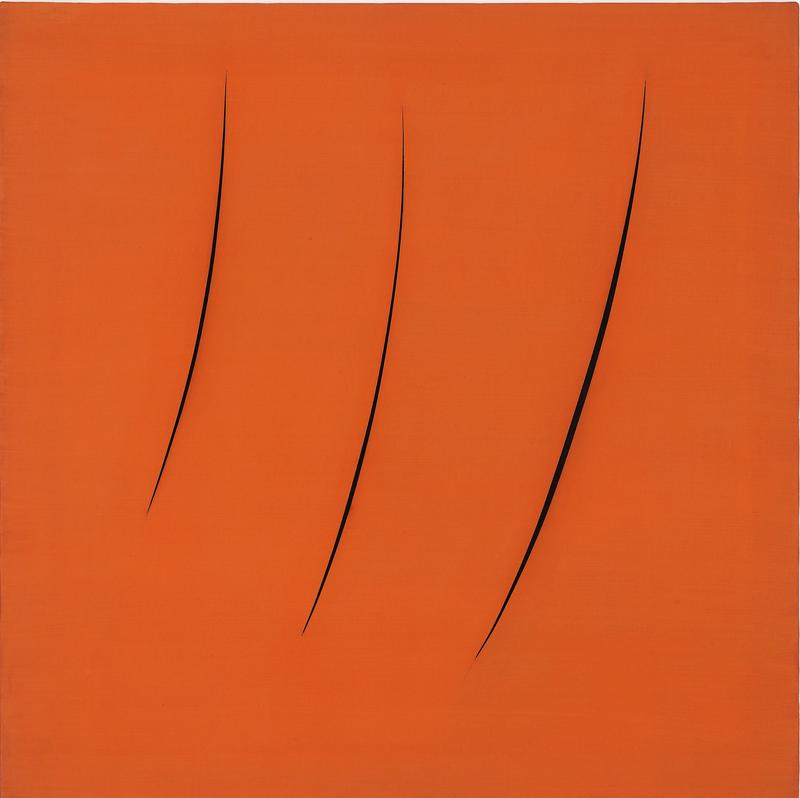

Lucio Fontana, an Argentinian-born artist who spent most of his life in Italy, is known mainly for one thing. His so-called Cut Paintings are easy to recognize. They typically consist of a bright surface of flat, uninflected color that has been slashed vertically with a knife. The incisions are narrow and rather tasteful, but as visually disruptive as a scar running down one’s midriff.

It has never been clear whether Fontana – who died in 1968, at the age of 69 – should be remembered as a daring exponent of the avant-garde, or an artist whose work calcified into cliché. Of course it is possible to be both at once, and “Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold,” a handsome if flawed retrospective at the Met Breuer, showcases both the good and the less good. I don’t love the Cut paintings, in part because the artist’s stated intentions seem so unconnected to the results. He spoke of his work as an exercise in “spatialism,” i.e., expanding art into empty space, yet the paintings generate very different associations (from slit-open envelopes to the act of self-mutilation) and suggest that Fontana was not in control of the metaphoric meaning spawned by his work.

The climax of the Met show comes long before the Cuts. The opening gallery fascinates. It is filled with a riotous assembly of predominantly ceramic sculptures, from comely female heads to impressively lumpy abstract forms inspired by sea creatures; much of this work remains unknown in New York. Born in Argentina, in 1899, the son of a traditional sculptor who specialized in funerary monuments, Fontana began his career as a sculptor, and one senses in the early work both an affection for materials and an opposing desire to be free of them, to float weightlessly.

He can remind you of another modernist sculptor-painter, Alexander Calder. Fontana and Calder were almost exact contemporaries. Both were the sons of sculptors who worked in a conservative style, turning out figurative monuments that had a clear sense of civic purpose. Compared to their fathers, Fontana and Calder qualify as the most rascally avant-gardists, dispensing with the heaviness of the past in favor of light-as-air gestures.

Fontana was a ceaseless experimenter, but one problem with the Met show is that if fails to contextualize his work. For instance, were his pioneering shaped canvases seen and appreciated by such American purveyors of the shaped canvases as Frank Stella or Ellsworth Kelly? Astoundingly, neither Stella nor Kelly is mentioned in the exhibition catalogue. Nor are Dan Flavin and Bruce Nauman, American sculptors who, coincidentally or not, echoed certain of Fontana’s innovations (which included a taste for neon tubing and walk-in installations). It’s unclear in what direction the influences flowed – and also possible that there was no influence at all between Fontana and the Americans. Nonetheless, it would be helpful to know, and until then, Fontana will seem more like an entertaining Italian novelty than an essential part of modernist culture.