Of all the French Impressionists, Edgar Degas is generally viewed as the most conservative. Unlike Monet and the rest of the clan, who set up their easels in the verdant out-of-doors and recorded the fleeting effects of light, Degas preferred the grand indoors.

Trained in academic drawing, he was one of the great draftsmen of the 19th century and he never abandoned his love of the figure. Today, his female figures can induce mixed feelings. His bathers, with their gauche poses, look a little bovine as they climb into tubs and at time suggest a disturbing voyeurism on his part.

[Click on “Listen” for Solomon’s review of the show with WNYC’s Richard Hake.]

Yet “Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty,” a breathtaking show at the Museum of Modern Art, argues that the artist was far more modern and experimental than his reputation suggests. The exhibition focuses on his monotypes, a lesser-seen aspect of his production that enabled him to be loose and free.

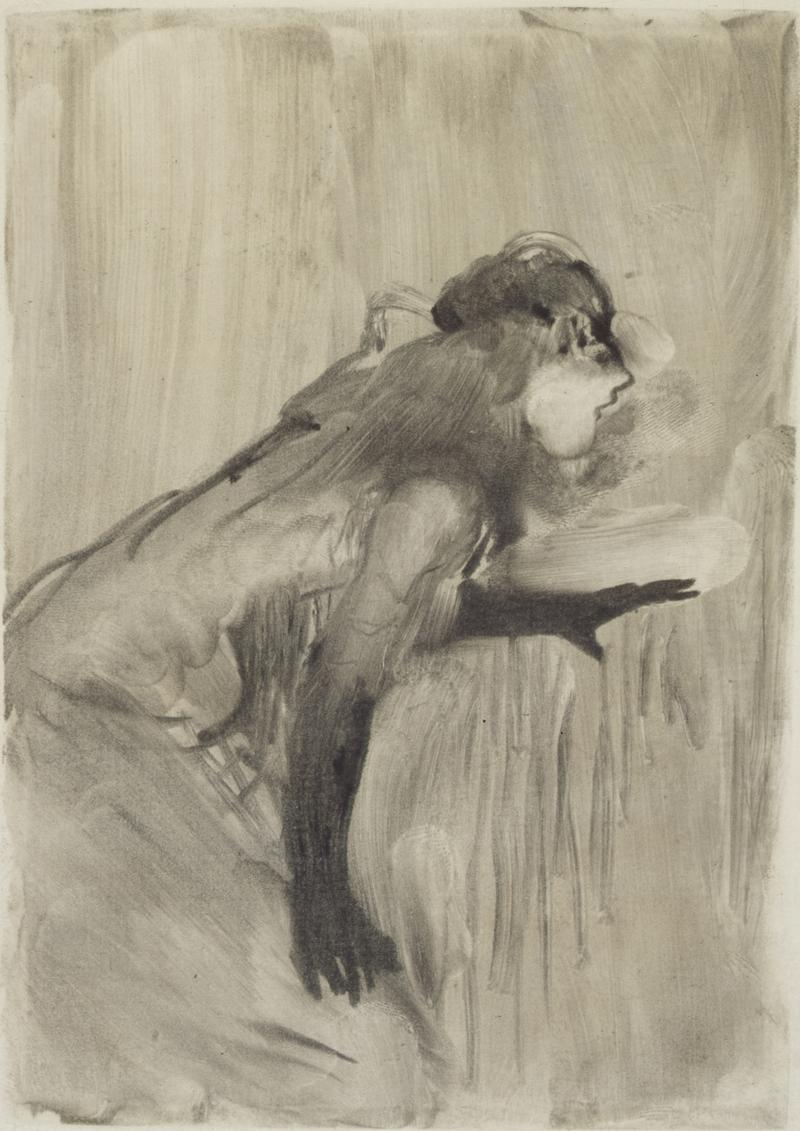

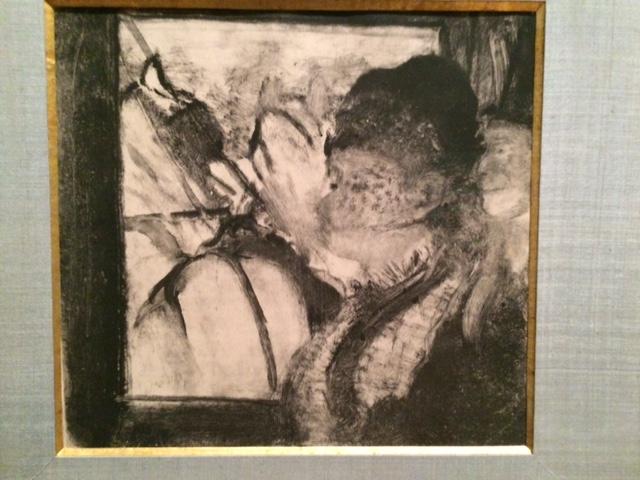

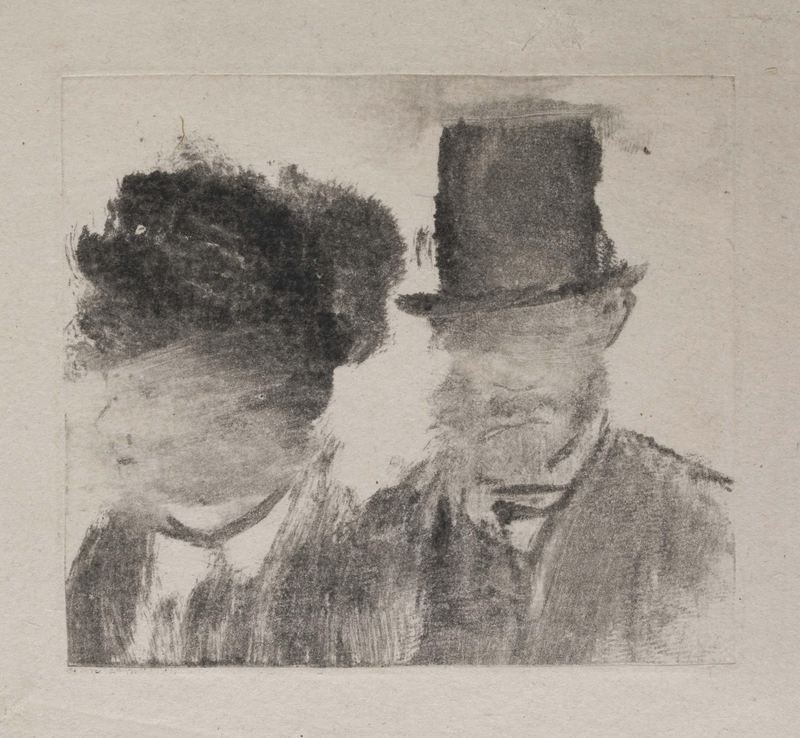

A monotype, technically, is a relatively simple process that yields up a single print (as opposed to an edition). More often than not, it begins with a pot of greasy printer’s ink and a smooth metal plate on which to draw. Most of the monotypes in the show are small in size, and allow us to watch Degas create streaks of light and shadow out of the muck of viscous black ink. He often applied the ink, or wiped it away, directly with his hands and left fingerprints as evidence. My favorite piece in the show, “In the Omnibus”— in which a woman with a veiled hat is shown in profile, riding a bus — is a marvel of economy, a welter of dark smudges and smears that somehow coheres into a graceful portrait.

After printing an image, Degas would often run the plate through the press again, creating a second print, a ghost image of the first. Its very paleness provided him with an invitation and an excuse to colorize the image by adding some pastel. There are visual pleasures here that you will never see anywhere else, as you watch Degas rework his images —repeating them, reversing them, mirroring them, pastel-izing them. The variations hint at his obsession with “process,” one of the key concepts of modern art. By a nice coincidence, Jasper Johns, a more recent master of the monotype, is having a show devoted exclusively to some 40 years of work in that medium at the Matthew Marks Gallery, starting May 6. This is, happily, the spring of the monotype.

Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty at MoMA runs from March 26, 2016 to July 24, 2016.