NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

"WNYC Mobilizes For Harlem Emergency"

On the evening of August 1, 1943, a riot in Harlem reportedly began after a white policeman shot and wounded an African American soldier who had been charged by the officer with interfering in the arrest of a black woman in the lobby of a hotel on West 126th Street. (The audio above dates from August 1). City officials and Harlem civic leaders used WNYC to help quell the violence that followed.

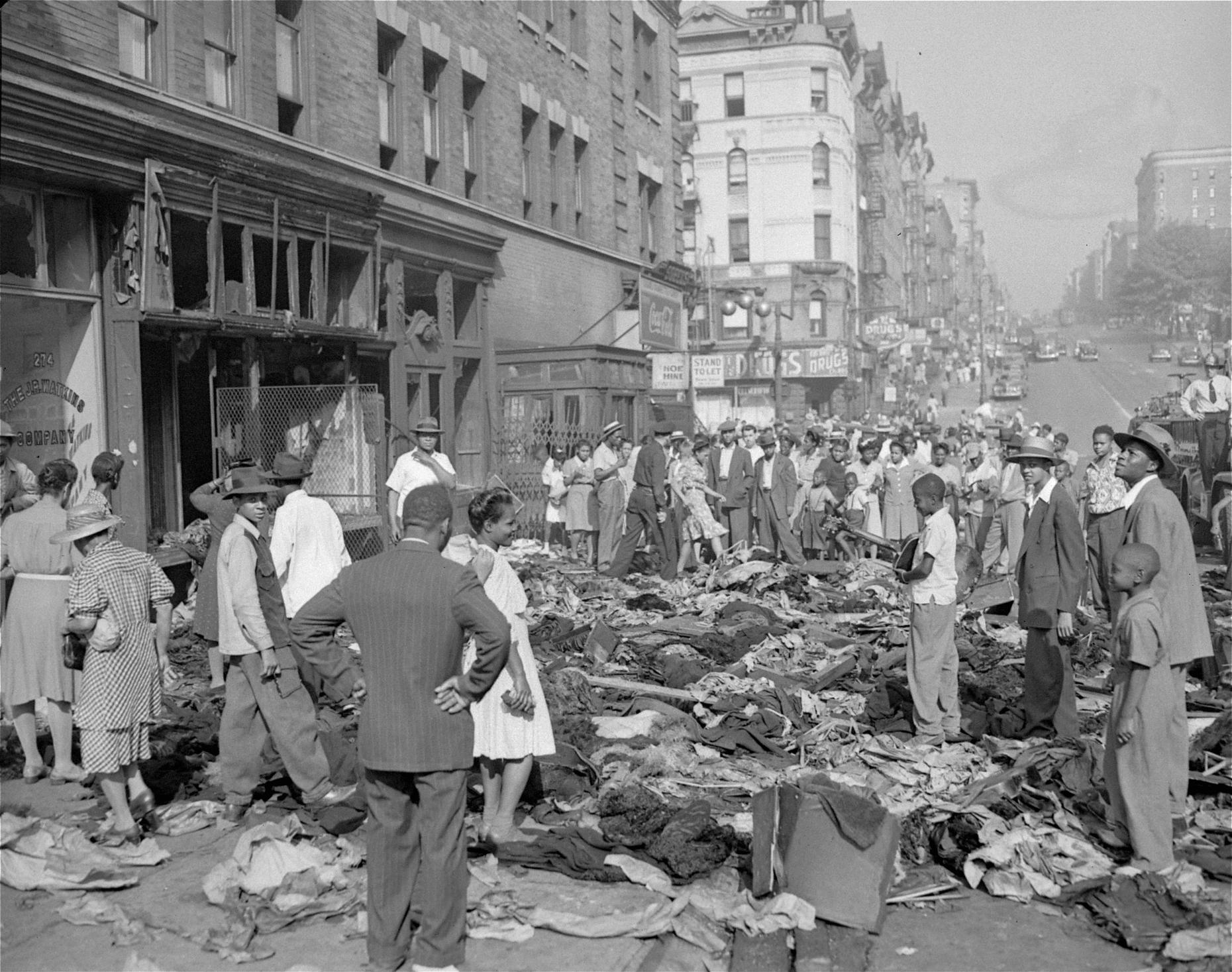

False rumors that the soldier was killed by the officer spread rapidly and provoked an outburst of window smashing, fires, the overturning of cars, and attacks on police. Property damage was estimated at as much as $5 million (1943 dollars). Five hundred people were arrested for rioting, looting, and assault. Five people were killed, and 400 were wounded. The rioting was noted, at the time, as the most violent disturbance in Harlem's history.

