matter of health, demanding the best in medical science and health administration to permit a sound and solid attack, divorced of the prudery and prejudice and oftentimes out¬right sensationalism still associated with that endeavor. The control of alcoholism gained definiteness and precision as alcoholism came to be considered a medical problem.19 Population pressure will profit when society recognizes it as a health matter.

Population structure. The factor mainly responsible for increased numbers in the world population is a declining death rate, and that in turn has been brought about to an important extent by an improved medical technology. This iatrogenic influence also is responsible for a qualitative change in many populations, primarily in respect to age. The longer life span produces an older population. With more people beyond age 65, we find more chronic illness and more people with a physical or mental handicap. Modern antibiotics and chemotherapy

have made a singular contribution, in that the pneumonias and other infections once so largely responsible for putting an end to degenera¬tive and neoplastic disease are now far less exacting. The result is not only greater numbers of the chronically ill, but an altered character and severity of chronic illness. An advanced pathology becomes evident these days, of a kind little known in other years.

Progress in medical science, like other great technological advances, commonly results in a new set of social, economic, and political prob¬lems. The increased years of retirement, the shortened work day, and the fewer days worked per week are other associations that come with an aging population. The net effect is that workers within the produc¬tive years have an increasing number of dependents to support.

Mental disorder. That public health for many years centered its efforts on control of the communicable diseases was well justified. Whatever the country or climate, the infections were first in account¬ing for the number of persons becoming ill and for the number who died. These illnesses develop acutely, with signs and symptoms that permit ready recognition. Technical methods in control of the environ¬ment were reasonably simple and readily developed. Research added more and improved procedures. Progress in control has been outstand¬ing in highly developed countries. Even in areas with scanty resources conditions have improved greatly within recent years.

The mass diseases that originate in disturbances of metabolism and from neoplastic and degenerative processes are chronic conditions of increasing practical importance as the infections subside. They came as the next general order of business in public health. Still later and after unreasonable delay, traumatic injuries took a rightful place among pre¬ventive activities of official health agencies. This concerted emphasis on physical ills served eventually to uncover a frequency of mental disorders beyond the estimates of informed public health workers.

The mass attack on community disease by way of public health also brought method and experience by which to judge the burden of behavioral abnormality and mental sickness. Today mental illness has been given a front place among activities in epidemiology,20 with the objective of defining origin of cause and course, thereby deriving the necessary facts for control.

Mental health is a relative concept, dependent on the culture to which it relates, and that culture derives in turn from an interaction of human host and surrounding environment. Man has a nervous system that evolved originally under conditions of a simple pastoral existence, to meet the conditions of a life close to nature. During the thousands of years since then, the nervous system has experienced all manner of chance annihilation and natural selection. The necessary adaptations have brought material change in function and form.

The complexity of the modern environment is beyond anything the human nervous system was ever designed to encounter. Adaptation becomes increasingly difficult and often partial, leaving residual strains, sometimes hidden but often well evidenced in the more susceptible personalities. The modern ecologic situation thus presents an environ-ment, especially a social environment, that has measurable consequences in the pathogenesis of mass disease. Social medicine has added a new dimension to the study of disease; its usefulness is highly evident in dis¬orders of the central nervous system.

Urbanization. Aggregation in large cities has changed the way people live and the conditions to which they are subjected to such an extent that the city as an outward form and an inward pattern of life provides one of the clearer expressions of man-made disease. The existence it provides is artificial. That it has so largely supplanted a rural way of life is indicative of how far man has departed from his original nomadic habit.

Urbanization has had a favorable effect on many physical ills, through community control of waste disposal, food, water, and housing. It has exaggerated diseases associated with close contact, such as the respira¬tory infections. It has been still less fortunate in respect to emotional and mental disorders.

