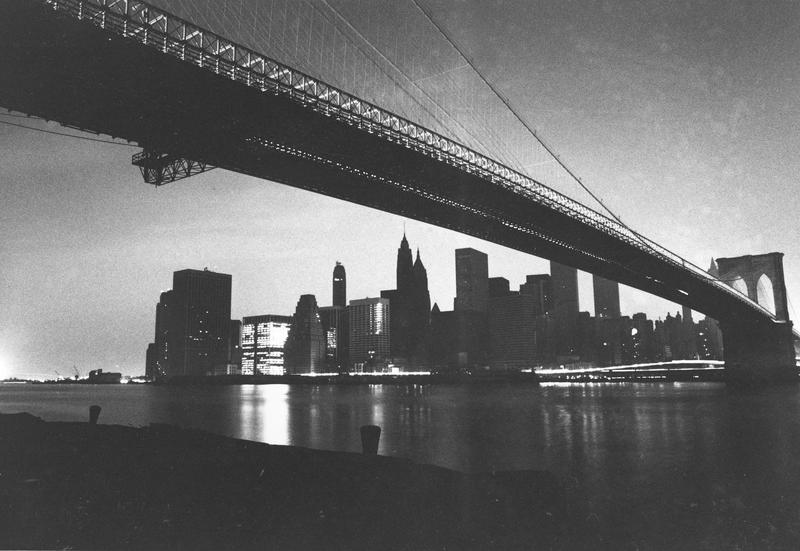

Revisiting the 1977 New York City Blackout

( Ray Stubblebine / Associated Press )

Filmmaker Sam Pollard revisits the New York City blackout of 1977, the subject of a new documentary he's working on. Plus, listeners offer their oral histories.

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Now, we're going to do an oral history call-in to help director Sam Pollard with the documentary he's making about the New York City blackout of 1977. It was July 13th, a very hot day like today. The high was in the 90s. I'll tell my own blackout story as part of this and we'll invite yours for those of you who were alive yet, experienced it, and remember something meaningful about it, but let's bring Sam right on to explain the project and why he wants your stories.

Sam Pollard, as many of you know, is a historian and filmmaker, collaborator with Spike Lee on films such as When the Levees Broke about Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and 4 Little Girls about the 1963 Birmingham Church bombing. He's an Emmy winner, a Peabody winner, an Oscar nominee, and so much more. He was last on this show around Juneteenth last year for his documentary about the jazz drummer, Max Roach. Sam, always an honor to have you on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Sam Pollard: My pleasure, Brian. Good talking to you.

Brian Lehrer: Set this up for us. Why are you making the film now about the blackout of 1977?

Sam Pollard: These two filmmakers from England reached out to me a few months back. They were interested in doing a documentary that looked at the blackout in 1977. I got very enthusiastic because I was around and I was in that blackout when it happened in '77. It really piqued my interest and we started doing some research. We're looking to find people who can tell us their stories through audio or photos or even the footage about their experiences that night.

I remember I was over on 49th Street and Broadway. I was working on the film as an assistant editor. The whole editing space went completely black. We crawled down the stairwell from the ninth floor to the streets. At that time, I lived in the Bronx. I was trying to figure out how to get back to the Bronx. I'm walking east and somebody had thrown out a vat of tomato sauce on the street, which I didn't notice.

I completely slipped and fell in this tomato sauce. [chuckles] I was full of tomato sauce as I'm inching east. I was able to find, back then, as you know, a gypsy cab that took me all the way to Soundview in the Bronx. I had to walk up another 12 flights to get to my apartment. I had just gotten married and I was only 27 years old. It was some night that I remember. What's your story, Brian?

Brian Lehrer: Before there were Ubers, there were gypsy cabs. I'll tell my story in a sec. I want to just get the phones going because I know this is what you want. Because unlike other times when you've come on with a documentary you had already made, you wanted to come on today while you're still making this one. How can our listeners help?

Sam Pollard: Well, if they can just reach out to us and give us their phone numbers or email addresses, we're looking for people who had some unusual, unique experience that night where they had some party. Were they with friends? Did friends come over? I was talking to someone the other night who said that they had 22 people living in their apartment that night because they couldn't get home. They couldn't figure out how to get home.

We've already found people who were working on the Superman film with Chris Reeves. We found a store owner who lost everything and looters helped themselves to his store. We're looking for all these kinds of stories to round it out. We know there's great archival footage from ABC and CBS and NBC and the local stations at that time, WPIX and WOR, but we're looking for these real, very specific personal stories that can help round out and shape the arc of this documentary.

