NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Tinseltown, Talkies, and the Celluloid Frontier

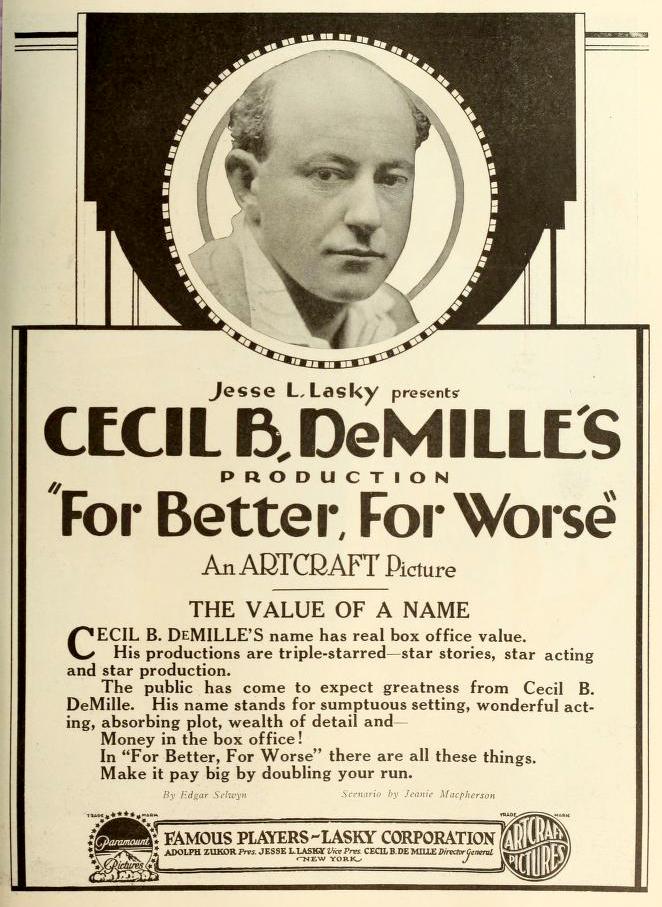

In 1915 Francis X. Bushman made the great migration to Hollywood to do what many established theater actors did at that time: slum it in that little backwater of a West Coast town (part of Los Angeles since 1910) to make some serious cash. Upon his arrival, Bushman —who would go on to become one of the first bona fide movie stars and an accomplished film director in his own right— was introduced around one of the studios to get a feel for the process. One of the first stops on this introductory tour was the set of none other than the great Cecil B. DeMille, where Bushman arrived to see a giant swimming pool filled with crystal clear water and a gaggle of nude actresses frolicking within. Above the pool an array of lights and a motion picture camera had been rigged to catch the action, and DeMille enthusiastically informed Bushman that the goal was to film the actresses in a way that only their backs could be seen as they swam, creating a tasteful yet tantalizing spectacle of grace and beauty.

Now, from a modern perspective, there are a number of reasons why this is a bad idea, not least of which is the potentially tragic and gruesome demise that might befall those poor women should one of those high-voltage lights come loose from its moorings. However, as Bushman was later informed by a crestfallen DeMille, the lesson learned that day was the folly in trying to film a reflective surface. (Think of what happens when you take a picture of a mirror). Instead of capturing in celluloid an image of ethereal beauty as tastefully nude nymphs frolicked in the clear water, all he recorded was a few hours of his own camera and lights looking back at him. It seems insane to think that a professional Hollywood director wouldn’t understand that you can’t point a camera directly at a mirror-like surface, but it makes sense when you think about the moment in context: it was 1915 and no one had ever tried that before. We can imagine DeMille smacking himself in the forehead as soon as he saw the developed footage and thinking, “You idiot, of course!” (Click on the audio player above for a snippet of this delightful anecdote.)

This is just one of the many colorful and informative tales recounted in Memoirs of the Movies, a radio program from the early sixties that featured prerecorded interviews with Hollywood greats, from the silent era all the way through the golden age of Hollywood and beyond. The list of legends who lend their considerable experience and flair to this program is awe-inspiring. It includes Buster Keaton, Dorothy Lamour, Gene Kelly, Arthur Freed, Paul Newman, Ben Hecht, Adolph Zukor, King Vidor, David O’Selznick, Basil Rathbone, Myrna Loy, Harold Lloyd, Cecil B. DeMille, Otto Preminger, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and many, many others. This collection of shows is a veritable treasure trove of film history, and some of the stories related here appear to exist nowhere else. What’s more, those involved in the program are actors and film directors, old-school producers, writers and musicians —in other words, professional storytellers with huge personalities and an immense talent for spinning a good yarn. And, boy, do they bring it! Jack Lemmon recounts his first meeting with Harry Cohn. Ben Hecht recalls the undeserved credit he received for the innovative camera movements of Lee Garmes in Angels Over Broadway (1940). Cecil B. DeMille recounts going to California to shoot 1914's The Squaw Man and —because he needed a locale with desert and prairie— renting an old barn on Vine Street that would later become the first Hollywood studio. Reginald Denham tells a hilarious story about legendary film producer Sir Alexander Korda and the insanely convoluted process of writing a script and getting it into production.