An urban apartment does curious things to the basic social unit, the family. Malfunction becomes still more evident in the wider relation¬ships existent in friendship circles, neighborhood institutions, and the political and social organizations of a general community. Some of the failures are found in juvenile delinquency, alcoholism, drug addiction, and a goodly roster of others. There was reason in Thoreau's retreat to Walden Pond, there to be assured of learning of nature as it really is. To this day, study of the natural history of disease through epidemi¬ological field observation finds much advantage in a rural milieu. Con-ditions there are much simplified.

A realization that the great city leaves something to be desired as a mode of life becomes increasingly evident in the growing trend toward suburban residence, which started about 50 years ago but has increased greatly since World War II. The population of the suburbs in the United States is growing at a rate more than twice that for the country as a whole. In most of New England and the Middle Atlantic states, urban population growth has virtually come to a halt, while the sur¬rounding suburbs continue to make substantial gains. Again, this eco- logic shift brings a new set of social and health problems, individual to the circumstance that brought them into being.

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL DEMANDS ON PUBLIC HEALTH

A growing appreciation that social factors are strongly involved in the causation of mass disease has had a reciprocal effect. Health mat¬ters and the professional affairs of public health are examined in turn as potential determinants of the cultural and social behavior of people.

Physicians as a profession are showing more willingness to depart from the deadly conformity of many years, a belief that a man of medicine should hold aloof from the going and ordinary affairs of the world. Clinical practice these days recognizes that medicine can not deal alone and abstractly with disease, but that the whole man enters into interpretation along with the society in which he functions.

Man as an individual cannot remain healthy in an unhealthy so¬ciety.21 These views, these attitudes, are not new. They were held by Oliver Wendell Holmes, by William Osier, and by many others of an earlier American medicine, who interpreted medical practice as some¬thing more than an applied science. Despite its broad biological base, the profession of medicine requires as well a philosophy and a social consciousness. Thus, with a changing world and a changing profession, public health comes increasingly to be understood as one of the means by which to focus social, biological, and economic resources on sig¬nificant human problems. It is thus wholly within the spirit of the times to speak of the cultural and social demands on public health as something reasonably to be expected along with the provision of sound technical services.

Foreign policy. A technical assistance program, designed to aid nations less advanced in such matters, has developed within the past two decades into a strong instrument of United States foreign policy. It takes a variety of forms, from irrigation projects and the building of dams for better agriculture, to support of industrial development, improved educational facilities, and the extension of health services. The public health part of the endeavor seemingly has an inherent advantage in expressing the fundamental philosophy of the general program. The prompt and direct impact on individual and community is such that its purpose, to promote peace and friendship among na¬tions, is seen and understood. There is the advantage that its benefits are universally appreciated by the common people, and the need is generally apparent. An innate professional pride of health workers in what they are doing, and the peculiar challenge to both native and visitor that so many of the projects provide, are other contributing factors.

International public health. Public health had come a long way by the second quarter of the 20th century, from an original concern of the local community to organization at the state and national level. Even¬tually there was recognition that the United States, along with other favored nations, had an obligation in health matters beyond domestic demands and extending to the world generally. A good neighbor policy was recognized as something more than an ethical ideal, indeed a first principle to the general preservation of life and health.

This broadening of United States health interests to include the international field began with responsibilities to Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone as the present century got under way. The increasing economic and strategic importance of the Hawaiian Islands and Alaska also contributed.

More than any other single agency, governmental or private, the Rockefeller Foundation of New York, N.Y., took leadership in intro¬ducing the United States to its obligations and opportunities in interna¬tional public health. Over the years, the work of this organization reached the boundaries of the world. Numerous other voluntary health agencies have had a part in various features of the general development.

The World Health Organization, formed after World War II, gave direction and determination to an international health effort that had run a halting course through a number of years and by way of a num¬ber of official and quasi-official agencies. The United States has pro¬vided funds and contributed technical skills to a variety of projects sponsored by this organization.

