The History of the 'Swans of Harlem' Told in New Book

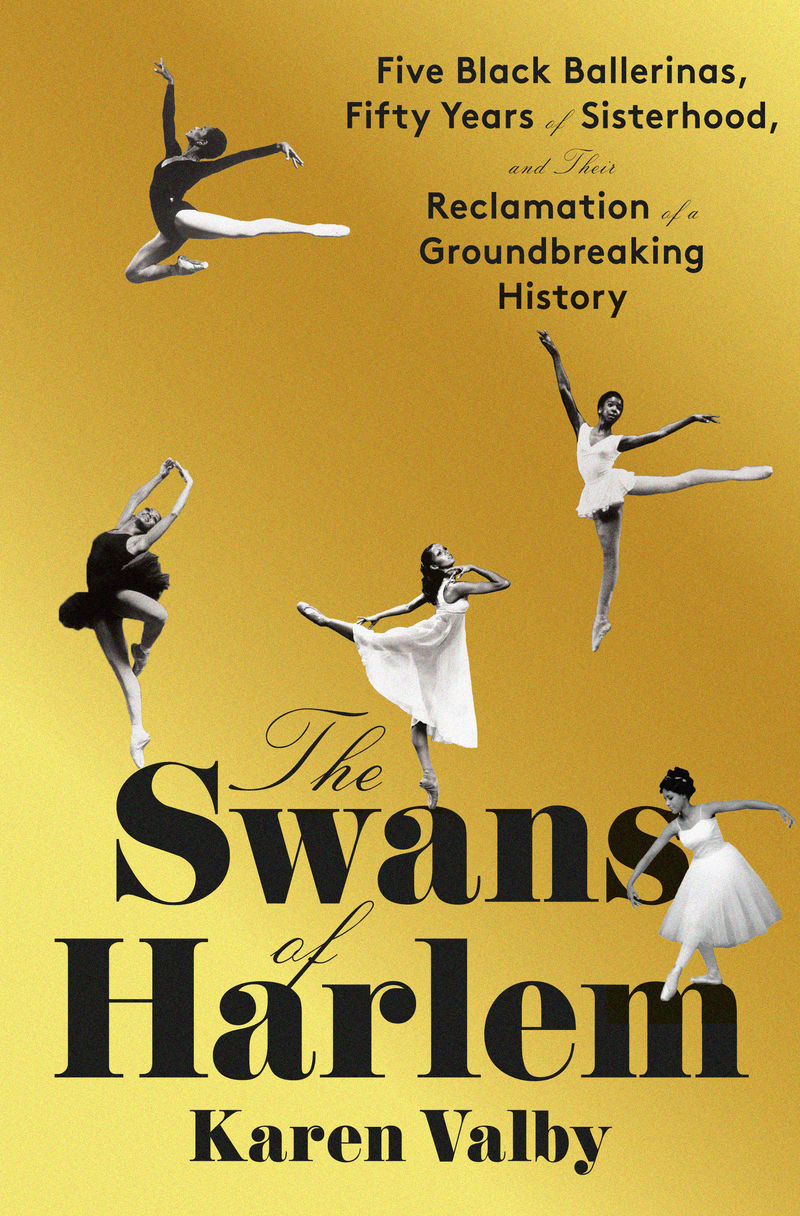

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

A new book tells the little-known story of the first principal ballerinas in the Dance Theatre of Harlem. It spotlights five dancers who broke barriers, performing internationally in a world where Black ballerinas were not expected or, in some cases, welcome. We speak to The Swans of Harlem author Karen Valby and one of the subjects, dancer Marcia Sells.

*This segment is guest-hosted by Tiffany Hanssen.

[music]

Tiffany Hansen: This is All Of It. I'm Tiffany Hansen in for Alison Stewart. Thanks so much for joining us today. On today's show, we'll talk with Denise Torres about how to become more financially literate, we'll learn about the spooky new film called I Saw the TV Glow, and one of the local finalists in the Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Competition and Festival will join us and perform live in studio. That's the plan, so let's get started with the Swans of Harlem.

