The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

When a Mental Health Crisis Prompts a 911 Call

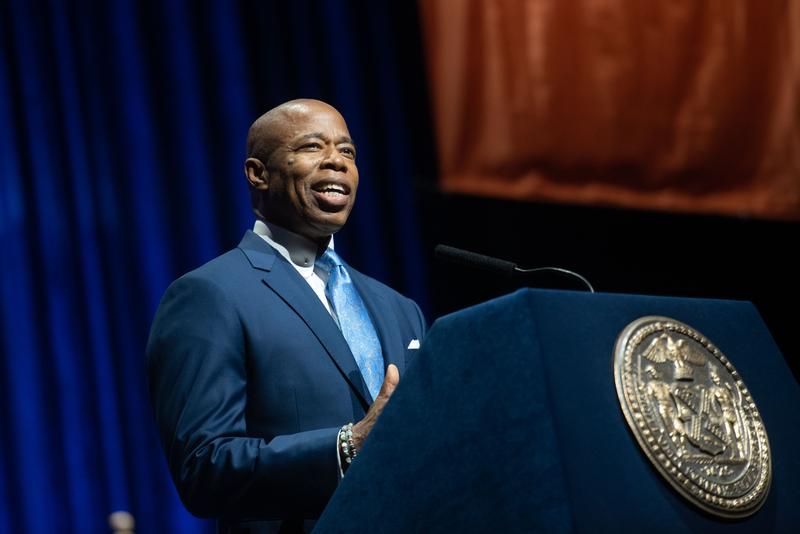

( Michael Appleton / Mayoral Photo Office )

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now, a follow up on yesterday's reference on the show to align in Mayor Adams' new budget that will expand a program that sends mental health professionals to calls of a mental health crisis rather than police in some cases. How do they decide where the line is? We raised this question yesterday, but couldn't answer it. Between someone who just needs help and someone who's a threat who requires a police presence, sometimes it's a close call. Here's that line again? This is 48 seconds from the mayor's budget address on Tuesday.

Mayor Adams: This budget includes $55 million to expand the B-HEARD program, which stands for Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division. There are teams of EMTs and mental health professionals that respond to 911 calls involving mental health issues. This is not my idea, this is your idea. You told me you needed this and I heard you and we put it in the budget and expanded it. Not every emergency call needs the police. B-HEARD Teams de-escalate tense situations and connect people in crises to the care they need. You know I did something right because Jumaane stood up and applauded me. [laughs]

Brian Lehrer: $55 million for B-HEARD. B-HEARD is a clever acronym for Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division. The city describes this new program as a health-centered response to 911 mental health calls. The boost in funding apparently does have the support of Jumaane Williams who spoke well of it after the Mayor's reference there.

The program has gotten off to a slow start so far and some advocates for people with mental health disabilities have gone frustrated and skeptical about its rollout. We'll talk about that too as well as the growth that the Mayor is now projecting for it. How do authorities decide whether police or mental health professionals are more appropriate to a specific situation? With us for this is our own Matt Katz, WNYC public safety correspondent. Hi, Matt. Always great to have you on.

Matt Katz: Hey there, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you can help us report this story too. Have you called 911 for yourself or for someone experiencing a mental health crisis? How did the police handle that situation or were you met by responders from the city's B-HEARD program? 212-433-WNYC, or you can just ask a question, 212-433-9692. In practice, Matt, how does this work?

Matt Katz: Somebody would call 911, and in the precincts where this program exists, it's currently in parts of Harlem and the South Bronx and it's going to expand to Eastern Queens, Central Brooklyn and the rest of the South Bronx.

Someone calls 911, tells the dispatcher of the situation. If it is what is called a behavioral health call, maybe it's somebody who's intoxicated, maybe somebody is having an anxiety attack or a panic attack, having a verbal dispute with another person, maybe a family member, a psychotic episode, the dispatcher can then send a team of three. There's two EMTs or paramedics and a social worker. These are calls that don't involve the threat of violence. The 911 caller does not say that the person is brandishing a weapon, doesn't say they're making violent threats, is not at risk of harming themselves or others.

They send out these teams and they arrive without flashing lights, they arrive in a vehicle that reads Mental Health Response Unit, and they get out and talk to the individual and try to de-escalate the situation. This started last year, and according to the people who run it, you and I did a story about this for WNYC and Gotham this last month, it's been successful. The way they measure it is hospitalizations.

