NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

The Position of Women in Music

From the February, 1943 WQXR Program Guide:

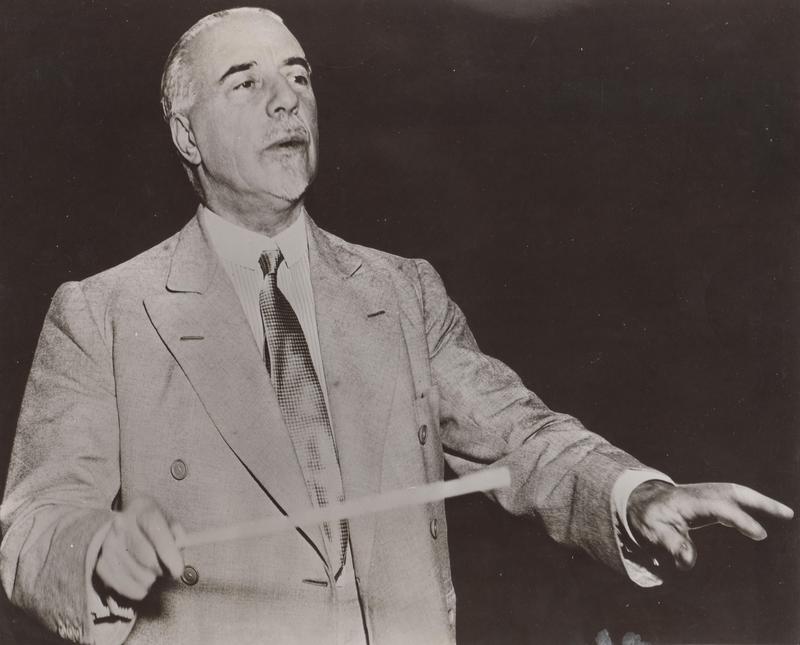

You or we may not agree with everything [or anything] that Sir Thomas Beecham says about women in music, but we know his comments will interest you. This article is condensed from the original which appears in the recently published "Vogue's First Reader." We wish to express our thanks to the publishers for their permission to reprint it.

The number of women in the musical profession has been steadily increasing in the last thirty years or so. As the art of music is in a state of hopeless decadence, this phenomenon is inevitable.

I am, of course, speaking only of the executive side of music. (There are no women composers, never have been and possibly never will be). I look forward with cheerful pessimism to the day when it will be virtually monopolized by women; for man, the more dynamic animal, will not be content much longer to remain in the service of an art which for the moment seems incapable of giving birth to beautiful creations of the imagination.

The simple truth is that all human activity must pass through its periods of rise, ripeness, and decline, and music has been, to a certain extent, fortunate in that it is the last of the great arts in point of date to suffer this general experience. For my part, I look forward to the next twenty years with a quite lively curiosity and anticipation. I want to see what women are going to do with their newest toy, and I believe the results will be full of interest.

There is a definite feminine approach to music which has a distinct pathological value. Women can actually make it sound different to what it is when handled by men. This physical fact I discovered many years ago. Then I heard, during an audition, a number of women play the viola, that most unsatisfactory and nondescript member of the orchestra. The tone produced by these ladies, almost without exception, was wholly unlike that of the masculine candidates, and to my taste more appealing and attractive.

There is a decided feminine element discernible in all the great masters. Much of this I have always felt has been unduly discounted by most male interpreters. Were it otherwise, the world would not have been so grossly affronted as it has been for generations by the ponderous, dull, and graceless performances given almost everywhere of such composers as Bach, Handel, and Haydn. It is high time that a little stress was laid upon the other side of the musical picture, even though we lose something temporarily in the process.

But far more inimical to the fuller development of their powers is marriage. All that can be said is that for artists it takes its rightful place alongside such other major disasters as earthquakes, sea wrecks, battle, and sudden death. And yet there is hardly one among them who, heedless of every other consideration in the world, does not rush into matrimony upon the slightest provocation or the flimsiest pretext.

Scores of times I have viewed the depressing spectacle of some bright young thing of talent, upon whom have been lavished the resources of family or friends and the last word in the expert training of her day, and yet who, upon the very threshold of success, turns up smilingly one day to announce her instant marriage to a man who has sturdily put his foot down against her appearing before the public.

And our soft-hearted, and still more soft-headed modern society, instead of devoting what it elects to call its mind to the discovery of a punishment worthy of such a crime, hails the catastrophe with enthusiasm. It rejoices over the wasted years of useless endeavour.

So far I have spoken only of instrumental or absolute music, in which, up to the present time, my sex has reigned supreme; but, when I come to the vocal branch of the art, the boot is very much on the other foot. Here during the past two hundred years, women have acquired an undoubted ascendancy, mainly because of the invention and development of opera in every land. It was not so, of course, in those earlier days. Then women took no part in public representations of any sort, such a thing being unseemly, unsocial, and unchristian.

In the nineteenth century, who are the greatest singers whose names immediately occur to our memory? Are they men? Hardly ever. Those  whom we think of without effort are Malibran, Jenny Lind, Christine Nilsson, Patti, Melba, Ternina, Eames, and Sembrich; and, in more recent times, Bori, Farrar, Jeritza, Rethberg, and Flagstad. Occasional figures there are among the men, who stand out like solitary stars, much as Maurel, de Reszke, and Caruso. But it is the women who bear off the palm all the time.

whom we think of without effort are Malibran, Jenny Lind, Christine Nilsson, Patti, Melba, Ternina, Eames, and Sembrich; and, in more recent times, Bori, Farrar, Jeritza, Rethberg, and Flagstad. Occasional figures there are among the men, who stand out like solitary stars, much as Maurel, de Reszke, and Caruso. But it is the women who bear off the palm all the time.

Today there is a small chance of this one-sided state of things being varied. For women on the who do not appear to be less gifted and attractive than formerly and decidedly the men are less so. Indeed, the vocal condition of my sex has sunk to a level lower than has been heard for generations, and it might be worthwhile to institute an inquiry into the cause of it.

I do not like, and never will, the association of men and women in orchestras and other instrumental combinations. My beliefs nowadays may be looked upon as heretical or blasphemous. As a conductor, I always find myself cramped and embarrassed by the necessity of imposing upon my critical efforts during rehearsals a chilly politeness which accords ill with the exuberance of my impulses. My spirit is torn all the time between a natural inclination to let myself go and the depressing thought that I must behave like a little gentleman. I have been unable to avoid noticing that the presences of half a dozen good-looking women in the orchestra is a distinctly distracting factor. As a member of the orchestra once said to me, "If she is attractive I can't play with her, and if she is not then I won't."