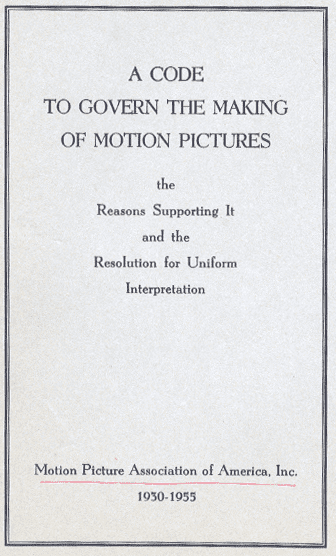

Throughout it all there’s a certain polite reserve to the series indicative of the era in which it aired and frequently absent from contemporary media. The ability to tell a good story, juicy bits and all, while being mindful of the censors and the public tastes was a skill developed early by the Hollywood set due to the rigors imposed by the Hayes Code and, later, the MPAA. It lends the proceedings a measure of class and old-school cool both charming and sophisticated, and makes the whole collection feel warm and inviting. These assets are true treasures and we at the WNYC Archives hope you enjoy them as much as we’ve enjoyed bringing them to you.

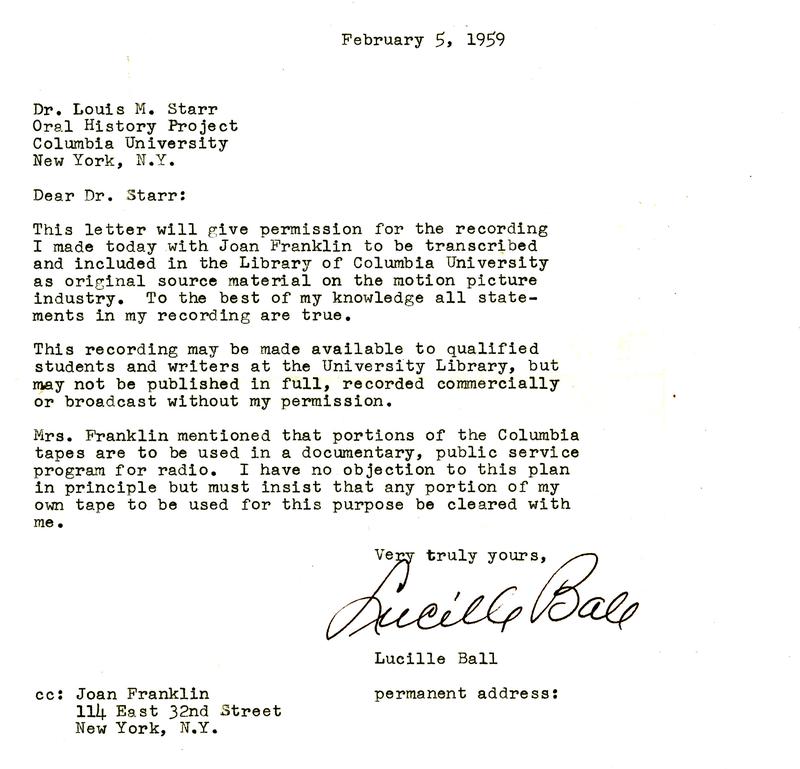

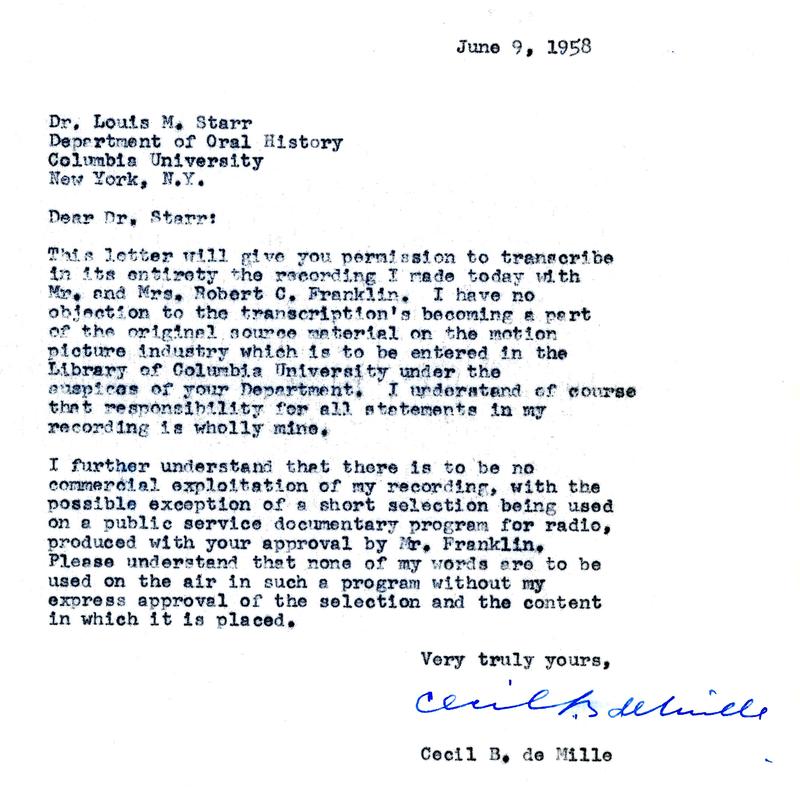

The Cinema Sound collection in the New York Public Radio Archives has several documents and letters related to Memoirs of the Movies that constitute a small treasure in and of themselves. Some of the letters and signatures on these documents are a film buff’s dream find; we’ve included two below. Also, there are a few episodes we’re missing: episode #17 The New Hollywood and episode #18 The Rusk to Reality. If anyone has heard them or has copies, please let us know here at the WNYC Archives —we’d love to hear them.