Mayor La Guardia imposed a curfew, and 8,000 National Guardsmen were ordered on standby. Leaders of the NAACP, National Urban League, and Councilman Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., praised the police response and said the disturbance was not a race riot but the result of "criminal hoodlum elements." Powell, who would become the neighborhood's Congressman from 1945-1967, blamed the riot on poor economic conditions and "a blind smoldering and unorganized resentment against Jim Crow treatment of Negro men in the armed forces and the unusual high rents and cost of living forced upon the Negroes of Harlem."[1]

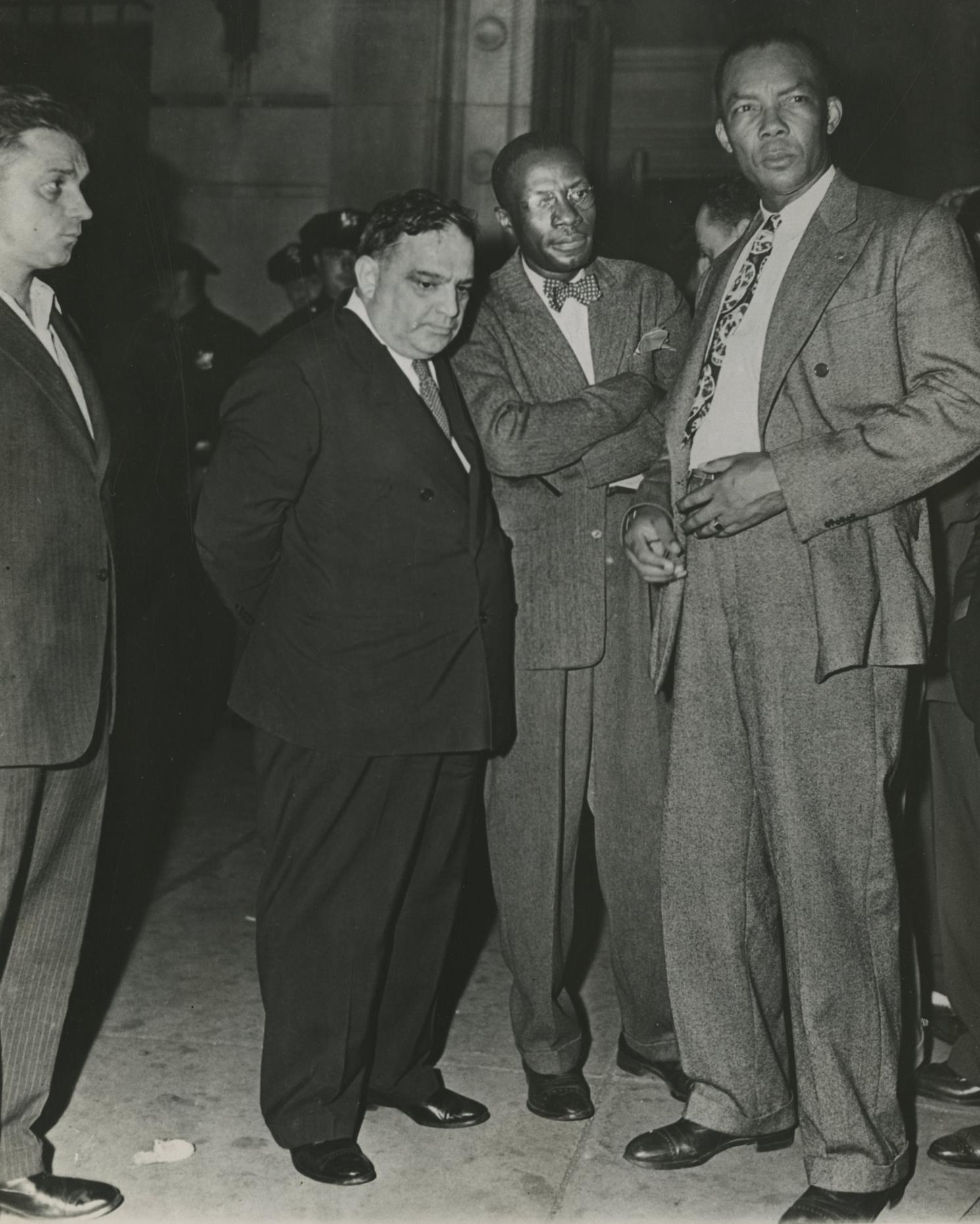