The global character of the wars of the present century has brought such an array of problems to the armed forces that military preventive medicine has experienced an unusual development. An accepted prin¬ciple in military science is that the success of troops in the field is determined greatly by assuring a healthy environment and a healthy civilian population where operations take place. Consequently, pre¬ventive medicine in the military has taken on much responsibility for public health among civilians in theaters of operation. This means an international public health, because for years our battlefields have been in other countries.

These various activities add up to an imposing total. They have been augmented recently by the new International Division of the Public Health Service. The result is a public health for export that assumes measurable proportions. The principal ingredients are money and people. Quality of staff, more than any other factor, determines the success of work in foreign fields. The contribution of the United States in this regard is of two kinds: first, through provision of educa¬tion and experience in health procedures by the country's institutions to health workers from other lands and, second, by the development of United States workers versed in health problems not ordinarily encountered in the domestic scene.

The schools of public health in the United States are meeting these obligations. During the 12 years, 1953 to 1965 inclusive, the Harvard School of Public Health graduated 986 students with professional competence in public health at the master or doctorate level. Exactly 334 were from foreign countries and, with few exceptions, they were already connected with health agencies in their own lands, to which they returned. In addition, at least 57 graduates from the United States have taken up professional activities in foreign countries. In all, about 40 per cent of graduates of these 12 years have worked overseas in public health, to which number may be added many special students not candidates for degrees.

National defense. Whether in support of foreign policy, or with altruistic intent, or from nothing more than professional curiosity about an obscure illness, a main result of international activities in public health is a contribution to the national defense. This comes through better understanding between peoples, fostered by the common en¬deavor in a problem of mutual concern. It comes also from a satisfac-tion in professional accomplishment of difficult tasks, for the health problems of less developed countries are often far from ordinary. The information derived is sometimes directly applicable to situations in the United States; under other circumstances it finds its usefulness in the country's defense needs in similar geographic areas.

Domestic health activities contribute to the national defense in more direct and evident fashion. Problems of radioactive fallout, chemical poisonings of industry, air pollution, and modern measures for the control of epidemics are features of civilian public health that relate clearly to national defense in terms of biologic and chemical warfare.

Perhaps the greatest of a country's natural resources is a healthy population, both civilian and military. A trained public health per¬sonnel is essential to this end, in mobilization, in the conduct of mili¬tary activities, and in the protection of civilian populations against the special hazards of warfare.

A FUTURE PUBLIC HEALTH

Public health today appears overly enchanted with a concept of prevention in its initial absolute sense. The situation is not altogether surprising, for that doctrine has been preached for years in the strug¬gle for acceptance of the principle that there is more to medical prac¬tice than the clinical management of sick persons. Preventive medicine for the individual extends beyond the primary endeavor of health promotion and specific protection by immunization or chemopro- phylaxis. Community disease control is also productive, short of eradi¬cation, and far more realistic, however desirable and laudable that predicated goal may be.

It is well to recognize that prevention, like medical care, is relative. In support of this I cherish the tale of the New Englander who, after a lifetime in that estimable environment, found himself unexpectedly transplanted to strange and unfamiliar surroundings in Arizona. An early thought was of health hazards. He consulted his newly found family physician, and to an eventual inquiry about the local death rate had the illuminating answer, "One per person."

Prevention in its modern interpretation by Leavell and Clark22 functions at five levels. The direct and primary objectives are health promotion and specific prevention; they continue into restriction of manifest disease through early diagnosis and treatment, to limitation of disability, and to rehabilitation of persisting defect. These principles traditionally have guided practice in the broader enterprise of control of community disease, where medical care of patient and associated family members is regularly a strong feature among measures more strictly preventive. In both activities, prevention and medical care are complementary; neither is complete within itself and neither is mutually exclusive. So conceived, prevention and medical care are coordinate elements within a practice of medicine; and public health and clinical medicine are parts of a single endeavor.

