It Worked in Theory: Richard Nixon on Strategy in South Vietnam, 1966

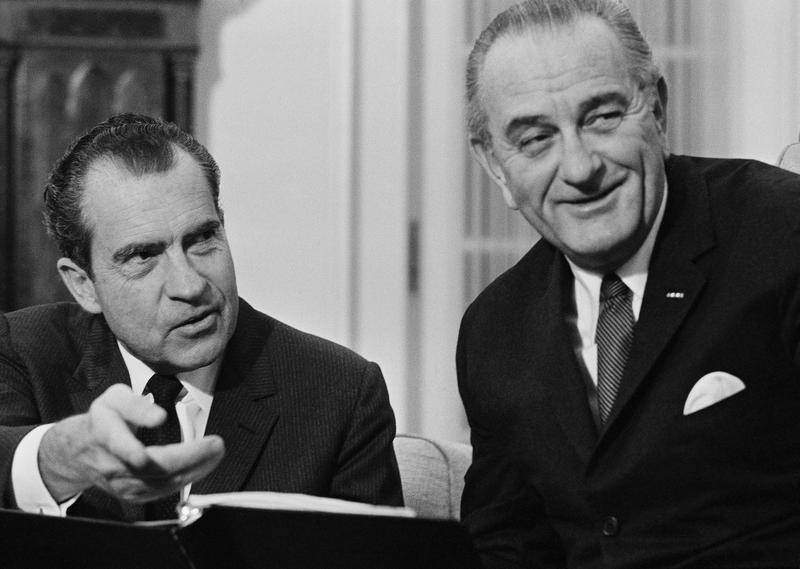

Richard M. Nixon chooses this 1966 appearance at the Overseas Press Club to lay out his position on Vietnam, but not before amiably ribbing Democrats and the press.

After a boisterous introduction by the journalist Victor Riesel, Nixon explains why he has chosen to tackle the difficult and divisive subject of Vietnam, instead of just letting the current Democratic administration "stew" in its own dilemma. There are three reasons: to address a lack of accurate information, which leaves the public puzzled as to what we are doing there; because Hanoi is looking for signs of divisiveness in the upcoming election, the "loyal opposition" must make clear where it stands; and, finally, because people in this country must not just support a policy solely out of patriotism but from a genuine understanding of the situation.

Nixon is careful not to attack the Johnson administration directly, prefacing his remarks by saying, "Great policy is the direct result of competition of two relatively equal parties." He warns that though this is the most "difficult," "unpopular," and "misunderstood" war in American history, "it is also the most important," for its outcome will determine whether or not we will prevent World War III. China's aim, he insists, is to dominate the Indo-Chinese peninsula. If it can prolong the war long enough, it will reach a sufficient nuclear capability to use atomic weapons in the region. In order to avoid South Vietnam "falling like a ripe plum" into Chinese hands, we may very well then be forced to match their heightened aggression with our own nuclear arsenal, leading to an all-out war. How do we avoid this? He dismisses vague calls to alleviate poverty in the region or to strengthen the South Vietnamese democratic institutions as well-intentioned but too slow. He calls for a moderate increase in U.S. forces (but not so much as to make it appear that South Vietnam is not fighting its own battles), continued bombing of the North, and a type of "economic quarantine," punishing countries who persist in aiding North Vietnam.

On the diplomatic front, in any negotiations, he says he would not cede any territory or allow the formation of any coalition government that included the North Vietnamese. As for propaganda, he advocates a push for a "united United States," recommending the conflict be referred to as "The War to Keep the Pacific From Becoming a Red Sea." In concluding, he predicts that if these measures are followed, in 25 years, Vietnam will be seen as "America's finest hour." During the ensuing question period, Nixon dodges inferences about his own prospective candidacy for president, and defends then-Senate candidate Mark Hatfield who, though running as a Republican, had voiced doubts about continued American involvement in Southeast Asia.

Nixon was born in 1913. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, in 1947. In Congress, he made a name for himself as an anti-Communist by his sharp questioning of suspected Soviet spy Alger Hiss during a session of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Nixon's less "gentlemanly" style marked him as a new breed of Republican, as was evidenced in his next campaign, described by the website biography.com:

In 1950, Nixon successfully ran for the U.S. Senate against Democratic Rep. Helen Gahagan Douglas. She had been an outspoken opponent of the anti-Communist scare and the actions of the HUAAC. Employing previous campaign tactics, Nixon’s people distributed flyers on pink paper unfairly distorting Douglas's voting record as left-wing. The Independent Review, a small Southern California newspaper, nicknamed Nixon “Tricky Dick,” a derogatory nickname that would remain with him for the rest of this life.

After a brief Senate career, Nixon was chosen to be Dwight D. Eisenhower's vice-presidential nominee. He served as vice president for eight years, taking many trips and establishing strong credentials in foreign policy. In 1960, he lost the presidential election to John F. Kennedy. After an unsuccessful run for governor of California, he ostensibly retired from politics. But as the statesmanlike tenor of this foreign policy performance makes clear, by 1966 he was already contemplating another run for the presidency. Two years later, he was elected president. After being re-elected by an overwhelming majority in 1972, however, he became enmeshed in the Watergate scandal, which brought to light many unsavory aspects of his administration and forced him to resign. This event was traumatic not just for its protagonist, but for the nation as a whole. Political reporter R.W. Apple noted:

Mr. Nixon was driven from office by the Watergate scandal, resigning in the face of certain impeachment on Aug. 9, 1974. He often acknowledged that the event would inevitably stain his pages in history, and despite strenuous and partly successful efforts over two decades to rehabilitate his reputation, he was right. It was a spot that would come not out. He never completely dispelled the sense of shame that clung to his last days in the White House. In some ways, American politics has never fully recovered, either. The break-in at the offices of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex in Washington on June 17, 1972, and the frenzied, protracted efforts to cover it up, helped to convince many Americans that they could not trust their government.

Nixon's character fascinated the American public. This press conference speech typifies many of the contradictions he embodied. He forcefully condemns those who would "cut and run" in Vietnam, yet critics maintain that as president that is precisely what he went on to do. He goes to great lengths to portray Republicans as "the loyal opposition," yet once in office his partisanship eventually led to the Watergate break-in, the burgling of Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, and the infamous "enemies list." He jokes with and seemingly charms the press which he then went to extraordinary lengths to deceive and, in the case of certain reporters and newscasters, carry on personal vendettas against. As the Oxford Dictionary of Political Biography concludes:

Nixon was one of the most controversial presidents in the 20th century and the only one in history to resign. He adopted an adversarial approach and attracted the enmity of a great many opponents. He was shy and insecure, affected by the death of two of his brothers while still young, and awkward in his dealings with others. He was keen to win and adopted tactics that facilitated his winning. Towards the end of his presidency, he adopted a siege mentality. He was a man driven from within. Life was seen in terms of a series of crises — hence the title of his book, Six Crises — and he had an inherent tendency to rigidify. Watergate was the occasion when he rigidified and consequently sacrificed the presidency.

Nixon died in 1994, at the age of 81.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.