They said 87% of these individuals were hospitalized when there was a traditional police response, when cops showed up, they then forced these individuals to go to the hospital. When B-HEARD came, less than half led to hospitalizations, which the organizers of this say is a dramatic reduction and very important because hospitalizations are onerous, they take a long time, they don't necessarily help the people long term. If they can de-escalate the situation and connect people to more permanent mental health resources, which is what they do, then they believe that it's a success.

Critics say they responded to something like 20% of the mental health calls and still cops were showing up to the majority of the calls and the precincts where B-HEARD operates. The organizers say they just need to train the 911 responders to better know when to send B-HEARD out instead of the police.

As you know, Brian, this is hugely important. We've seen so much violence by police against mentally ill individuals. We've seen deaths. I spoke to the family of this guy, Eudes Pierre, who in December who had a small pink knife at the Utica Avenue subway in Brooklyn, and the police showed up. I watched the body cam footage of this. If anybody's seen the body cam footage of police responding to a mental health call that ends in violence, you can see that the police are not trained to deal with somebody who's in distress like this.

They never asked this individual's name, they kept their distance because they trying to be safe, but they also clearly were not prepared to handle such a situation. Then the individual is also amped up and reacts aggressively to seeing cops with their guns drawn showing up to supposedly try to help him. It was clear to me that it makes sense to at least try to have a non-cop response to certain calls.

I also went to a training for B-HEARD social workers and EMTs that was held out in Queens, where they went through all the different scenarios. These are people who are trained in dealing with people who have mental health problems. You see individuals come and sit-- The social worker comes in and he sits down. He ask the name. He casually says, "Listen, no police are coming. I just want to know what's going on. Is it okay if the paramedics take your vitals?" It's a much different situation than cops showing up with their guns drawn.

Brian Lehrer: In the Eudes Pierre case, would it have qualified for a B-HEARD team response as opposed to a police response since you say he did have a weapon on him, a small pink knife, as you described it, but nevertheless a weapon?

Matt Katz: That's right. It would not have under this current model because there was a threat of violence. The police actually initially said that Pierre might have called the 911 on himself and that he had left behind a suicide note and therefore was anticipating some violence. Critics say that the program could be adjusted. There are other models in Denver and in Eugene, Oregon in which these non-police responders show up to situations even if there is a threat of violence because they are so equipped to de-escalate the situation. There's been thousands of these calls in those cities that did not result in any violence against the non-police responders.

Advocates for the mentally ill say the police don't really need to show up to these calls. The B-HEARD responders also can call the police for backup. They've only had to do that twice, at least in the period of time where I got stats from the city. New Jersey has a program that they're running, also a pilot program, for state troopers. The state troopers show up to every call, but they supposedly take a little bit of a back seat and let the social workers, the EMTs run the response. There's different models and the Eudes Pierre case, unfortunately, would not have resulted in a non-police response and then ended ended tragically.

Brian Lehrer: Of course, there have been others that have ended tragically. Our listeners may be familiar with names like Deborah Danner, the 66 year old woman killed by police in her home while she was in the midst of a mental health crisis. Saheed Vassell fatally shot by police officers, even though he'd had previous interactions with officers in his precinct and they had classified him as someone with mental illness.

There are these stories that listeners who pay attention to this kind to thing know, and hopefully, these kinds of things will be prevented more as they expand the B-HEARD program. Let's take a phone call. [unintelligible 00:09:45] in Queens has a personal experience to share. [unintelligible 00:09:48] your at WNYC. Thank you so much for calling in.

Speaker 4: Thank you so much for taking my call. About 20 years ago, I was driving my Honda Accord. I do have a mental disability. What happened, it was a snow day, so the car skid out of the road. Some people called 911. When the officer came in, he didn't worry about me, my condition, all what he worried about how to get a case for himself. He said, "Why did you skid out of the road?" I said, "Because of the snow." He said, "Well, open the car for me." He starts to search the car and he find under the carpet in the car Marijuana pipe which has no marijuana, nothing.

This is when I purchased the car, it was in it. I don't know anything about it. He arrested me and he say, "Trace of Marijuana in a pipe.' That destroyed my life worse than it was before. I went worse than person. It can be because I never expected that I would be arrested, I will go through this in my life and my life was changed.