Success in prevention and control has been generally so great with the infectious diseases transmissible from person to person that for some selected few the goal has been narrowed to eradication, an objec¬tive yet to be advocated for a chronic degenerative disease, a nutri¬tional disorder, or accidental traumatic injury.23 Large areas and some¬times whole countries have been cleared of a communicable disease for appreciable periods, which constitutes excellent control and is a commendable and praiseworthy result. Eradication is not achieved until the possibility no longer exists of recurrence or reinvasion of the infectious agent in the same or altered form, an accomplishment requiring world extinction of the particular species. That has been accomplished for no disease of man; it is in conflict with ecologic theory, and is yet to be proved practical within limits of economic and professional resources. Whether public health in its present devel¬opment is served best by concentrated effort on a few diseases of diminishing significance or by attention to the broad problems of disease and injury in man is questionable.

Sources of new knowledge. A striking characteristic of public health in the United States during the past half century has been the progressive movement from concern with purely medical problems of health to the sociomedical questions inherent in human welfare. Public health presently is developing at both of these extremes, which enlarges the need for new knowledge to correct, replace, or expand the existing framework of operational health procedures.

Before natural history grew up into biology, the student of plants and animals, in this endeavor, went to the field to observe. Now for the most part he goes to the laboratory to experiment. An emphasis on the laboratory sciences as a useful source of new knowledge in prevention began with bacteriology and the communicable diseases.

Laboratory methods have proved equally productive with the newer problems of air pollution, ionizing radiation, and many others, even accidental injuries. Biophysics sometimes substitutes for nutrition or microbiology but the usefulness of laboratory procedures in defining method and approach is just as evident. Many questions are interlock¬ing, for example susceptibility to infection as influenced by radiation. The gains have been great, and yet something valuable has been lost in the transition. The contributions from field investigation24 continue to be no less significant in the problems of nature.

At the other extreme of health activities is the expanding social organization of what were once primarily medical functions. New professions have entered public health, particularly those of the social sciences. They have demonstrated their usefulness; they have broad¬ened the field of activities within public health. The value of field study further increases as social components achieve their places in an understanding of health and disease. People are not to be judged other than in relation to the environment in which they function.

Prevention for the individual. The changing character of public health effort, biologic on the one hand, sociologic on the other, is all to the good except for the gap that is left in the middle, a gap that may be characterized as the adequate provision of preventive services to the individual. More and more, public health comes to deal with groups and categories of a population, rather than with individuals in series, which is probably the main distinguishing difference between public health and preventive medicine.

An attention to the individual and his particular needs becomes increasingly necessary as emphasis shifts from the communicable dis¬eases to degenerative and neoplastic processes. The chronic diseases are less adequately served by group effort, and for a number of reasons.

Considering the progress made and the present status of prevention and control, the persons most demanding of public health attention in the United States are today males of 45 to 64 years. Tuberculosis has a stronghold there. The principal diseases are of degenerative and neoplastic origin. They could profit from the principle so well estab¬lished for tuberculosis, that no malady has ever been controlled by an attempt to cure all affected persons. True enough, these chronic diseases are usually first manifest at the older ages, and treatment necessarily begins there, but the place to center preventive activities

is when they really begin, which is much earlier.

There is biologic evidence that senescence begins in fetal life, before birth. A practical time for serious attention to preventive meas¬ures against chronic disease generally is at 25 years, an age marking stabilization of the resting heart rate at 70 per minute, the end of growth, and the peak of physical maturity. For some conditions the basic approach is still earlier, notably obesity, atherosclerosis, and others. The repeated illnesses and injuries in childhood and during the years of an active working life rarely end in complete compensation. Some level of dysfunction is to be expected, sometimes temporary, occasionally permanent, and commonly additive. The composite of such events provides the pattern of causality for the degenerative diseases of old age.

