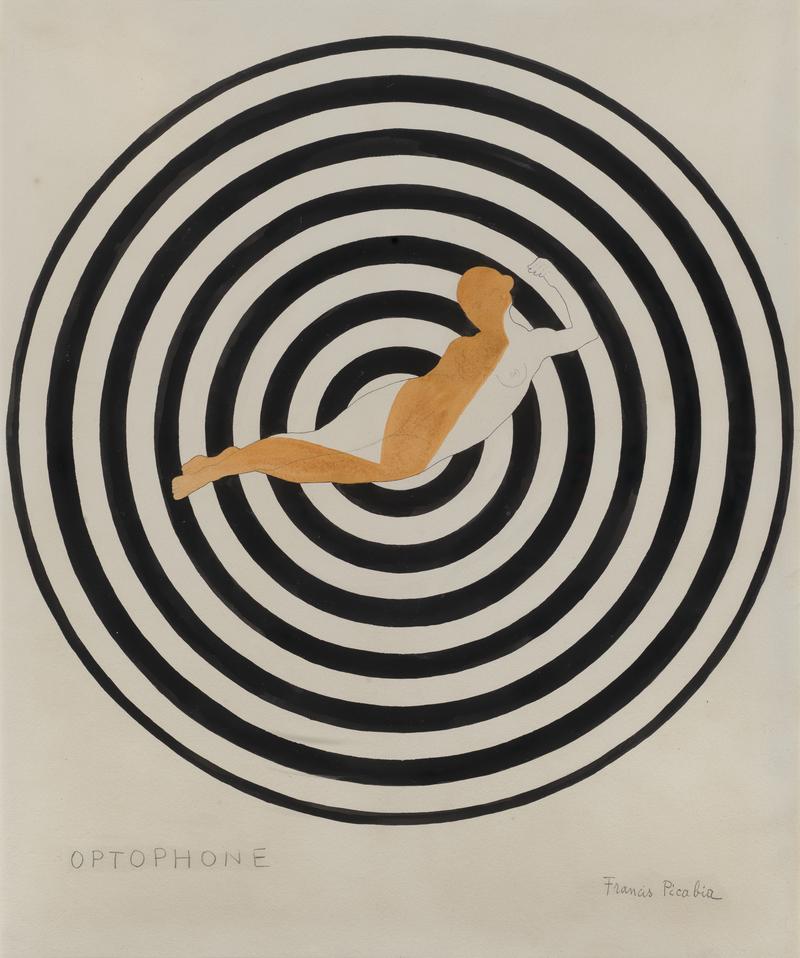

Francis Picabia’s career has long been split into opposing halves. He was one of the founders of the Dada movement in the years following World War I, and his early paintings and drawings were dutifully experimental. A natural draftsman and quick study, he mastered the workings of Impressionism and Cubism before turning out his witty “Mechanomorphs” – paintings of fantasy machines whose pistons and cylinders can be read as male and female body parts coming together in eternal overtime.

Picabia’s later work, by contrast, was once viewed as a retreat into old-hat realism. Critics wrote it off as clumsy, at best. Yet today we can say it speaks to the moment.

The highpoint of the massive retrospective of his work opening on Monday at the Museum of Modern Art comes in the rooms devoted to Picabia’s so-called “Transparencies,” which superimpose unrelated images on top of each other like so many see-through veils.

In a mural-size painting such as “Melibee,” of 1930, a tender-eyed Madonna lifted from a Renaissance painting gazes through a tangle of branches and asterisk-like stars, there but not there. The poetic layering can put you in mind of David Salle and other living artists who mix and match images that don’t belong together, and convey a sense of the unanchored, floating-away feeling of contemporary life.

As a personality, Picabia left much to be desired. In most accounts, he comes across as a cavalier playboy. Born into an affluent family in Paris, in 1879, he spent much of his adulthood in Cannes, assembling a sizable collection of racing cars and yachts.

During World War II, when many of his artist-friends sailed to New York and sit out the war, Picabia lingered on the French Riviera and made his peace with the Vichy regime. After it collapsed, Picabia was arrested by French officials for being a Nazi collaborator, although the charges were eventually dropped.

Is all this relevant? By now we know better than to judge an artist by his or politics or ethical failings. Yet the problem with Picabia is that his art, too, seems driven by convenience and a lack of rigor. He had no interest in form – in breaking it down and reassembling it, as Picasso did – and treated art styles as if they were so many sleek cars to be raced and discarded. To be sure, there are many beautiful paintings in the show, especially among the “Transparencies,” and I suspect that contemporary artists of all persuasions will find isolated works to admire. But, taken as a whole, Picabia is not a deep enough artist to justify a show of this size. Perhaps I am merely suffering from post-election blues, but at a time when our politics are plagued by so much dishonesty, Picabia’s slipperiness and moral ambiguity make him hard to admire.