Everyone interested in art history knows about the Bauhaus, the adventuresome school in Weimar, Germany, that put crafts on equal footing with high art. But inevitably you are less familiar with “The People’s Art School,” a similarly progressive academy that was founded in the snowy provinces of Vitebsk, Russia, in 1918, just a few months before the Bauhaus. The Vitebsk school is now the subject of a fascinating group show at the Jewish Museum that brings together the work of about a dozen of its faculty and students. The three best-known among them are mentioned in the title – an act of snobbism that flies in the face of the collectivist beliefs explored by the show.

No matter. “Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-22” offers a deeply satisfying introduction to an overlooked moment in art history. In 1918, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, Marc Chagall became head of the brand-new, tuition-free People’s Art School in his native Vitebsk. It was a triumphant period for Chagall, not least because the Revolution granted full-fledged citizenship to Russian Jews for the first time. His eight-foot-tall painting, “Double Portrait with Wine Glass” – in which the artist sits astride his wife’s shoulders, raising a glass – looks almost tipsy with optimism.

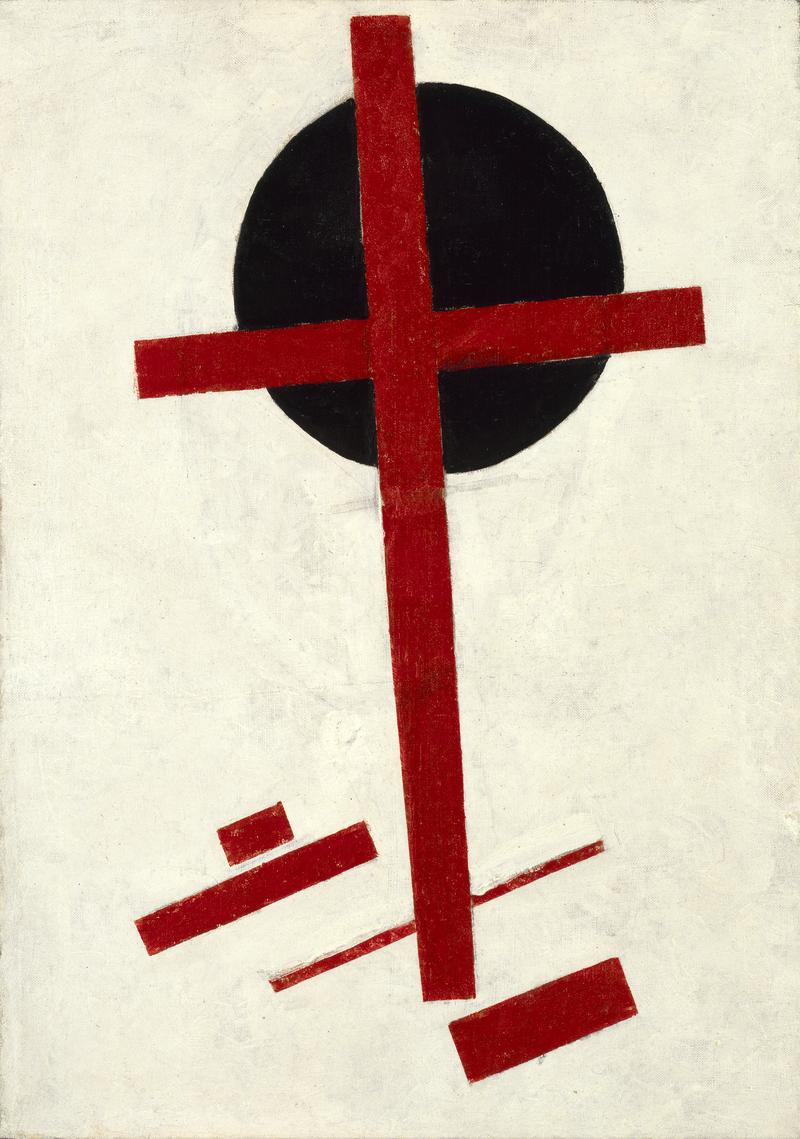

A year after the opening of the school, Kazimir Malevich arrived and joined the faculty. He quickly became Chagall’s nemesis. While Chagall painted poetic scenes of his hometown – with cows and goats and upside down houses – Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, demanded that realistic subject matter be jettisoned from art. His paintings, with their airy arrangements of crosses and rectangles rendered in stark red and black, have the look of revolt, and students immediately signed on. To Chagall’s dismay, his own students abandoned him, quickly switching to Malevich’s class and the vogue for geometric abstraction. Chagall resigned from the school and moved away from Vitebsk.

Not all of the work in the Jewish Museum show is first-rate, but it’s not intended to be. Instead, it evocatively captures one of those rare moments in history when art fervor blended with political fervor. How best to capture it? The other day I watched “Chagall-Malevich,” a Russian film that came out in 2014, and is available online. As far as period dramas go, it’s a bit heavy-handed, but it includes some wonderful scenes of the cobblestone streets of Vitebsk festooned with Suprematist-style posters, banners and trolley car decorations. They’re a poignant reminder that the People’s Art School began as a utopian project, but produced only one graduating class. Sadly, it resembles the Bauhaus not only in its early idealism, but in its tragic defeat by the forces of fascism.