Brian Lehrer: What a terrible story. I think if you can take comfort in something, it's at least maybe in knowing that the laws have changed since then so that you couldn't get arrested and a future person who's in a similar situation couldn't get arrested for that. At least that.

Speaker 4: My son's in the law school now. I feel so guilty of myself that I'm leaving him a bad name after myself for what happened to me.

Brian Lehrer: You're not leaving him a bad name [unintelligible 00:11:36]. You absolutely are not leaving him a bad name. I hope you're okay. Thank you for sharing this with us. Feel good in knowing that this-

Speaker 4: Thank you. I listen to you all the time. This is the best to show I ever listen to in the radio or in the TV. Thank you so much.

Brian Lehrer: Very sweet, and know that you've helped others by telling your story. Oh, well, Matt, that was heart-wrenching.

Matt Katz: Yes. Interactions with police, they have a lasting effect. Police especially in a city where officers have been killed this year, they're responding and prepared for the worst. If there's somebody dealing with a mental health crisis, they literally don't have the training and the expertise in order to figure out what that person is experiencing and how to de-escalate the situation and to avoid violence or arrest or anything that can have a lasting long-time effect on somebody. I think it's really where we are coming to as a country, recognizing that there needs to be alternatives to police responses to all situations.

Brian Lehrer: [unintelligible 00:12:54], one more thought for you, if your son has made it all the way to law school, you are obviously a success.

Matt Katz: Absolutely.

Brian Lehrer: One thing I learned from your story, Matt, is that the B-HEARD program only operates 16 hours a day. Is that simply a quirk of the pilot program or was that part-time availability something the city arrived at strategically?

Matt Katz: Yes, that that's based on funding. There's not unlimited funds, and they say that the majority of the calls for behavioral health issues happen during the day time hours and not in the middle of the night. Critics say you can't have a program like this that doesn't run 24 hours a day because people are having mental health crises at all times, but the city says their stats show that most of the calls come in during the day

Brian Lehrer: Amy in Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Amy.

Amy: Hi, Brian. First time, long time. Just was Calling, listening to your segment. I have a young teenager who suffers with mental illness and there was one instance about a year ago where they were in the street and we were worried that they-- They were threatening to go into the street. They're suicidal and persistently so, and we had to make the very, very hard decision to call 911. It was maybe the hardest thing, one of the hardest things we've done knowing that what that might look like and how scary that might be for them.

The cops and the EMTs came. The EMTs were very, very kind. It was a very scary situation for all the flashing lights and their uniforms for my child. I was hoping that the situation would be de-escalated and we could come back inside and regroup. What they explained was that anytime there's a child who says, "I'm having suicidal thoughts," we have to go to the ER. We ended up going to the ER, which was not uncommon for us and continues to not be uncommon for us, and we came home later that night.

In terms of the B-HEARD, I think the direction is the right one, but I'm very skeptical of, honestly, a program that has any connection to the police. As you've been talking about it's not 24/7, it's like, "Well, here's a step," but are we really committing enough and the right resources to combat this issue?

Brian Lehrer: Amy, thank you. Matt, I think you've heard some skepticism along those lines from some of your sources on your story, right?

Matt Katz: Yes, for sure. They say the fact that the EMTs are part of the FDNY and that this is all routed through 911 makes this too closely associated with law enforcement. They want mental health emergency numbers, specific, not 911. There be another three-digit number to call when somebody's in mental distress. Then that would trigger a non-police response. That's what people want. The caller makes a good point about the flashing lights and the uniforms, those can be triggering things.

The body cam footage from Eudes Pierre, when the incident began in the subway station, he comes out to the street and there were dozens of cars of flashing lights. His family said he had schizophrenia, and that's something that would've been very confusing and overwhelming for him. Advocates want a total non-police response to these things. They say that there are programs elsewhere in the country in which the people who show up, the social workers who show up with khakis and a polo shirt, that they don't get hurt, that they know how to handle these situations, and that if there is a threat of violence, they can always call police backup.

Brian Lehrer: The B-HEARD program being expanded now under Mayor Adams. We'll see if it's rolled out in an effective way over time. There we leave it with Matt Katz, WNYC public safety correspondent. Thanks, Matt.

Matt Katz: Thanks a lot, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.