The present public health approach to chronic disease begins too late. It is too widely separated from clinical practice and the problems of the individual, so much so as to suggest that medical care and prevention are independent activities. Too many professional disci¬plines, some medical, some sociological, and some psychological, have come to view the problems of old age as their own particular province, even to the extent of warning poachers away.

The need is to bring biological and sociological effort into a com¬mon endeavor. The dichotomy is still too evident. Progress is being made, but something more is needed than exhortation or even reason. The logic provided by a unifying scientific discipline is seemingly the answer. Evidence has been introduced12 that human ecology has the capacity to meet that need.

The atomic age has had its effect on public health method and thought, along with many other impacts on world society. For many years the population of the United States has come to look upon preventive health services as something to be provided for them, rather than by them. This reaches beyond the basic considerations of sick¬ness and injury, to include patterns of growth and development, gen¬eral well-being, and physical safety. Society has led man to expect as an inherent right the necessary materials for health maintenance, in requisite amounts, delivered when he needs them, and in the manner he prefers.

Gradually, we are realizing that we now face a different kind of world. This has been recognized by the military, who emphasize for the individual an education on how to provide his own preventive measures; they also teach small groups how to maintain themselves independently, in contrast to the former concept that such respon¬sibility rests with the military community, acting through command.

The civilian likewise faces the possibility of atomic disaster and situations where, cut off from his antibiotics and his customary com¬munity health protection, he must depend on his own resources for survival. Such demands require a new kind of health education. One practical development is the community homemaker service, which has the objective of helping families to maintain themselves at home when illness or other major crisis occurs.

Specifically directed effort. The era of the antibiotics has had the further and indirect effect of strengthening a specific approach to the solution of public health problems. Gradually the place of epidem¬iology as the diagnostic discipline of public health becomes firmly fixed. Epidemiology has always operated on a theory of causation that public health practice follows, for it is the corollary of treatment in clinical management.

Even as late as 1850, public health administration had progressed little past that of the early Greeks, who laid emphasis on gymnastics, heliotheraphy, massage, baths, and diet. Then came the great sanitary awakening and the tendency to try every plausible control measure on the assumption that, fractionally, the result might have value.

The past few decades have seen a strong turn toward specific attacks on individual diseases, and more particularly on specially identi¬fied health situations, in place of indiscriminate general effort. The contribution of epidemiology has been through emphasis on specific causation, no longer restricted to an agent of disease but instead to the constellation of factors responsible for a prescribed difficulty. The result has been a broad change in administrative action: from police power as the main reliance in the days of environmental sanitation to the health education of today, now the driving force in implementa¬tion of epidemiologic principles.

SUMMARY

The public health of a century ago was concerned chiefly with environmental sanitation and the control of the communicable dis¬eases, problems that had their origin in the physical and biological environment. Police power was the usual means of accomplishing prevention and control. Progress in method and procedure was mainly through improved technical skills and common sense. Organized scien¬tific research was yet to come.

The health activities of today relate principally to the chronic diseases of degenerative, metabolic, and neoplastic nature, brought into prominence by an aging population and a lesser frequency of infection. A changing technology in industry, a developing ionizing radiation, and a mounting volume of mental and emotional illness make for a health program more diverse and complicated than in former years.

The mass disease of today in the United States and similar indus¬trialized nations is mainly man-made. Its causes rest profoundly in host characteristics and the social environment, in strong contrast to the free natural origin of former years and the situation presently prevailing in less developed regions. Health education and community cooperation substitute for police power in the practical accomplish¬ment of prevention and control, the emphasis being on help and advice instead of legal compulsion. Skills in human relations acquire impor¬tance in the modern practice of public health as a means of getting people to do things, and the advances in professional and technical procedure have a solid grounding in scientific research.

