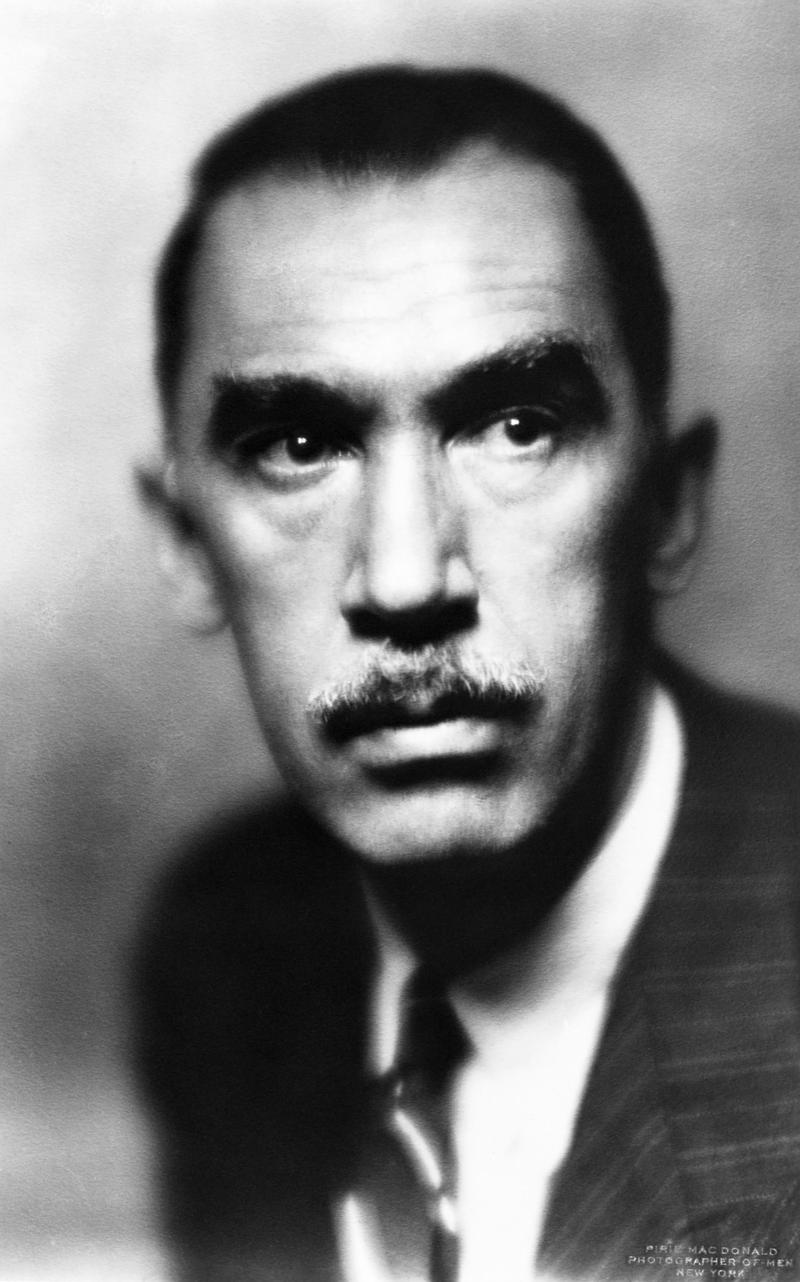

Robert Sherwood Humanizes Wartime Efforts and Urges 'Enduring Peace'

Calling himself a "Broadway wise-cracker and a Hollywood hack," Robert Sherwood, author, soldier, pacifist, and speechwriter, gives a stirring account of his wartime work for the Roosevelt administration at this 1948 Books and Authors Luncheon.

As a writer, he was credited with adding touches of humor to the president's speeches (though he denies having come up with the famous reference to FDR's dog, Fala). As director of the Office of War Information, he traveled to Europe and the Pacific, where the heroic soldiers he met were "not exceptional but representative of the extraordinary character and courage and determination of our people." Quoting Santayana, he urges America not to repeat the "hideous mistake" it made after World War I and reminds the audience that "there is nothing this nation cannot achieve including enduring peace."

Sherwood is promoting his book, Roosevelt and Hopkins (1948), but in typical self-deprecating manner barely mentions it, preferring to dwell on the people in government who ran the war and the soldiers on the ground who fought it. A former pacifist, he seems to be warning against the rising Cold War sentiment that would soon become the hallmark of U.S. foreign policy, even quoting some friendly words of Stalin's at the recent Tehran Conference. He also has kind words for his fellow author on the dais, the Broadway personality Billy Rose. One is left with the impression of an extremely nice but very private man.

Sherwood was born in 1896. After graduating from Harvard University, he fought for the Black Watch regiment of Canada in World War I. Sherwood's war experiences (he was gassed while in the trenches) made him an ardent pacifist. In New York, he became one of the first movie critics, writing for Vanity Fair and Life, and was a member of the celebrated Algonquin Round Table along with such wits as Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley. His own dramatic career, starting with the "Road to Rome" (1927), was extremely successful, featuring plays with strong moral and often antiwar themes that somehow managed to be crowd-pleasers as well. He won the Pulitzer Prize for drama three times. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes how:

The heroes of "The Petrified Forest" (1935) and "Idiot’s Delight" (1936) begin as detached cynics but recognize their own bankruptcy and sacrifice themselves for their fellow men. In "Abe Lincoln in Illinois" (1939) and "There Shall Be No Night" (1941), in which his pacifist heroes decide to fight, Sherwood’s thesis is that only by losing his life for others can a man make his own life significant.

Much of his work in Hollywood was uncredited, although he had several successful collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, notably "Rebecca" (1940). He also adapted several of his own plays for film.

As with many pacifists of the 1920s and 1930s, the rise of Fascism caused Sherwood to reconsider his beliefs. His insider's view of the Roosevelt administration during his time as speechwriter prompted him to write the book he is publicizing in this talk, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1946), which details the unique relationship Roosevelt had with Harry Hopkins, his longtime aide and unofficial "national security adviser." The book, despite Sherwood's lack of training as a historian, was both a popular and critical triumph, winning him both a fourth Pulitzer and the prestigious Bancroft Prize. It was republished as recently as 2002, at which time no less a magazine than Foreign Affairs said that he:

…wrote his book with astonishing access to relevant people and papers. This book focuses on the war years, using Hopkins as the best window through which to see the inner workings of global leadership. Despite his empathies, Sherwood was a rigorous historian and brilliant portraitist. In this current era of uncertainty and opportunity, Sherwood's book strongly, subtly resonates.

After the war, though in ill health, Sherwood had one last success, writing the script for William Wyler's film "The Best Years of Our Lives" (1946), chronicling of the return of three service veterans and how they adjust, or fail to adjust, to life in peacetime. This won him the Oscar for best screenplay.

In a tribute to Sherwood, his fellow playwright Elmer Rice suggested that:

Throughout his work — vivid and diversified as it is — there runs one dominant theme: the reluctance of the self-centered sensual man to assume the responsibilities that life thrusts upon him, and his ultimate recognition of the moral obligation to do what must be done.

Sherwood died in 1955, at the age of 59.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

Note: Some poor audio quality due to condition of original recording.