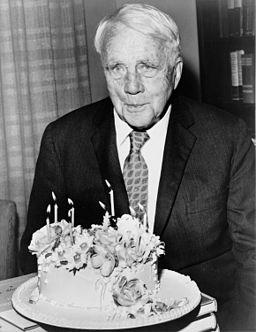

Robert Frost is honored at a 1958 Poetry Society Dinner

"Does wisdom matter?" Robert Frost asks. The answer is a resounding, No! America's most famous poet, being honored at this 1958 Poetry Society dinner, forcefully tries to disassociate himself from the public's image of him as a bardic sage. "I can't describe myself as I've heard myself described," he says, referring to the preceding testimonials (which are not included in this record of the event.) He then somewhat contradicts himself by addressing what he considers the essential problem of mankind: the anxiety we feel "lest the spirit should be lost in the material." We all experience this anxiety of being too material. Just look at the scales people now have in bathrooms! But we cannot shy from the material, either. "God, at the risk of spirit, descended into flesh."

Turning to poetry, he twits his colleague John Crowe Ransom who complained that Frost always "writes on subject." "Yes," Frost retorts, "and you write on bric-a-brac." He defends the use of rhyme and meter (Howl had just been published two years ago) and then reverts to his own fears that the material will "clog" his spirit. He speaks of the late psychiatrist and poet Merrill Moore who, when Frost would complain of this or any problem, would counsel, "You must do the best you can."

Frost looks back over his career, saying "I had so much luck," and then turns to what is clearly the main event of the evening, a reading of his poems. But he does not "read" or "recite." As always, with Frost, he makes a point of announcing that he will "say" a few poems, neatly emphasizing how much the quiet, spoken voice permeates his poetry. It is the music of a man "saying," not singing or declaiming. Working from memory, he stumbles a few times (Frost was eighty-four) but still leaves a valuable record of the way he intended his poems to sound. He makes some interesting asides, particularly about Mending Wall. When taxed by an English novelist about the line "Good fences make good neighbors," he defended himself by saying, "I was only quoting!" And when he gets to the lines:

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down. I could say "Elves" to him,

…he says, in an aside, "…as Yeats would."

There is then a break in the recording. Two poets are summoned up to the dais. It is not clear if their tributes took place before or after Frost's reading. John Ciardi reads "A Sonnet for Robert Frost" and Donald Hall reads his sonnet, "T. R." The recording then breaks off abruptly.

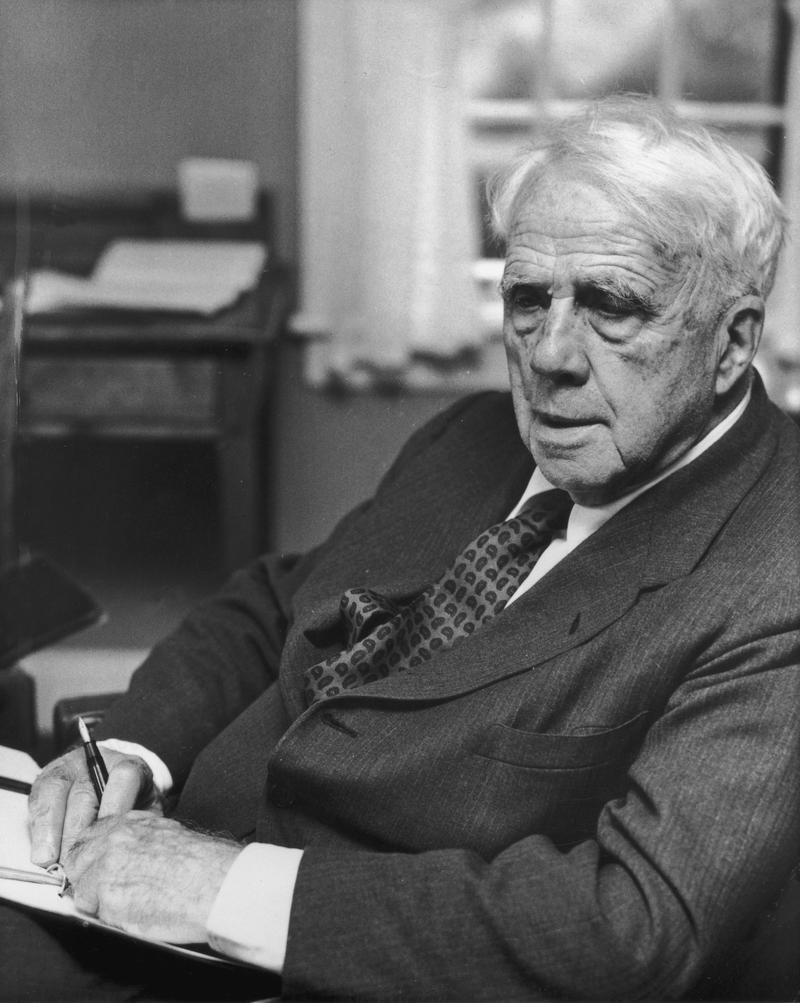

Robert Frost was born in 1874. His career was slow in taking off—he worked as both a school teacher and a farmer—but when it did, first in England, then in the United States, he quickly rose to become not only the nation's preeminent poet but its most popular as well. The reasons for this are easy to see. He achieved the almost impossible-sounding feat of fusing the simple, homespun voice of a skeptical, modern, unpretentious man with the commonly accepted devices traditional poetry. The website poets.org describes this seeming contradiction:

Though his work is principally associated with the life and landscape of New England—and though he was a poet of traditional verse forms and metrics who remained steadfastly aloof from the poetic movements and fashions of his time—Frost is anything but merely a regional poet. The author of searching and often dark meditations on universal themes, he is a quintessentially modern poet in his adherence to language as it is actually spoken, in the psychological complexity of his portraits, and in the degree to which his work is infused with layers of ambiguity and irony.

In his performance at this dinner, as he did in countless appearances throughout the country, Frost reinvents the notion of the public poet not by stressing a social or political agenda but by offering his poetry as a spoken remedy, as embodying possible clues to curing whatever ails the listening audience. The website of the Poetry Foundation lauds how:

He wanted to restore to literature the “sentence sounds that underlie the words,” the “vocal gesture” that enhances meaning. That is, he felt the poet’s ear must be sensitive to the voice in order to capture with the written word the significance of sound in the spoken word.

By the time of this dinner, Frost had attained an iconic status unheard of for 20th century poets. What differentiates him from subsequent "media creations" of our time is perhaps the degree to which his reputation was based solely on his books and readings. He did not endorse toothpaste, appear in films, or host a radio show. As The Paris Review noted a few years later, when choosing him as one of its first poets to interview:

The impression of massiveness, far exceeding his physical size, isn’t separable from the public image he creates and preserves. That this image is invariably associated with popular conceptions of New England is no simple matter of his own geographical preferences. … His special resemblance to New England is that he, like it, has managed to impose upon the world a wholly self-created image. It is not the critics who have defined him, it is Frost himself.

Robert Frost died in 1963.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 8733

Municipal archives id: LT7888