NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Some Reflections on Rachmaninoff and His Music

The great Russian-born composer, pianist and conductor Sergei Rachmaninoff died at the end of March, 1943 at the age of 70. Charles O'Connell, then RCA Victor's Music Director, composed this personal tribute for the May, 1943 WQXR Program Guide.

Sergei Rachmaninoff was one of the most completely individual personalities I have encountered among artists in the field of music. His every thought and action was dedicated, not merely to music, but to his music. Artistically, he was fiercely egocentric; and in this fact, it seems to me, lies the reason why, though his life span encompassed several distinct musical periods, he was not substantially affected by any one of them. He knew and profoundly admired Tchaikowsky and others among the Russian romantics, but it cannot be established that apart from the racial flavor of the music, he was influenced by them. He had nothing in common with Brahms or Debussy or Strauss; he was a contemporary, but not a modern.

Rachmaninoff was a pessimist. Much has been made of the generally somber character of his music, and it is this quality that has led to the conclusion that he was greatly influenced by Tchaikowsky. I cannot agree. His melancholy was of a philosophical, not a morbid kind. He never felt sorry for himself. He had not --at least prior to the invasion of France--any personal tragedies to mourn. He was grave but not grieving, and often disclosed a healthy cynicism, a wry humor, that were marks of a vital and eupeptic personality. The serious, even the saddest aspects of life engaged his interest; Death itself was a fascinating thing for speculation, but Rachmaninoff's consideration of such subjects was quite detached and impersonal. In years of acquaintance I never heard him laugh, but his rare smile could be more contagious laughter; and his wit, while distinctly dry, was never acid. I have spent many an afternoon with him and [Fritz] Kreisler and their friend of many years, Charles Foley, when after gargantuan servings of pasta and a bottle or two of Chianti, Rachmaninoff would relax in a story-telling mood. His audiences, accustomed to the dour and remote personality of the concert stage, would have been both amazed and entertained; yet the most absurd drollery would be accomplished, on Rachmaninoff's part, by no more than a rather grim yet kindly smile, though Kreisler, Foley and I might be in convulsions.

It is doubtless not the time to attempt any evaluation of Rachmaninoff's music; Time itself will accomplish that. It seems to this observer, however, that the Paganini Variations, of all of Rachmaninoff's works, represents most faithfully the personality of the composer, and his characteristics as a pianist also.

In his recorded repertoire Rachmaninoff left us treasures. Listeners of WQXR must be especially appreciative since this unique station has made and continues to make so much of Mr. Rachmaninoff's music available. Happily, most and the best of his records were made when the techniques of modern sound engineering were fairly well developed. Indeed, his last recording was done with the most modern equipment and technique. It was made only a little more than a year ago. Beautiful as it is, it cannot give a clearer idea of Rachmaninoff as a pianist than several already available recordings. This man had developed technique to an incredible degree of perfection, but I always loved his playing more for its loveliness and variety of tone. Most pianists--and many of the greatest--do not realize the tonal possibilities of the piano, and they are aided and abetted by some scientists who maintain in effect that the players cannot influence the character of piano tone except with respect to its intensity. Rachmaninoff, and a few others, disprove this. He demonstrates in every record that subtle variations of tone quality can be accomplished by pressure, weight, force, pedaling, laxity or rigidity of the fingers and wrists. One of the loveliest illustrations of this occurs in the beginning of the Second Concerto. The eight solemn chords, each individually shaded and colored, yet progressing as a unified phrase and with growing power toward an inevitable climax and response--these glowing yet somber utterances of the piano constitute one of the great exordiums in music.

It is unfortunate that more of Rachmaninoff's songs have not been recorded; indeed, few are sung in concert. They will be. The fame of his Second Symphony, his four concerti, the Paganini Variations, the ubiquitous C-Sharp Minor Prelude, has obscured the many lovely songs he left us. Perhaps the consciousness that he is gone will direct the attention of singers to his songs. His shorter piano pieces, such as the Preludes other than the Prelude Polichinelle, and so on, deserve more attention and, let us hope, will get it.

Rachmaninoff profoundly admired American orchestras, and the Philadelphia Orchestra above all. He considered it incomparably the most beautiful orchestra in the world, and vigorously opposed the recording of his music by any other.

He said, "I used to have Chaliapin in mind in all my composing; now I think only of the Philadelphia Orchestra." The orchestra remembers him, as we all do, with respect and affection.

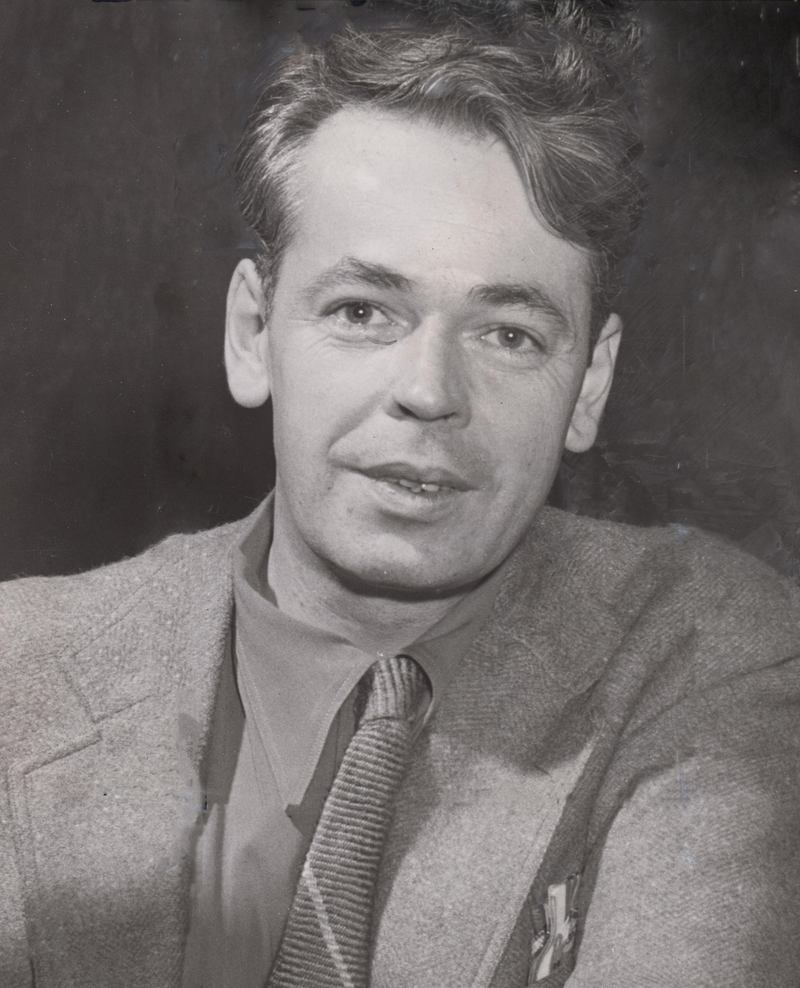

Rachmaninoff at a Steinway grand piano in 1936 or earlier. (Wikimedia Commons)

Charles O'Connell was a conductor, recording executive and arranger. From 1930 to 1944 he was head of the artist and repertoire department of the RCA Victor Red Seal label, then music director of Columbia Masterworks (1944-1947). He published The Victor Book of the Symphony (1934; new edition, 1948); The Victor Book of the Opera (1937); The Other Side of the Record (1947); The Victor Book of Overtures, Tone Poems and Other Orchestral Works (1950).