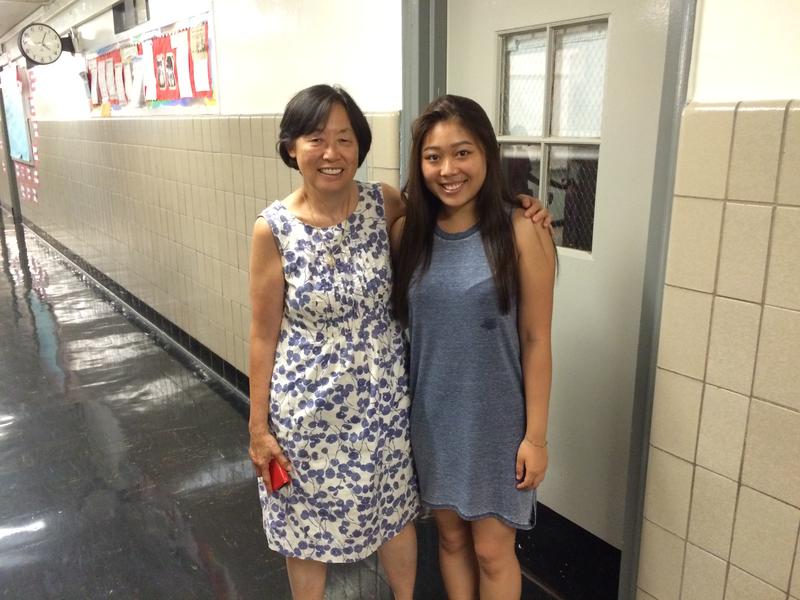

Seventeen-year-old Vicky Pan lived with her grandparents in the city of Fuzhou, China, from the time she was a baby until age four. The arrangement, common among many immigrant groups and struggling families, allowed her parents to gain an economic foothold in New York City where they worked in restaurants.

But separating from her grandparents, and reuniting with parents she didn't remember, was difficult. Thirteen years later, she teared up recalling her first night home in Queens because she missed her grandparents so much. "I didn’t want to cause any trouble," she explained. "I was, like, crying under my pillow."

Kids like Vicky are often referred to as "satellite babies," a term coined by researchers in Canada. While there are no long-term studies, researchers and educators have found satellite babies can suffer from attachment disorders and other mental-health and behavioral problems. As a result, there are efforts underway to encourage parents to keep their babies during the critical early years, or to at least bring them back sooner.

Locally, several Chinese community groups including Butterflies in Manhattan, the Chinese American Planning Council and Chinese American Sunshine House in Brooklyn provide workshops for parents.

Lois Lee, who runs the Queens office of the Chinese American Planning Council, said the recent expansion of free, full-day pre-kindergarten resulted in children returning earlier, at four instead of five. Lee said she'd like to see more free daycare options for younger children, too.

"That would really help to bring the children back earlier, so they can bond with their parents," she said.

For more on satellite babies phenomenon, listen to this NPR piece.

At P.S. 176 in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, there's a large community of recent Chinese immigrants. Principal Elizabeth Culkin said the children who were satellite babies often seem especially insecure.

"They’re always looking around to see who’s there with them," she explained. "And they always need that sense of knowing where they are and who’s there to protect them."

Kindergarten teacher Brenda Tang said the one satellite baby she knows about in her class this year, Vivien Huang, was adjusting well. Still, she planned to talk to her mother about the importance of family time to strengthen the parent-child bond.

At P.S. 105 in Sunset Park, Principal Johanna Castronovo said kids who were satellite babies sometimes pushed other children or acted out in other ways to get attention. "It hurts to see them suffering," she said.

The separation also is painful for the parents.

"They feel ache in the heart," said Rhoda Wong, an assistant professor of social work at CUNY's New York City College of Technology.

Wong wrote her doctoral dissertation on satellite babies. She interviewed 16 moms from the Fujian province of China who all sent their children to stay with relatives because they needed to save money or pay back debts. Wong said they felt guilty about it.

"All these mothers in the interview, they cried," she said.

Most mothers kept in touch with their children through video chats and telephone calls. Still, Wong said, she'd like to see more mental health providers who speak Chinese dialects, to treat mothers for depression and anxiety while the children are gone, and to help them with reunification.

She noted the city's own statistics: more than 8,000 babies are born each year to immigrant mothers from China. Although there's no way to know how many of them are sent abroad, Wong said there are surely a lot of parents and children in need of therapy and support.