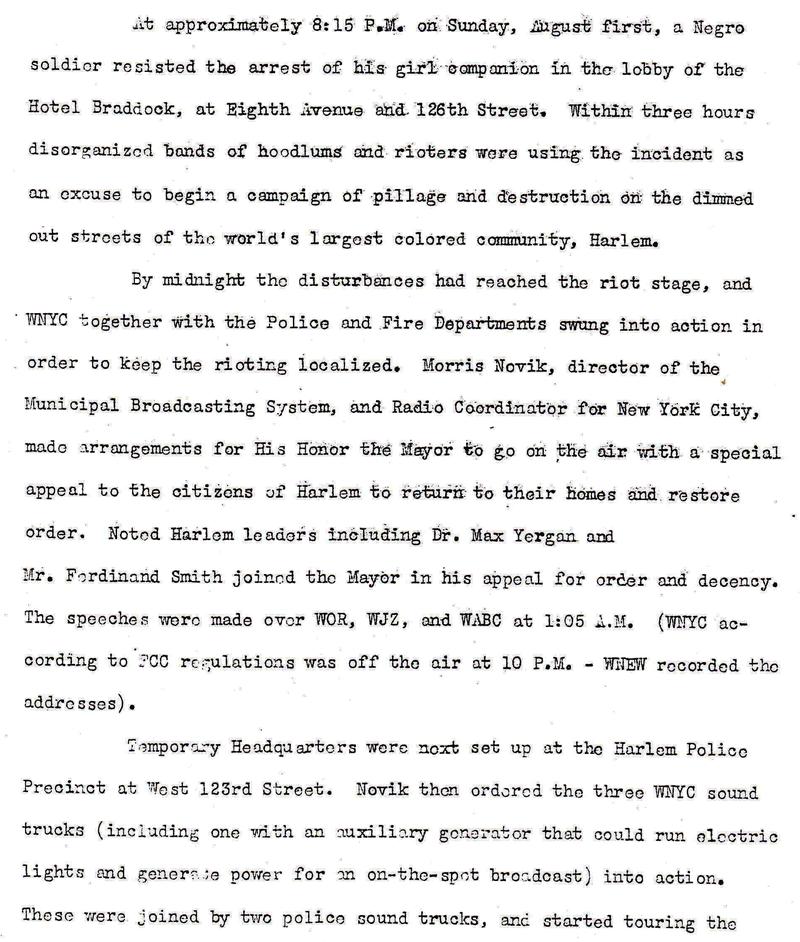

WNYC, the lead station of the city-owned Municipal Broadcasting System, an agency reporting directly to the Mayor, was enlisted in the effort to bring peace to Harlem. A leading goal was to make sure everyone knew the soldier was alive. They also sought to make the Mayor's message, and that of community leaders urging residents to return to the safety of their homes, available to other stations and throughout the streets of Harlem. This was station director Morris Novik's official account.

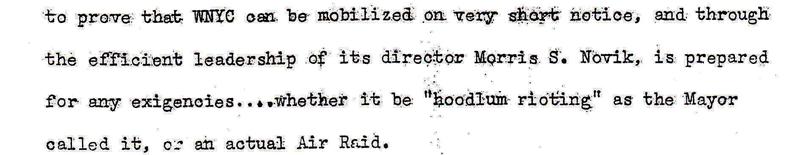

Mayor F. H. La Guardia's August 2, 1943 broadcast over WNYC.