Brian Lehrer: A lot of people have these memories because our 10 lines are already full. We will go to the phones in just a minute, but you asked for my story. It's funny because I didn't know your story started on 49th Street. Mine actually ends on 49th Street. Where does it start? I was in CBGBs that night.

Sam Pollard: No.

Brian Lehrer: No kidding. The Lower East Side rock and punk club for people who don't know it. My brother and I and our girlfriends at the time went to see a band called The Shirts, who I was into. The music hadn't started yet. The club like many music clubs was dimly lit for a chill atmosphere. As I remember it, there were candles on the tables. For the customers like us, that was the lighting.

I imagine for the workers behind the bar and elsewhere, there was more lighting, more electricity for them to see go out. For us, it was dark already by choice. Like I said, the music hadn't started, so we didn't experience anything like the lights suddenly go out or the electricity interrupting an electric rock band in any way. Instead, someone from the club got on stage and told us, "Folks, there's a blackout in the neighborhood. We don't know how widespread or how long it'll last, but we can't start the show."

Then he told us, "You can all stay and keep ordering drinks if you'd like while we try to wait this out, but our electric cash registers got stuck in the closed position," [laughs] "and we can't take credit cards," because that was all electric technology at the time, "so you'll have to pay cash and with something like exact change." That's what we heard from the CBGBs management.

We hung out for a while and then gave up. I was staying at my parents' house in Queens. I was actually between places of my own at that time and I was staying at my parents' house in Queens, but the subway was my ride home. Of course, it wasn't running, so the four of us walked from CBGBs up to my brother's apartment, which was on West 49th Street. With the air conditioning out, I basically slept on the floor in a steam bath.

Sam Pollard: Wow. That's a great story.

Brian Lehrer: One other thing though and I wonder if you want to reflect on this. It has to do with why you're doing this project. I have a memory of the walk on the way up. All the traffic lights were out, of course. I remember seeing people at various intersections spontaneously volunteering to direct traffic like role-playing traffic cop, which, of course, struck me as a very community-minded thing for people to do. It warmed my heart. The opposite of the fear and the looting that became part of the story in the press by the next day.

Sam Pollard: I remember that too, Brian. I do remember that people coming out in the street stopping traffic, going across town, and going uptown. I remember that also because I didn't see any looting, but I know there was some of it. The story you just told are the kind of stories we're looking for that we think will make this documentary very unique. This was a very interesting time in our city.

We had people like Bella Abzug, Abraham Beame, Mario Cuomo, Ed Koch. This was a really fascinating period in history. I was 27 years old. I thought this was the city that never sleeps and it was. That's what made New York, New York for me. We're hoping people will want to come forth with their stories and their footage and their videos if they have any or audios that can help us make this story even more special than I think it already is.

Brian Lehrer: 1977 was not an easy time in New York. It was the financial crisis. Things were going south. Services were being cut back. It was the Son of Sam summer with that killer on the loose. That was a tough year in general in New York, 1977, and the blackout happened. I was just talking about the traffic and you had that similar memory. I think Roger now in Tamworth, New Hampshire also has a traffic memory from the blackout of '77. Roger, you're on WNYC with director Sam Pollard. Hi.

Roger: Hi, guys. I had been kidnapped to New York by my friends who rescued me from my home in the suburbs and took me to an apartment on Second Avenue and 18th Street, where we were staying with my friend's brother, who was a science-fiction writer and still is, I believe. When the lights started to dim and it started to get dark, everybody whose windows were open on Second Avenue, once the lights actually went out, everybody started cheering up and down Second Avenue. Second Avenue is very long. That was the most amazing thing. Of course-

Brian Lehrer: Why?

Roger: -all of the traffic lights guys would see. I couldn't believe. Why were they cheering? [chuckles]

Brian Lehrer: Do you have a theory?

Roger: No, not at all. It was just such an unusual thing. I don't know. It was a kind of liberation in a sense.

Brian Lehrer: Roger, thank you very much. Just when things change, I guess, Sam, it's exciting.

Sam Pollard: Oh yes.

Brian Lehrer: If it's not too devastating, then even some kind of catastrophic change is exciting.

Sam Pollard: Well, I've heard stories of people in Brooklyn going up on their roofs, drinking, having a party. Some people really embraced the blackout. I was basically stunned. Sorry, go ahead.

Brian Lehrer: No, I'm just going to take the next call, so if I cut off a story there, you could finish it.

