Stuart Davis, who was born in in 1892, the son of two artists, was an appealing figure. In the 1920s, when New York was still regarded as a cultural backwater compared to Paris, he set about to improve the situation – to Americanize modernism and to modernize America.

[Click on “Listen” for Solomon’s review of the show with WNYC’s Soterios Johnson.]

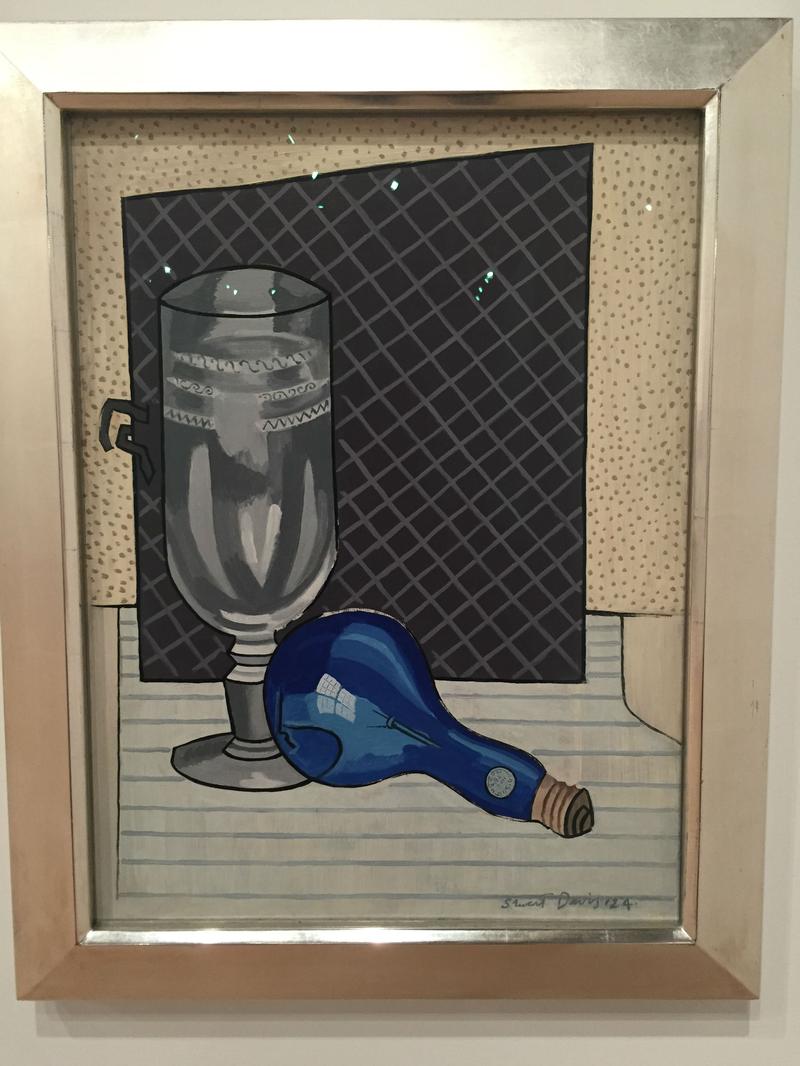

He actually succeeded, to judge from “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing,” a sparkling retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the first gallery of the show, his “Edison Mazda” (1924), with its 75-watt, blue-hued light bulb, injects a comic note of consumerism into the tradition of the Cubist still life. New kitchen appliances, which drove the advertising industry in the 1920s, materialize here as well. Paintings such as the amusing “Super Table” – a futuristic oven, bar and table combined in one – have a cartoony bounce that can put you in mind of both Wilma Flintstone and Philip Guston’s figurative paintings from the ‘60s.

The key word here is forerunner. Davis glamorized everyday objects long before Warhol apotheosized Campbell’s soup cans. And Davis’s graphic clarity, his legibility, his screaming juxtapositions of undiluted primary colors, look forward to Roy Lichtenstein’s crisp universe.