[music]

Tiffany Hansen: In 2015, Misty Copeland became the first Black woman promoted to principal dancer in the American Ballet Theater's 75-year history. She was not, however, the first professional Black ballerina. Before Copeland and a small but influential group of other Black dancers, there were the Swans of Harlem. The Swans, as they're referred to in the new book by Karen Valby, are the Black ballerinas who paved the way for dancers like Misty Copeland. Until now, the stories of these dancers has largely been forgotten. Not by the dancers themselves, of course, or by their families, but by history. Karen Valby's book, The Swans of Harlem, trains the spotlight once again on these remarkable women centered on the lives and careers of five dancers, Lydia Abarca, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Sheila Rohan, Karlya S. Shelton, and Marcia Sells. The book details their struggles and successes at a time when it was unheard of for a production to include a Black dancer. Joining us to talk about the book is author Karen Valby. Karen, welcome.

Karen Valby: Thank you.

Tiffany Hansen: Also with us today is Marcia Sells, one of the dancers. Marcia, welcome.

Marcia Sells: Thank you very much.

Tiffany Hansen: Marcia, I want to start with you and just get a sense of how this book came about. I'm going to just generically refer to all of you as the Swans because it's such a lovely term. You connected with the Swans long before the pandemic, but as I understand it, it was a concerted effort during the pandemic to connect in a more meaningful way via Zoom. Is that how that went about?

Marcia Sells: Yes. I think what was happening probably across the globe is people were connecting and using means to stay connected to people and even thinking about people who you'd been connected to early on in your life. Many of us were-- and probably doing some reflecting on both where we are in that moment, as well as where we'd been and how we met each other. For all of us, we met, some earlier than even me because they're founding members of the company, but I met the members of Dance Theatre of Harlem, particularly Lydia. At the time, Lydia, Gayle, and Sheila, when I was in Cincinnati and very young, and they were coming to Cincinnati to form for their first tour. That's how far back, back in the '69, '70, that we met. We even as dancers stayed together, but even afterwards, and so COVID definitely made us think, how do we start talking about where we are? I will say, hearing for some of us that people were only thinking in terms of Misty Copeland as the first Black ballerina, knowing that we were ballerinas before Misty was even born, so it's like, why not start talking about it, and how would we do that? That was how we started getting back together.

Tiffany Hansen: It was both a bit of a connection during a really isolating time, and also, you kind of had the book in mind or just-- [crosstalk]

Marcia Sells: Oh, we had in mind telling a story. Did we have in mind this book? No. All of this is honestly magic and wonderful, as they say, cherry on top. It was, let's make sure that we're telling our story, realizing that there was a responsibility for us to do that and take that on.

Tiffany Hansen: When you were on Zoom together, was it mostly good memories or was it a mix? Was it a bittersweet reconnection?

Marcia Sells: Like all things in life.

Tiffany Hansen: Like all of life, right.

Marcia Sells: Also, realizing we've each reached a moment in our lives where we're in our-- well, for me, at the early days of reaching into my 60s, others moving into their 60s, Sheila moving into her 70s, 80s, you start reflecting on the things that have happened in your life and the way things came together. Also, when we got together, things that you remember on your own sometimes, but when you're in a group and you've been through the same situation, the kinds of things that come up, even some of the challenges and traumas of what it meant to be a ballet dancer, what it meant to be a Black ballet dancer, what it meant to be a Black ballet dancer dancing at Dance Theater of Harlem, and working with all of that, both the good, the bad, the wonderful things of being on tour, of being together, of being able to do our art form, as well as all the challenging things of why did Arthur Mitchell do this? Why did he make this choice? Sometimes, why did he push us so hard? Also, for us too, is why not also part of our story in the making of the company?

Because so much of it has always been focused on Arthur Mitchell and his audacious idea of creating this Black ballet company. As Karlya said the other day, when the curtain goes up, it's us. We were there.

Tiffany Hansen: Well, we're going to get to him in just a minute. Karen, I want to bring you in here and ask you, so did you sit in on some of those Zoom meetings? Were you thinking at that time, like, "I've got an idea, I've got a really great way to string all of these together?"

Karen Valby: Well, shortly after they formed the Legacy Council, Marcia lives on the same block as this magnificent literary agent Barbara Jones. She knows that I'm the mother of two Black girls who are dancers themselves. She knows what a Black dance studio in Austin, Texas has meant to the health of my family, so she just said, "Listen, why don't you take a meeting?" In that first meeting, I learned that Lydia Abarca, the first time she performed was to a nun's choreography to Waltz of the Flowers when she was in fourth grade. She got a scholarship to Juilliard, had that most high-end training for six years, and yet was never granted a chance to perform. Sheila Rohan, another Swan, was introduced to dance after she recovered from polio when she was seven and the doctor said dance is essential to your health. Gayle McKinney-Griffith, the first ballet mistress for Dance Theatre of Harlem, was training at Juilliard when the school told her, "You have no future in ballet, you need to switch to modern."