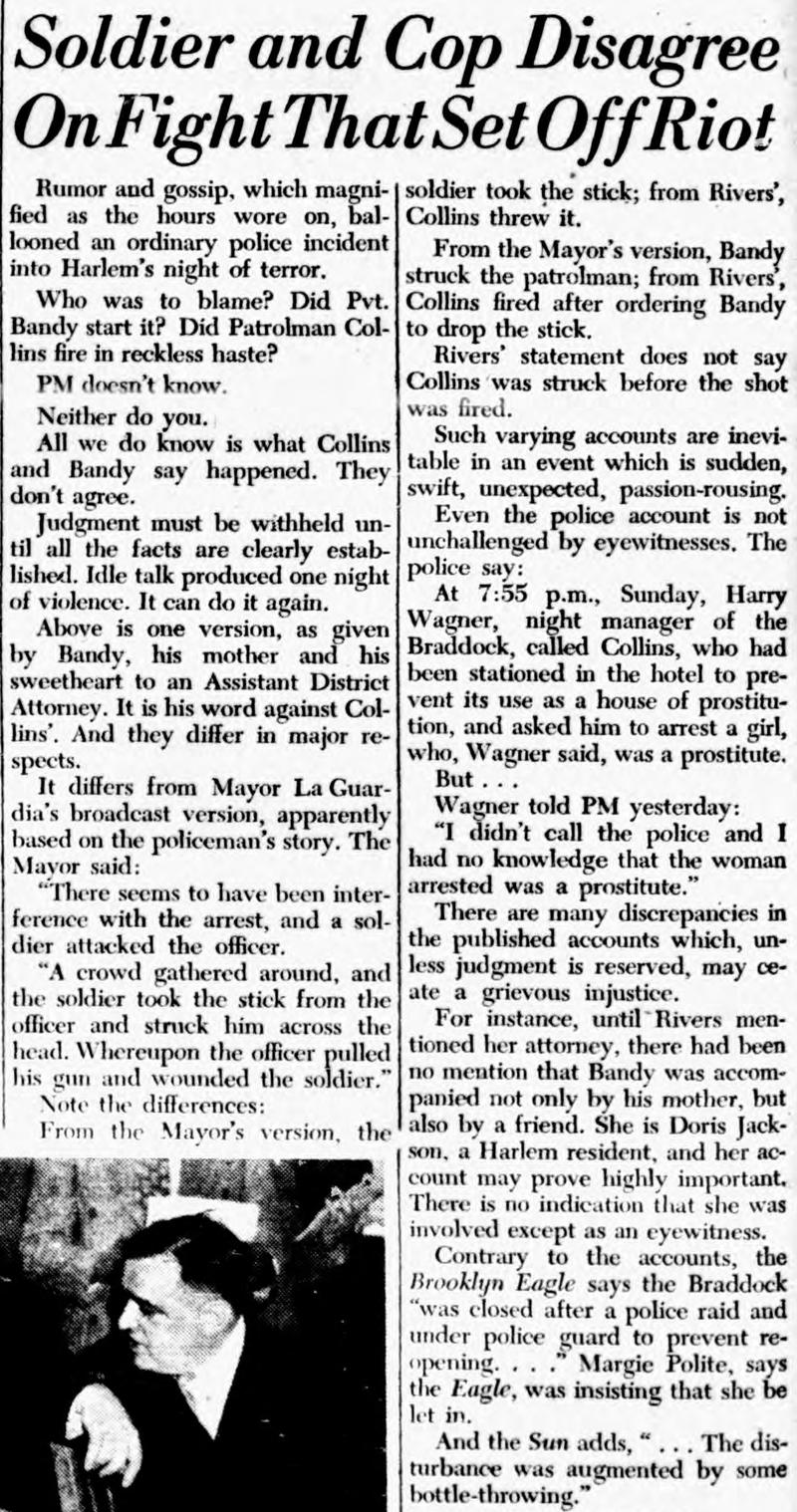

The progressive and ad-free tabloid PM ran the following piece on August 3, 1943 on the incident that ignited the violence.

While the newspaper highlighted Mayor La Guardia's emphasis that the disturbance was not a "race riot," in the sense of blacks fighting whites, "the incidence and underlying causes of the outbreak, however, were racial." Indeed, white-owned businesses (particularly pawnshops and groceries) were targeted in the uprising as the residents of Harlem were all too aware of the contrast between the touted ideals of America and the reality of their daily lives. Their often dire social and economic conditions, especially the job and housing discrimination, revealed the nation's thin veneer of 'freedom and democracy.' The author Ralph Ellison covered the riot for the New York Post[2] and described the rioting largely as revenge.

In the distance there suddenly came the sound of a voice speaking over a loud speaker. Soon we saw a WNYC truck approaching. The speaker, speaking in the name of the Negro Neighborhood Victory Committee, asked the people to return to their homes. He assured them that the soldier had not been killed, and that Mayor La Guardia had promised that fair judgement would be done. The crowd applauded and cheered, then returned to its looting activities...In talking with the people along the sidewalks, I get the impression that they were giving way to resentment over the price of food and other necessities, police brutality, and the general indignities borne by Negro soldiers.[3]

Ellison would revisit the riot as fiction in the final chapter of his 1952 novel, Invisible Man.