These new conditions measurably alter the approach to prevention and control. The mass measures that served so well when the main problem was water supply and an epidemic of typhoid fever are not as well suited to the chronic and endemic diseases of the present. A more individualized prevention is suggestively more productive, with rhe important added element that active cooperation of the person concerned comes close to being essential. An atomic age, a more com¬plicated society, a peripatetic population, brings the potential of situa¬tions where the individual can no longer depend wholly upon society to provide preventive protection, but must possess the knowledge and means to fend for himself when circumstances so require.

The conclusion would be that the practice of the future must place increasing reliance on preventive medicine for the individual, complementing the mass measures for community protection, which is the classical public health.

[REFERENCES ON FOLLOWING PAGE]

REFERENCES

1. Report of the American Public Health Association Task Force, Arden House Conference, October 12-15, 1956, Amer. J. Pub. Health ^7:218, 1957.

2. Rosen, G. A History of Public Health. New York, M.D. Publications, 1958.

3. Duffy, J. Epidemics in Colonial Amer¬ica. Baton Rouge, Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1953.

4. Gallup, J. A. Sketches of Epidemic Dis¬eases in the State of Vermont. Boston, Bradford and Read, 1815.

5. Webster, N. A Brief History of Epi¬demics and Pestilential Diseases, 2 vols. Hartford, Hudson and Goodwin, 1799.

6. Smillie, W. G. Public Health: Its Prom¬ise for the Future. New York, Mac- millan, 1955.

7. Chapin, C. V. History of state and municipal control of disease. In: A Half Century of Public Health. Ravenel, M. P., ed. New York, Amer. Public Health Ass., 1921.

8. Blake, J. B. Public Health in the Town of Boston, 1630-1822. Cambridge, Har¬vard Univ. Press, 1959.

9. Bolduan, C. F. Public health in New York City, Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 19: 423, 1943.

[0. Winslow, C.-E. A., Smillie, W. G., Doull, J. A. and Gordon, J. E. The History of American Epidemiology. St. Louis, Mosby, 1952. [1. Terris, M., ed. Ooldberger on Pellagra. Baton Rouge, Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1964. 12. U.S. Government Organization Manual 1958-59. Federal Register Division, U.S. National Archives and Records Service. Washington, D.C., Govt. Print. Off. 1958.

L3. Sources for these and other cited vital statistics include: a) statistical bulletins of the Metropolitan Life Insurance

Company, New York, N.Y.; b) a va¬riety of reports from the Public Health Service, Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, Ga.; c) annual reports of the Depart¬ment of Public Health of the Common¬wealth of Massachusetts; and d) the Demographic Yearbooks published by the United Nations in New York, N.Y.

14. Gordon, J. E. Medical ecology and the public health, Amer. J. Med. Sci. 235: 337, 1958.

15. Rogers, E. S. Human Ecology and. Health, an Introduction for Adminis-trators. New York, Macmillan, 1960.

16. Dubos, R. Man Adapting. New Haven and London, Yale Univ. Press, 1965.

17. Gordon, J. E., Wyon, J. B. and Ingalls, T. H. Public health as a demographic influence, Amer. J. Med. Sci. 227:326, 1954.

18. Osborn, F. H. Population: An Interna¬tional Dilemma. New York, Population Council, 1958.

19. Kruse, H. D. Alcoholism as a Medical Problem. New York, Hoeber-Harper, 1956.

20. Plunkett, R. J. and Gordon, J. E. Epi-demiology and Mental Illness. New York, Basic Books, 1960.

21. James, G. Poverty and public health: New outlooks. I. Poverty as an obstacle to health progress in our cities, Amer. J. Pub. Health 55:1757, 1965.

22. Leavell, H. R. and Clark, E. G. Pre¬ventive Medicine for the Doctor in His Community: An Epidemiologic Ap¬proach, chap. 2. New York, McGraw- Hill, 1958.

23. Gordon, J. E. Communicable disease control: Old principles in a new setting, Amer. J. Med. Sci. 250:3^6, 1965.

24. Gordon, J. E. Field epidemiology, Amer. J. Med. Sci. 246:354, 1963.