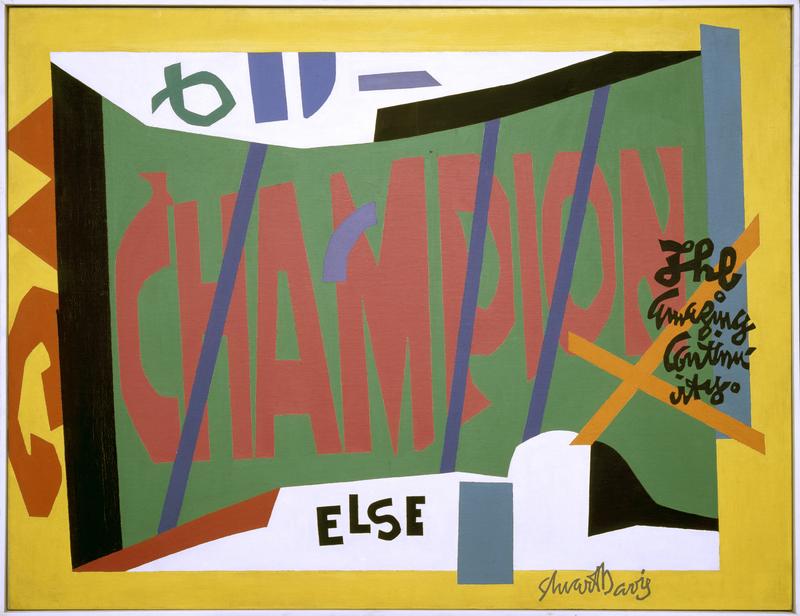

The Whitney show emphasizes Davis’s later work – that is to say, the paintings of his artistic maturity in the 1940s and 1950s, when his forms became flatter and bolder and almost totally abstract, like the collaged paper scraps in a Matisse cut-out. In the early ‘50s, he lifted the word “Champion” from a matchbox ad for spark plugs and splashed it across a series of canvases circa 1950, a witty tribute to the stature of American art after World War II.

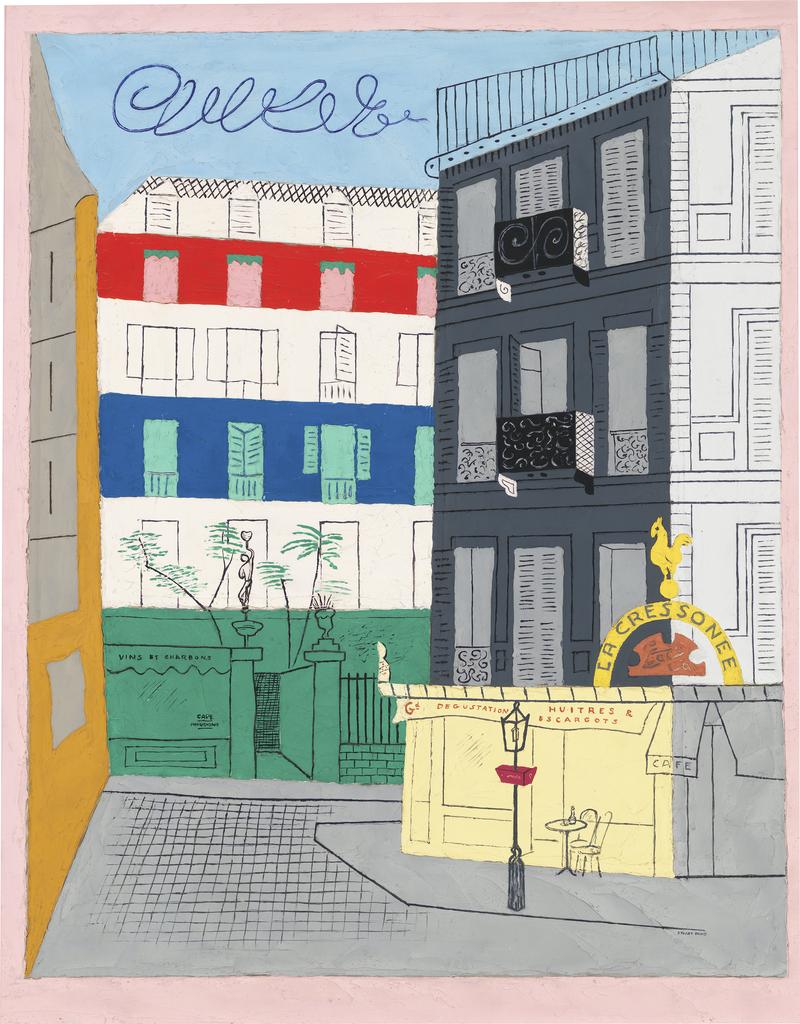

Still, at the risk of heresy, I prefer the earlier work, the pre-abstract works, when his lines were wobbly rather than ruler-straight and his colors came in candied pinks and blues. I love his streetscapes from Paris in 1928, impossibly charming scenes that render building facades as slabs of pastel color while leaving room for such quirky details as a curling wrought-irony balcony, or a blue seltzer bottle resting on a ledge.

All in all, his work is singularly accessible and wholesome. You can say it took the sex out of Cubism. In the place of sensuality, it offered a shout-out to the so-called American spirit, with all that implies about optimism and energy. His work seems free of angst or introspection, which is perhaps why it feels less urgent than that of Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe and his other colleagues in the first wave of American modernism.