'I tell you they mad over what happen to that young fellow, what's his name...'

We were passing a building now and I heard a voice calling frantically, 'Colored store! Colored store!' 'Then put up a sign, motherfouler,' a voice said. 'You probably as rotten as the others.' 'Listen at the bastard. For one time in his life he's glad to be colored,' Scofield said. 'Colored store,' the voice went on automatically.[4]

The prejudice suffered by African Americans at the hands of a nearly all-white police force made the struggle against systemic bigotry worse. And the imposed sacrifices of domestic wartime rationing to support America's military --a military intent on keeping in step with Jim Crow segregation, was more salt in the wound. PM quoted NAACP executive secretary Walter White as saying, "The mistreatment of Negro soldiers is a terribly sore point with Negroes. This is the beginning of the trouble. Had it been a Negro civilian, however prominent, who was shot, there would have been no riot."[5]

The Harlem riot came at a vulnerable time, the mid-point of the United States' involvement in World War II. The event in New York was also not an isolated incident but followed in the wake of the Los Angeles 'Zoot Suit Riots' and race-related disturbances in other American cities that summer. The upheavals threatened morale and cohesiveness on the home front when the country was bogged down in two different theaters of war. Mayor La Guardia and other leaders were keen to do whatever was necessary to 'keep a lid' on African American dissatisfaction and complaints, in light of the critical role played by minority units in supporting white combat troops on the front lines of a strictly segregated military.

Two weeks later, WNYC and other New York stations would begin airing the series, Unity at Home, Victory Abroad, a program urging city residents to take tolerance and unity to heart because prejudice undermines America's efforts to win the war.[7] At the time, many African Americans saw this cooperation with the war effort, both on the home front and in the military, as a proving ground for which their loyalty and willingness to carry on would bring rewards in the post-war period with greater freedoms and less discrimination. The war ended in victory for America and its allied forces in 1945 but, as history has shown, victory's promised rewards for African Americans were few. And seventy-five years after America helped vanquish injustice in Europe and Japan, its fight at home for civil, social, and economic rights rages on.

__________________________________

[1] "Delany and Powell Find High Prices Incite Negroes," The New York Sun, August 2, 1943, pg. 1.

[2] During World War II the New York Post was a liberal newspaper owned by Dorothy Schiff.

[3] Ellison, Ralph, "All of Harlem Was Awake," New York Post, August 2, 1943, reprinted in Reporting Civil Rights, Part One: American Journalism 1941-1963, The Library of America, 2003, pgs. 50-51.

[4] Ellison, Ralph, Invisible Man, Vintage Books edition 1972, pg. 529.

[5] Stewart, Kenneth, "Dewey Orders State Guard to Stand By; Riots Leave Harlem Stores in Shambles," PM, August 3, 1943, pg. 3.

[6] Harold Orlansky's 29-page 1943 study was published in New York by Social Analysis, "a group which seeks to apply the techniques of social anthropology to studies of the contemporary American scene." It is an important piece of work that approaches the event from a holistic perspective. Among the aspects worth noting is his description of the national and local African American press as "agreeing almost unanimously with the white press's analysis" of the disturbance. Only the Amsterdam News and the People's Voice wrote Orlansky, "made an attempt to point out underlying causes." (Page 4 of the study).

[7] The author Arnold Rampersad in The Life of Langston Hughes, Vol. 2 (Oxford University Press, 2002, pgs. 75 & 77) wrote: "…But even more distracting that summer was the rising tension between the races in New York, which itself reflected nationwide unrest, garish against the backdrop of world war, as blacks and whites clashed over Jim Crow. On July 1, Fiorello La Guardia, the Mayor of New York, had written to [Langston] Hughes to ask his help in developing a series of radio programs, 'Unity at Home-Victory Abroad,'* (which would show 'what New York is, how it came into its present being, and why there is no reason that the peace and neighborliness that does exist should ever be disturbed.' The Writers' War Board also wrote Hughes in support of the mayor's campaign, seeking programs that would stress unity, 'so that there will be no danger of race riots in New York.' He agreed to help the mayor and the Board…"

*The Unity At Home-Victory Abroad series aired between August 15th and September 11th of 1943. Seven other New York radio stations took part, and we know that WNYC broadcast, at least, three, (if not more), of the eleven programs.

Special thanks to NYPR's Senior Archivist Daniel Sbardella and to the New York City Municipal Archives vertical files for the WNYC News Release and audio.