Karlya Shelton, the first Black American to represent America at the Prix de La Seine. Then, Marcia Sells, the baby who Arthur Mitchell taps at 10 years old and says, "You're one of us." This is in the first meeting all of this riches came out. There was a story to tell.

Tiffany Hansen: Well, I'm curious though as a writer, and I think you do this really well in the book, but these are five very distinct stories each with rich history, as you've just outlined. I can't imagine how difficult it was to try to weave that together. Just describe a little bit of your process in terms of trying to compile each of these stories and these histories, not only with personal histories, but the history of all of these other people that were involved. Process.

Karen Valby: Well, the through line is their sisterhood. These women who came together, who had each other's back at a time when the world said they didn't have a right to ballet, and so they've always seen each other so clearly. As long as I hung on to that idea that sisterhood is at the root of the book, I felt in good hands. The book does follow a three-act structure of the women's time in Dance Theatre of Harlem. Their second act is that disorienting time when you leave the stage. For many of them, the stage was taken from them. Then, the third act is them coming together to reclaim their stories and to enjoy this moment of being back in the spotlight. There's this line that repeats throughout the book that Sheila Rohan said was, "I was there. I was there." To have history tell the women that Misty Copeland is the first Black ballerina, she's magnificent and deserves all her flowers, but these women were there.

Tiffany Hansen: We've mentioned several times the Dance Theater of Harlem, right? Arthur Mitchell, very integral to this story. Let's start talking about that. First of all, Karen, tell us who Arthur Mitchell was. He was co-founder of the Dance Theater of Harlem, but who was he as a person? How did this dance theatre come about?

Karen Valby: He was a star. He was a genius. He was a visionary. He was the first Black principal dancer at Balanchine City Ballet.

Tiffany Hansen: Time frame for us, we're talking-- [crosstalk]

Karen Valby: This was in the '50s when Balanchine made him a star. After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, he realized art is activism and I'm going to go back to the neighborhood that I come from and I'm going to build a professional dance company and I'm going to show the world that the color of your skin does not determine your right to ballet.

Tiffany Hansen: He had a drive for making space for Black dancers. You have a quote in the book, "I'm going to found a company and it's going to be a great company." I love that confidence.

Karen Valby: Oh, Marcia.

Tiffany Hansen: Right. I was just going to say, Marcia, what is that-- [crosstalk]

Marcia Sells: The audaciousness. Also, you also think too, given his own life, where he comes from, his family finding dance through what was then performing arts school. Now we know it as LaGuardia. He realizes he has this talent, but I think probably once he's in City Ballet, as the only Black person in the ballet company at that time, figuring out how does he keep holding on to his value and his importance. As noted, it is the catalyst of the death of Martin Luther King that says, I can do this. I can bring Black people to this art form, also let the world know that we're capable. We're more than capable of doing it. That it isn't just him. You also have to think about it. Here he was the only one in New York City Ballet, but he wasn't thinking that he was the only one. He knew that there were probably others out there. I have to say there's times when I think of that scene in the film, Harriet, towards the very end about Harriet Tubman, when she whistles and makes a call, and you see in that scene all of this magnitude of Black people coming. That's what happens when Arthur Mitchell says, I'm starting a ballet company. This whole magnitude of Black people who realize, I don't have to be the only one.

If I'm like Karlya in Denver or me in Cincinnati, or somebody else who's-- Karen Brown down in Augusta, Georgia, you realize, "Oh my God, he's calling out," and I had this opportunity to do all the things that I wanted to do, to dance on point, to do ballets from the Balanchine ballets to then we do CREO, Gisele all. It's like, I can do this, and we did it, and people raved about it, and we had great reviews. That's a huge moment that he knew that it wasn't just him, that he could indeed find all these others and then train a whole new generation.

Tiffany Hansen: Karen, your description of him sounds imposing, larger than life, maybe really hard sometimes. Marcia, I'm wondering, when you first met him and when you were young, what did he seem like to you?

Marcia Sells: When I first met him, he seemed like a giant. He is taller, although he's not really taller than my father. My father was six foot four, but in that moment of meeting this man who has already danced on the dance stage, and also, I am a kid, I'm under 10 years old, and I've been living for all that time as the only one in my ballet studio, but to see him and to see his company, it's like the realness of what is possible hits me. I do think of him as like he's larger than life, and his word carried weight. When he says to me, "You--" although he doesn't say it to me, but he says it to my parents, she has talent, it's like, okay, I can just go on. Even when he taught class at the summer intensive, I will say, you're just-- There's no other way. Your body is at such a level of tension. Even now as I talk about it, I'll sit up straight. I think about trying to push and extend to the fullest. When he's saying and pushing it, those are the things that I still hear in my head, even when I think about the moments of how much it was a challenge, but to get that good, you have to be pushed.

