Fabiola went before an immigration judge in black, glittery shoes and a purple sweater with a pink peace sign on it. She’s five years old.

She had a federal prosecutor and an interpreter but no lawyer. She was at the court for hours, and every so often Fabiola would look up at the adults the room, raise her finger and warn them: “I don’t want anyone in here to give me a shot,” she would say in Spanish.

Fabiola thought she was at the doctor's office. Adults at the court assured her that they don’t give shots there, but Fabiola was skeptical.

Fabiola fled Guatemala without a parent or legal guardian. She walked for months with a friend of her grandmother's. Under rules set by former President Barack Obama, Fabiola is considered an “unaccompanied minor" because she made the journey without a parent or legal guardian. With that classification comes special protections mandated by Congress.

According to proposals from President Donald Trump, Fabiola wouldn't be considered unaccompanied because she was reunited with her mother who lives in New York.

Fabiola’s Journey

Fabiola was apprehended at the border about two months ago. She was separated from her grandmother's friend, held in Customs and Border Protection detention for three days, then sent to a shelter in Chicago. Twenty days later, she was released to her mother.

This is the standard process for unaccompanied children. If their parents are living in the U.S., they can step forward and claim their kids. The process can take months.

“It’s the most horrible experience there is,” Fabiola’s mother said. “Besides the anguish of her journey here ... I didn’t know where she was, if she was okay, if they were treated her well.”

According to a February 17, 2017 memo from Department of Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly, “approximately 60 percent of minors initially determined to be ‘unaccompanied alien children’ are placed in the care of one or more parents illegally residing in the United States."

Kelly called it an abuse, and has asked agencies to develop a system to reclassify those children.

The Protections for Unaccompanied Children

Unaccompanied children currently can apply for asylum and for a Special Immigrant Juvenile status. They can ask for time to find a lawyer, appeal decisions, and start the process over.

In the past 12 months, almost 12,000 children considered unaccompanied had a court hearing at the New York Immigration court, according to court data monitored by The Safe Passage Project. They represent unaccompanied children in their immigration hearings.

The Trump administration says there’s a backlog of cases for unaccompanied minors. If kids who are reunited with a parent are re-classified, the backlog could drop. But the protections would also disappear.

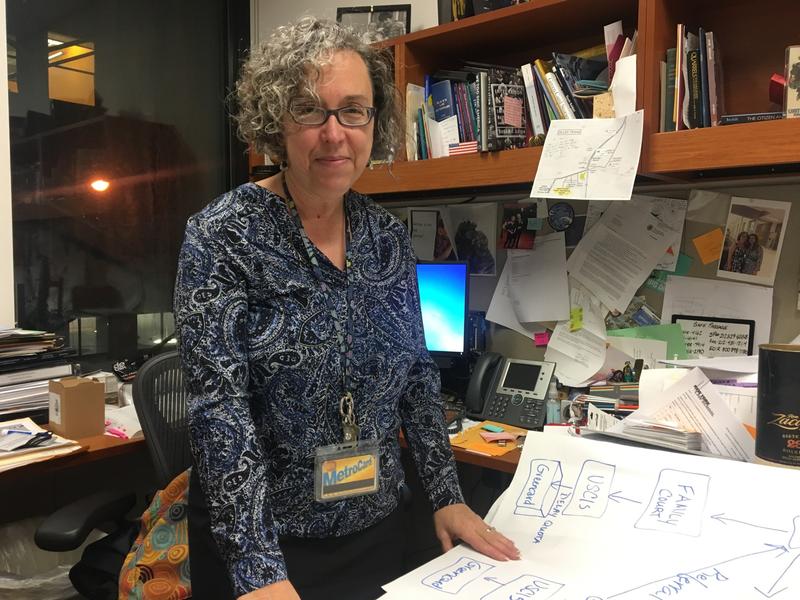

“If a child does have a parent somewhere in the U.S. Secretary Kelly’s memo seems to imply the child should be treated same as an adult,” said Lenni Benson who runs The Safe Passage Project.

Benson says that means kids can be deported the day they arrive at the border, and without any hearing.

Prosecuting the Parents

And there’s another big change outlined in Trump's plans: if a parent living in the U.S. illegally comes forward to claim their children, like Fabiola’s mom, the memo says federal agents may place the parents into removal proceedings or refer them for criminal prosecution because they would be seen as facilitating "the smuggling or trafficking of alien children into the United States."

Benson said parents will still come forward to claim their kids — they’ll just work through middlemen which has its own risks.

More than 200,000 unaccompanied children have been apprehended in the past four years, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Benson says masses of them have not tried to evade detection; they're surrendering themselves.

Benson said the new policies won't stop kids from fleeing dangerous situations back home: “They’ll just try to avoid detection more."