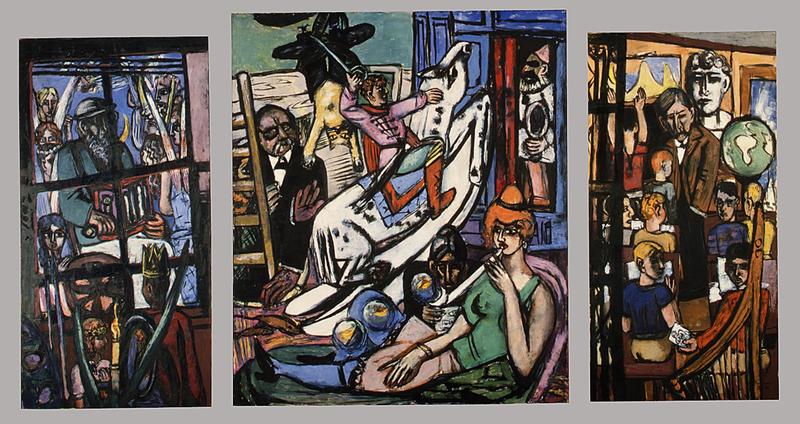

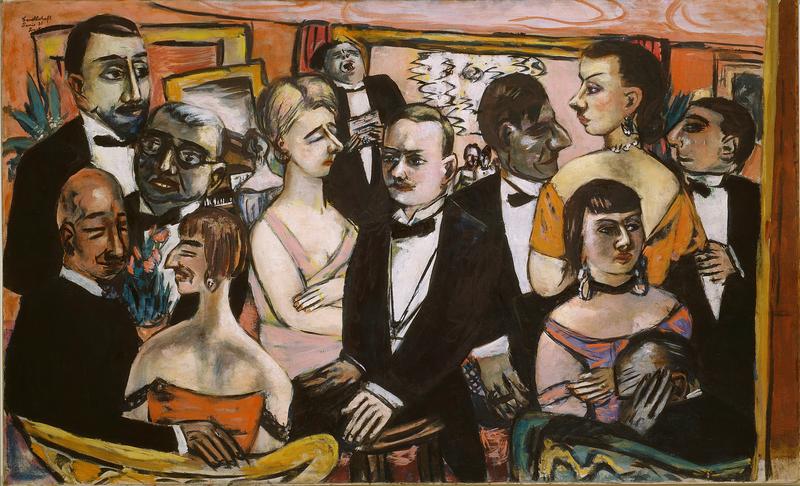

Max Beckmann was, by any measure, the greatest German artist of the 20th century. Yet he has never had the allure of his European compatriots Picasso and Matisse, perhaps because he was never a crusading modernist. In the heyday of abstract painting, he clung to the hidebound tradition of figure painting. And while other painters banished story-telling from their canvases in the interest of radical reduction, Beckman went the opposite way, loading up his pictures with burlesque dancers and medieval kings, with banjo-players and sword-wielding soldiers, mingling the sights of the present with characters out of the Bible or mythology and striving for high drama.

“Max Beckmann in New York,’” the beautiful show that curator Sabine Rewald has assembled at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a partial retrospective, which might sound like a contradiction of terms. It brings together two distinct bodies of work – the paintings that Beckmann did during his brief, late-life stay in New York City, and earlier paintings that happen to be owned by New York private collectors or institutions. This is a risky approach, since its organizing principle owes less to the merits of individual paintings than to the randomness of their owners’ addresses. But somehow it works, perhaps because Beckmann is so inherently compelling. A refugee from Hitler’s Germany, which classified all modern art as criminally degenerate, he and his wife arrived in the States in 1947. They eventually settled in an apartment at 38 West 69th Street, off Central Park West. In 1950, at age 66, he suffered a heart attack while walking to the Met. The circumstances of his death have been cited as the inspiration for the current show.

You can also see the show as a form of curatorial atonement. In 1971, Henry Geldzahler, the museum’s brilliant curator of contemporary art, made the astonishingly poor decision to de-accession three of the Beckmanns in the Met’s collection. He was trying to raise money to buy a David Smith sculpture. Fair enough. But among the sacrifices was Beckmann’s “Self-Portrait with Cigarette,” an intense, magnetic painting that wound up in Germany, but is back in New York for the current show. It’s a knock-out, an unfiltered portrait of a middle-aged man with a boulder of head, heavy black outlines everywhere, his green scarf and blue jacket as radiant as shards of color in a stained-glass window.

It’s unsettling to think about the vicissitudes of taste. Beckmann was deemed irrelevant to the history of art as recently as 1971. In fact, it wasn’t until a new generation of Neo-Expressionists (Georg Baselitz and company) emerged in the 1980s that Beckmann was rehabilitated as a master. You assume his reputation is safe from hereon in. But Beckmann, who spent his life in flight from the forces of evil, knew that no one and nothing is ever permanently safe. So let’s not take this current moment of Beckmann appreciation for granted.