There is a part of that that is the nature of ballet. I don't care who you are, but to get that good, to perfect a body that wasn't really meant to do turnout and be on point, you have to have a kind of commitment, and he really solidified like, this is what it's going to take to get to this level.

Tiffany Hansen: Do you view this book, this time as an opportunity to turn around and become a mentor the way he was a mentor and an encourager the way he did for you? I'm assuming, Karen, you can chime in with some other good stories from the other Swans who aren't here today, have similar recollections of him. Is it a moment where you're really thinking about that?

Marcia Sells: Oh, completely. Even when we started the conversations and even starting the Legacy Council, it was with the idea that when we tell our stories, if you are a young person now in the 21st century, young Black person in a ballet studio thinking, why aren't there more of me? We tell the story that there have been more before you and that there can be more, and that there's a whole group of people not only behind you, but that you could reach out to and talk to about what is it like.

One of the things that we realized too when we meet Karen and she's telling us a story about what she feels as a mom for her daughters, we realize we have that opportunity to really provide, here's a whole history. You have a history behind you. You don't have to think of yourself that there was this one. No, there have been many, many. We're here to provide you insight, to share ideas, to help you understand because we've been there. That I think more than anything, and not only telling our stories in the context of the book and the Swans, but also to tell the stories of the other Black dancers who were all there with us and that were part of us, and some who are not here with us anymore, but to make sure that they also live too.

As you said, mentor, yes. If our story can do that for young Black dancers coming up, and even encourage a whole new group because I still think that there's some people who think sadly, even in this day, that ballet is white. Even though Alonzo King has a ballet company and then there's Complexions and there's the Black Ballet and there's also Ballet Ethnic founded by two former members of DTH, but still in terms of really flooding it that this is an opportunity that you can express yourself through this art form, and it still can be authentic and still be you, if we can make sure that that happens more, that'll be great.

Karen Valby: I just want to say quickly, there's a moment in the book where the Swans meet Misty Copeland, and it's this beautiful completion of the circle, but she said with such frustration in her voice that she hadn't even heard the name of Lydia Abarca, the first Black prima ballerina until she read the New York Times article we published in 2021. There was such sadness to hear her say, I didn't know these women's names. She was robbed of the example of community. That vacuum leaves her more isolated in her sense of what it is to be a Black ballerina during her time at ABT. It felt like a tragedy that she too hadn't heard of the Swans. They're part of her legacy.

Tiffany Hansen: Right. Marcia, speaking of Misty Copeland, I can imagine if I were in your shoes, and there was a lot of press around this, as Karen said, very deserving young woman, she deserves all her flowers, but I can imagine feeling like, Hey, wait a minute. How was meeting her? How is it when someone talks about her? Do you still have a little pang of that-- [crosstalk]

Marcia Sells: I've met her a few times. I happened to be working and missed that moment of meeting her in Boston, but she and I actually met because I work at the Metropolitan Opera and American Ballet Theater performs there. Just after her son was born, she was in the house at the Met, and we have chatted and knew about the meeting. For me, to Karen's point, it's not so much about her getting flowers. It's that either media or even, I will say, the American Ballet Theater, did not think about the idea that there were people before, because they know. Ronald Perry actually was a soloist with the American Ballet Theater during the time when Baryshnikov was the artistic director. It's not a, they don't know. Keith Lee, also a Black dancer who was in ABT. They know that there's a history, but not letting Misty or even their own public know that this is part of a whole tradition, this is an extension, I will say, I always thought that that was, as Karen said, the robbing Misty of the opportunity to be part of a collective and not to be seen as somebody who's so unusual and truly so deserving to have that moment to be a principal in that company. Not only it was time.

Debbie Austin is a early Black woman who is in New York City Ballet, one of the first Black female dancers in City Ballet after Arthur Mitchell in the '70s. Even continuing all of that history and not talking about it I think created a sense of-- I used the word unicorn. This notion that it's so unusual. We need to say to people, that's not unusual. That's not. This is the history. The same thing. Jackie Robinson becomes the first Black player and changes the whole face of sports as well as American history. We need that same moment in ballet. We need people to see it as this is not the end or that it was only this one, but that here's the many.

