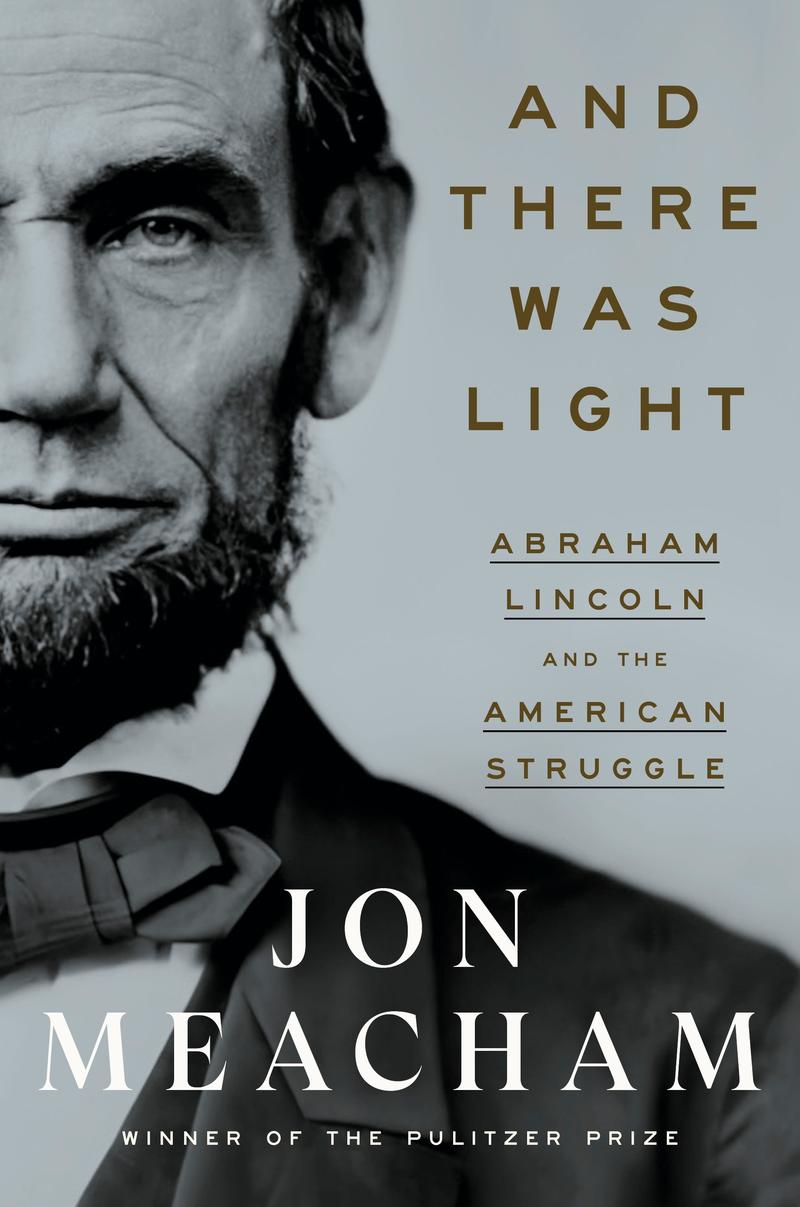

Jon Meacham, Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historian and the author of And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle (Random House, 2022), talks about his new book.

EVENT: Jon Meacham will be in conversation with Eddie Glaude at Barnes & Noble—Union Square on Tuesday, October 25, at 7pm. Registration here. He'll also be at Temple Emanu-el with Willie Geist on Wednesday, October 26th, at 6:30pm. Registration here.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. With us now is Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historian Jon Meacham. He has a new biography of a president who governed a deeply divided country, not Donald Trump or Joe Biden, President Abraham Lincoln. Confronted with the tragedy of slavery and the reality of secession, Lincoln has much to teach us about bravery and democracy a century and a half after his assassination, but Lincoln was also a morally imperfect figure.

He was, in the words of the great sociologist WEB Du Bois, according to the book, a big inconsistent, brave man. Let's see why Jon Meacham has returned to studying Lincoln in the context of helping us through today. Jon Meacham, again, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historian, and he is the author now of And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle. Jon, so glad you could join us for this. Congratulations on the book and welcome back to WNYC.

Jon Meacham: Thanks for having me. Appreciate it.

Brian Lehrer: I heard a stat that 15,000 biographies of Lincoln have been written second only to Jesus. To start out, how do you hope to add to our understanding of one of the most biographed, if that's the right word, people of all time?

Jon Meacham: You know, I've written about Jesus too, so I need to figure out some new to-- Maybe I need some new topics. Look, I think that for a biographer, I think Lincoln is a little like Mount Everest. You need to try to climb him. My sense is that I wanted to answer the question not only how did he do what he did, but why. Why was it that this anti-slavery, not abolitionist but anti-slavery politician stood by that through the 1850s when he lost two Senate races? He barely wins the presidency, 39% of the vote, in 1860. He stood by the cause of Union, which became the cause of abolition at moments when the politics of the moment and a lot of voices in his ear they'd argue for the opposite.

What was it, what was the voice in his head? What was the picture in his mind to which he was tending? The answer, I believe, is that he genuinely believed in the words of Theodore Parker that Dr. King used and President Obama had put in the carpet in the Oval Office, that the arc of a moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. Lincoln understood that that arc doesn't bend by itself. That it requires people of goodwill who understand that democracy is not just about taking, but it's also about giving.

Brian Lehrer: The prologue of your book begins on the day of Lincoln's second inauguration in early March of 1865 when Union forces were on the verge of victory in the Civil War. What did Lincoln say in that second inaugural address? Maybe not his most famous speech. Obviously, the Gettysburg Address is his most famous speech. What did he say in that second inaugural address that made you start there?