Sam Pollard: No, you go ahead.

Brian Lehrer: Victoria in Queens, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Victoria: Hi. Good afternoon. The crazy thing to this was that two weeks before the blackout, I escorted my mother to look at apartments in a new complex for retired theater people for seniors. Her apartment would have been the 17th floor. I looked at the woman and I said, "Do you have backup generators for your elevators?" She said to me, "What do you need that for?" [chuckles]

Two weeks later, I'm in the subway. Just brought my huge portfolio to FIT. It was the last exams. I got into whatever line it was at FIT and I had to get off at 34th Street. The train just managed to get one door onto the platform and everybody exited 34th Street that way. I had to walk up to 88th Street in Lexington to take care of my father, then back down Lexington to 81st Street to take care of my mother, who was dying of cancer.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, boy. Oh, my goodness.

Victoria: It was seven flights on one building and eight flights on the other. The eight flights was with water and food and whatever I thought she might need, so I got my exercise.

Sam Pollard: That's an extraordinary story, Victoria.

Brian Lehrer: That elder care. Oh, my goodness.

Sam Pollard: Wow.

Brian Lehrer: Dee in Yonkers, you're on WNYC. Hi, Dee.

Dee: Hi. How are you? I was a pre-teen, 12 years old, in the Bronx [unintelligible 00:11:12]. When it first happened, there was a deathly silence. Then what we realized was that nothing was working, no water, no elevators, no anything. The teenagers and the pre-teens in the building, what we all did was started walking up and down, getting buckets of water from the hydrants, taking it to our neighbors, helping the elderly people who were there by taking food from some of the other people who were in the building, helping some of the young ones when they needed formula. We ended up becoming the helps, but also the elevator, but it was so much fun. People started to really know each other after that. That was my experience that happened then. We still remember. We're still talking about it till today.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting.

Sam Pollard: Wow.

Brian Lehrer: A community-building experience in that respect.

Dee: Exactly, yes.

Sam Pollard: These are great stories, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want these folks to follow up with you in some way?

Sam Pollard: Yes, they can reach me at sampollard-- If I can give them my email address, is that all right?

Brian Lehrer: If you're not afraid of being trolled. [laughs]

Sam Pollard: No, I'm fine, sampollard@me.com. Just reach out to me. Those are great stories.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another one. Oliver in Brooklyn, like Dee, remembers the moment when it all went out. Oliver, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Oliver: Hi, Brian. First of all, I just wanted to say and many have said it before me, you and your show team are a national treasure. I've been listening since day one of On The Line.

Brian Lehrer: The old name of the show.

Oliver: It's been great. I just want to thank you for that.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. Very kind. Go ahead.

Oliver: Anyway, I was in the car heading west. The sun was going down. I think I saw a flash in the sky because I was going in the right direction. I think it happened in Yonkers substation, which is right next to the spring that I was about to get onto. I had the car radio on. It went dead, WCBS-AM. Then 15, 20 seconds later, they came back saying they were on emergency power. I drove down to see some friends in the Rochelle. It was just interesting to be listening on the radio while they were talking about it happening.

Brian Lehrer: Then boom. Thank you, Oliver. Actually, I should have looked it up, I guess, but I don't know the WNYC story and whether they went dead at that time. We did pull a couple of clips from our archives. Sam, if you don't know these, maybe you'll be interested in them. Because of the station's 100th anniversary this week, we've been really exploring the archives.

Sam Pollard: Oh, sure.

Brian Lehrer: We've got this of Mayor Abe Beame as the blackout had gone on for a number of hours recalling indirectly or referring here indirectly to the looting and other problems from a blackout in 1965, 12 years earlier. Abe Beame.

Mayor Abe Beame: I want to express first my total outrage that at this hour, the city of New York is still without power. The prospects for restoration of full electrical service remain vague as far as ConEd is concerned. Given what occurred 12 years ago, ConEd's performance is, at the very least, gross negligence and, at the worst, far more serious.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a little more Mayor Beame from the archives.

Mayor Abe Beame: We've seen our citizens subjected to violence, vandalism, theft, and discomfort. The blackout has threatened our safety and has seriously impacted our economy. We've been needlessly subjected to a night of terror in many communities that have been wantonly looted and burned. The cost, when finally tallied, will be enormous.

Brian Lehrer: One more from the archives. This one is New York City Police Commissioner Michael Codd, also making a comparison or, as he'll argue, making no comparison to the 1965 blackout. I don't know the full context. I'm curious with the research you're doing, how you hear the context of this clip, but here he is.