Tiffany Hansen: Karen, one of the great things about the book is the way you really transport us to this very specific, at least in the early chapters, into this very specific period in time during and around the civil rights movement. You mentioned the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. How is it to write for that moment in a way and really make it feel present so that these women's stories can rightly also feel present?

Karen Valby: Well, I think my job was made so much easier by having these five divine primary sources. Yes, I'm the author, but in the truest sense of the word, we were collaborators. We were in company on this, and these women aren't just magnificent performers. They're phenomenal storytellers, and they've had years, years waiting for somebody to be interested. It's funny, each of these women had such a personal journey in the company, but like Marcia says, they were a collective. What was so fun in interviews was you realize-- It was fun to see the women hearing stories for the first time. I felt like you all learned about each other in the course of reporting because just keeping your head up in a professional ballet company is crazy hard work. The memories just build on top of each other. Every conversation was so beautiful and so rich.

Tiffany Hansen: Crazy hard work. Crazy. Marcia, you lost toenails. Let's be real.

Marcia Sells: I wasn't the only one losing toenails. That is the nature of-- I'm sure there are ballerinas even now losing toenails, but it is the nature of the art form. You do have to love it because it is a commitment. Once you get past the age of eight and you start taking class four to five days a week, then it goes up to five, six days a week, and then you become an apprentice in the company and you're taking company class and rehearsals and everything else. Then, to get in a dance theater, and we all says this, Mr. Mitchell would always say, "This is something larger than yourself," to know that every time you step on a stage, you're trying to be the absolute perfection, because I think that's also the history of a lot of Black people. The notion of you have to be 10% better because people are going to think, oh, you just really can't do this. I'm like, listen, "I went to law school at a time when there weren't many Black lawyers and there still aren't many." It is knowing that that's possible and I can do that. I know ballet gave me that strength and foundation, but it is hard. It is hard. Most people don't walk around and point shoes and try to do turnout.

You're doing something that they say wasn't necessarily meant to be. How do you do that so it makes it look light and easy? You have to put in all that work and hours.

Tiffany Hansen: Right. Before we wrap up, I want to ask you. Arthur Mitchell is no longer with us. How did his death hit you?

Marcia Sells: Oh, wow. That's a biggie because I know exactly where I was. I was then working at Harvard Law School and a friend called me on the phone and said, "I don't want you to read this, you're going to know he just died." Probably because during those last few years, he and I had gotten very close. I had worked on getting his archive to Columbia University and getting his flowers before he passed away. There were wonderful articles both about the-- so I'd had that moment, I think, of reconciliation in a way that was very deep and profound, and feeling that I not only contributed both to his life, but also the history as we're talking to about Blacks in ballet, to have it in a place [unintelligible 00:26:08] people could do that. When I heard about his death, I had to go home. I needed care. My job was to take care of all these students. It was like, no, I got to go home. It was like also experiencing my own parents' death all over again because he was indeed a father figure.

Tiffany Hansen: So, so influential.

Marcia Sells: It was-- Yes. All of the emotions that one feels when you have been in close contact and in a life and that someone has been in a life and seen your life.

Tiffany Hansen: That's right. Karen, before we go, you mentioned this early on in the conversation, but one of the refrains in the book, we were there. That's really what this book is saying in essence.

Karen Valby: Yes. These women's lives mattered. Their art made a difference. Beauty has value, and one of the Swans, Gayle McKinney-Griffith passed last year, and the fact that she set her story down on record, the fact that her grandson gets to know her in completion as he grows up, and that the world gets to know about the beauty she made and the friends that held her up along the way. She was there, and it's very meaningful. It's very meaningful to celebrate her now and to still feel her with us. This is painful. This is a book about five Black ballerinas, and we're missing one. Thank God she told her story.

Tiffany Hansen: Marcia, thank you for sharing your story with us.

Marcia Sells: Thank you very much for having us. We're grateful that we found Karen, that, in some ways, when we think about a bunch of things, it was definitely meant to be. This-

Tiffany Hansen: The world-

Marcia Sells: - was meant to be.

Tiffany Hansen: -works in mysterious ways.

Marcia Sells: Absolutely.

Tiffany Hansen: Mysterious ways. Marcia Sells is one of the Swans in the new book, The Swans of Harlem. The author of that book is Karen Valby. Karen, Marcia, thank you again.

Karen Valby: Thank you.

Marcia Sells: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.