From the August 1940 WQXR Program Guide:

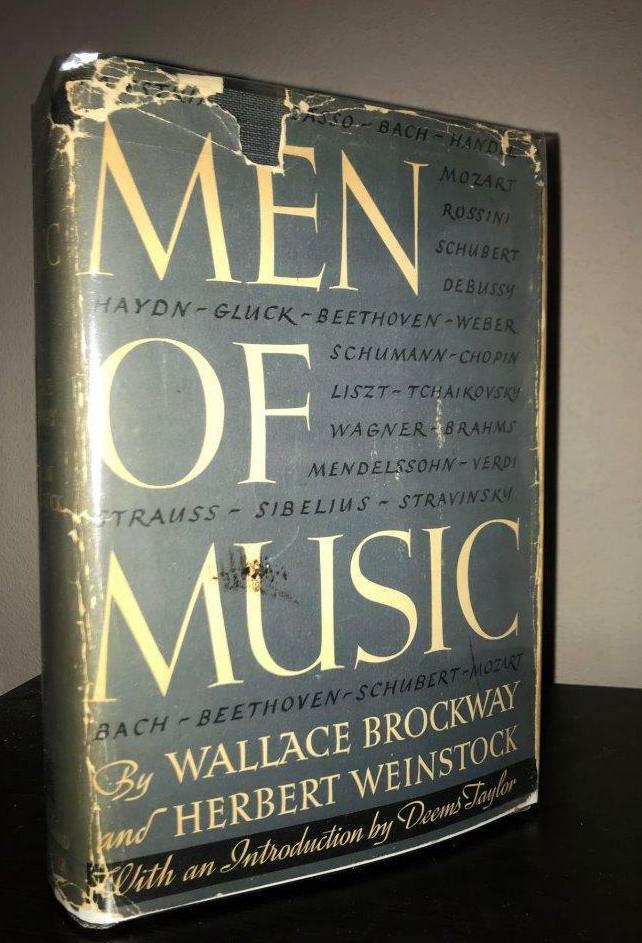

Wallace Brockway and Herbert Weinstock are the authors of the best-selling book of critical biographies, "Men of Music". They are at work on a history of the opera, to be published in 1941.

The music of lesser composers is starred with happy inspirations. Grieg and MacDowell, for instance, are sometimes so fertile in those points of departure which seem made to order for starting a masterpiece on its way, getting it over a difficult moment, or bringing it happily home, that we are momentarily seduced into believing that what we are hearing is a masterpiece. Young listeners of whatever age hear only these strokes of genius, and forget, or are deaf to, the acres of marking time between. An astute music merchant like Saint-Saens bunches his effects because he has to, and because he knows his own poverty. They are very impressive effects — while they last. Paging through the yellowing scores of George Philipp Telemann, Weber, Meyerbeer, and H. T. Parker — a hundred other names would serve as well — we come across a lush melody, a haunting harmonic progression, a canny rhythmic effect. Our first impulse is to disinter these giants and animate their lifeless limbs — an expensive job, whether at the Philharmonic or the Met. And we have our little triumphs: there are our effects, sure enough, but buried, sometimes lost, in a skeleton that will not take on flesh. Or, if it does for a time seem to live, it is only to collapse, fearfully and without warning, like Poe's M. Vladimir. Not even the interpretive skill of a Toscanini or a Gieseking can avert this nauseous catastrophe and give to the disinterred second-rate the vitality of great music. Romantics would have us believe that this vitality is merely the translation into musical sounds of noble thoughts and powerful emotions.

This would be an eloquent argument if it could be shown that the great masters had a corner on the noble thoughts and powerful emotions of their times. Actually, some extraordinarily feeble talents wallowed in the most virtuous thinking and indulged emotions that bordered on hysteria. Contrarily, a veritable first-rank genius like Handel seems to have had no personal emotion other than generous anger, while Chopin suffered from a positive dearth of noble thoughts. There really is not, and never was, a rule about such matters as these. And, indeed, if music were a faithful translation of a composer's personality, emotionally and mentally, listening to Haydn would be very dull and listening to Wagner an unendurable torture. Fortunately, the small portion of the personality that manages to pass through the filter of the creative imagination acts as nothing more than a coloring matter on the final product.

No. It is no less true of music than of any other art that what gives vitality is the artist's ability to think in terms of his art and his compulsion to work unceasingly, earnestly, with the tools of his craft. He must understand the larger architecture of his forms (whether as restricted as a Schubert song or as expanded as a Beethoven symphony), and he must understand not only the multifarious grammar of detail, but also the function of detail in creating pattern. That certain spiritual qualities Eire called into service by these processes, it would be idle to deny. But let us not try to make rules about them any more than about the ratio of noble thoughts and powerful emotions to musical vitality: they vary from composer to composer. Granted the original "inspiration" (which a Grieg or a Massenet, or a Moszkowski is as likely to get as a Beethoven), vitality then depends on what is done with it. Its exact character and potentialities must be understood above all, at this point, its innate vitality must not be overestimated.

It must be used in the right milieu, given to the right instruments, placed in the right keys, varied or mated with its legitimate complements. In his judicious handling of these various elements of musical creation, Beethoven is the mighty exemplar that leaps at once to mind. To follow one of those frequently rather commonplace germs of musical thought from its birthplace in his notebooks to its final series of grand progressions in a symphony, concerto, quartet, or sonata, is to spy upon the central secret of artistic creation itself, and to understand, in a measure, why some music is vital and other music is not.