Michael Codd: There was less than 100 arrests in 1965. There were no significant injuries in 1965. The arrest figures for this period, you've heard, in excess of 3,500, or 3,300 rather, and the injuries, as I said, substantially above 100. We make no comparisons. We don't try to figure out what the different factors may be or the different causations.

Brian Lehrer: Are you familiar with any of those clips or have any reaction to them, Sam?

Sam Pollard: I don't remember any of those clips. I barely remember the '65 blackout. I was 15. I was living in East Harlem at the time. I think I remember being stuck on the elevator for a few hours with a bunch of other people. It was packed with us on the elevator and they had to figure out how to open the doors and to get us out. I don't remember the blackout like I remember the one in '77. When the police commissioner was mentioning the number of arrests that were less than '77, that makes sense to me. Abe Beame. All I remember is that those of us in the city thought Abe Beame should no longer be mayor back in '77.

Brian Lehrer: By the end of that year, he wasn't as Ed Koch-

Sam Pollard: He was gone.

Brian Lehrer: -was elected that same fall. Here's another Harlem memory and, in fact, police-oriented. Michelle in Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Michelle.

Michelle: Hey, Brian. You dissed me at the Museum Mile, but I still love you. We were living on 142nd--

Brian Lehrer: I don't know what that means.

Michelle: I bumped into you. I said, "Hey, Brian." It doesn't matter. I still love you. We were living on 142nd Street between Broadway and Riverside. I'm sleeping nine o'clock. My brother wakes me up. We're on a lower floor. He says, "There's something going on up the block." I crane my window. All of a sudden, I see looters going into stores up on Broadway. Then I hear cops shooting up into the air nonstop. It was like roaches. The looters, every time the cops were shooting up in the air, they disperse, but then they came back.

I watched this mayhem for maybe 15 minutes and I went right back to bed. Six o'clock in the morning, I wake up. I want to see what's going on. Go up to Broadway, which is right up the block, and I see total, total desolation. The stores, the glass was caved in. There were still people on the street going into the stores, but the cops were standing around just taking it all in. I walked up and down Broadway just surveying the results. I think I was a sophomore in college at the time.

The front page of The Times at that time was all about Beirut, Lebanon, and the pictures of this mass destruction. I'm like, "My God, this is happening right here." Anyway, that's my story of '77, but it was really something else. I also remember the '65 blackout. I'm going off now. I was a little kid. We were living with a Chinese family, who basically operated mahjong parlors in their home. The blackout occurred. They continued playing mahjong by candlelight. That's my story of 1965 blackout in New York City.

Brian Lehrer: Michelle, thank you very much.

Sam Pollard: Nice story.

Brian Lehrer: If you're willing, hang on and we'll take your phone number or contact information of any kind and give it to Sam because he may be interested in following up.

Sam Pollard: I would love to.

Brian Lehrer: One more text from a listener and then I'm going to ask you a closing question. This says, "I was 16 in 1977 and getting high on the roof of a public school in my Brooklyn neighborhood. I saw a flash in the sky at around dusk and then the lights all went out. All the kids from the neighborhood gathered on their corners and the boys walked all of us girls home to make sure they were okay. It was a fun night and hot too. The next day, all the hydrants were opened in the neighborhood."

Sam, are you looking for certain kinds of stories or pursuing certain kinds of themes or hypotheses? Because, obviously, you're best known for films associated with the Black experience in the United States in one way or another, all your work with Spike Lee and everything. Is that going to be central to this in any way?

Sam Pollard: No, I think in this particular case, just from the people who've come on the phone, those are the kinds of stories we're looking for that gives us a sense of the diversity of the city, the different approaches. The young lady who said she looked out her window down on 42nd Street in Broadway. Then the next day, she got up. The gentleman who told his other story, that's about being near the train. We're looking for just a level of diversity from all people, from all walks of life, from all races to tell this story. That's what I think it's going to make it a very powerful, powerful documentary.

Brian Lehrer: Just say one last time, how people can get in touch if they want to contribute.

Sam Pollard: Just reach out to me at sampollard@me.com. P-O-L-L-A-R-D, sampollard@me.com. I would love to hear from people and their stories that they have to tell. The stories I've heard today are just fantastic.

Brian Lehrer: Sam, always great to talk. Thank you so much. Good luck with the project.

Sam Pollard: Great talking to you, Brian. Be good. Have a good day.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.