Jon Meacham: An American president stood on the east front of the Capitol. Remember, they didn't move the inaugural around to the west front until 1981. He stood there in front of a little white table, adjusted his eyeglasses, and actually said that it may very well be that the only way to atone for every bit of blood drawn by the lash of human enslavement, that the only way we can get through that is perhaps it has to be answered by an equal amount of blood drawn by the sword of war. It's breathtaking. Just sit with that for one second.

That's an American president saying that there's a divine force that is particularly interested in our national story and our moral conduct toward one another and that there is an eternal standard of justice to which we must tend. Be great if we could get there, but tending is about all we can do. That's the nature of a fallen world. When I went over that, I realized that's a profoundly theological vision of the world coming from a guy, let's be clear, who was in no way a conventional Christian.

I'm not rebaptizing Abraham Lincoln retrospectively. He was basically a New England transcendentalist universalist who loved the King James Bible. We've done worse [laughs] than having that. I think that my ultimate point here, and we've seen the wages of this tragically in our own time, is if you send someone to power who does not have a moral sensibility, then that is in fact fatal to the American experiment in liberty under law.

Brian Lehrer: We won't name names, but to stay on the theological idea, is that why you titled the biography And Then There Was Light?

Jon Meacham: I owe this as we all owe so much to Frederick Douglass who said in that great 4th of July oration, actually delivered on the 5th of July in Rochester, New York. Douglas said, "I do not despair of this country. The fiat of the Almighty, let there be light, has not yet spent its force." It fell to Lincoln in many ways to be the instrument by which that light was shed. It wasn't enough. It still isn't.

One wishes to stay within the metaphor that it was a brighter, warmer, more just light, but think of the darkness that was descending and had descended over the United States of America in the late 1850s. A huge number of people from my native region of the South decided to put their own racial and economic power over the central claims of the Declaration of Independence and the importunings of conscience. As Lincoln said, "As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master," that expresses my idea of democracy.

Brian Lehrer: If you're just joining us, my guest is the presidential historian Jon Meacham, who has a new book called And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle. We'll get to the relevance for today a little more directly in a minute, but I saw you talk on TV on MSNBC about Lincoln grounding the Gettysburg Address in the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution. That's an important distinction. Would you talk about that here?

Jon Meacham: Lincoln actually said using an image from Proverbs that there was an apple of gold and a frame of silver, and the apple of gold was the Declaration of Independence. That that's the nation's mission statement. The Constitution is a user's guide. That's me, not Lincoln, obviously. The Constitution was an attempt to create a context in which the declaration could be realized as imperfect as that instrument obviously is. He believed that the American story in many ways begins with that declaration, and with the assertion, as he put it, "My ancient faith--" He used the words, "My ancient faith teaches me that all men are created equal." If that is your lodestar, if that is the goal, then you are embarked on--

Brian Lehrer: Oh, I think we've lost Jon Meacham there for a second. We'll get his line back. I'll tell you what I'm going to ask him next based on the answer that he was just giving and what I know is in the book. Lincoln did not actually believe that all men were created equal. We'll get to that follow-up question in a second. Jon, we have you back. Did you want to finish the thought you were in the middle of?

Jon Meacham: Yes, I do. If you don't have the principles of the declaration at the center of the project and the project is once human and humane. It's human in the sense that it's incomplete, right? We don't do everything we're supposed to do. It's humane because it's what we are called to do.

Brian Lehrer: He did not actually believe that, to cite the declaration, all men, all people were created equal. As I understand you, he believed white people were created superior to other races, and yet he was committed to the abolition of slavery in all the ways that we know he put himself on the line. Given the first belief, how did he get to the second?

Jon Meacham: It's the great tragedy of Lincoln and of America. There's no sugarcoating it, there's no to-be-sure-ing it, this is not a casual caveat what I'm about to say. Lincoln articulated this vision. Nobody ever articulated it better, and yet he chose, and I use that word advisedly, he chose not to follow the logic of his own argument to the point where Black Americans could be equal citizens to where we could build what John Lewis and others would think of as the beloved community. Lincoln was not a racial egalitarian. He was not Martin Luther King in a stovepipe hat.

We do ourselves no favors if we either skate over that or if we try to condemn him reflexively. I'm a firm believer that the moral utility of history is to see that if even good and great people of past eras could get such fundamental things wrong, then we need to be aware of what we are getting wrong in our own time because somebody's going to be looking back and holding us to account. I don't believe we should look up at Lincoln adoringly, but I also don't think we should look down on him condescendingly. Look him in the eye so that when we look in the mirror, we'll see more clearly.

Brian Lehrer: To what degree did you write this book to help us look in the mirror today?

Jon Meacham: It's a huge motivation. It's biography, it's an exploration of his philosophical themes, but it would be foolhardy not to be totally straightforward that it's informed by the crisis we face, an unfolding crisis of democratic values, lowercase D, and deepening division. Without understanding, it seems to me, why the country is worth defending, then its defense will be insufficient.

I believe that as imperfect as we are, there is at this point not a plausible alternative that has presented itself. The alternatives that have presented themselves are autocratic, borderline, they're dictatorial, they're illiberal. They deny elections and realities and the reality of that Declaration of Independence. I believe that being in conversation with Lincoln, being in conversation with that era can help arm us for this struggle.

Brian Lehrer: Presidential historian Jon Meacham's new book is called And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle. Thank you as always Jon for sharing your thinking with us. We always learn when we hear from you.

Jon Meacham: Very grateful to you. Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.