Whitney Young Provides Depth and Texture to Portrait of Racial Inequality

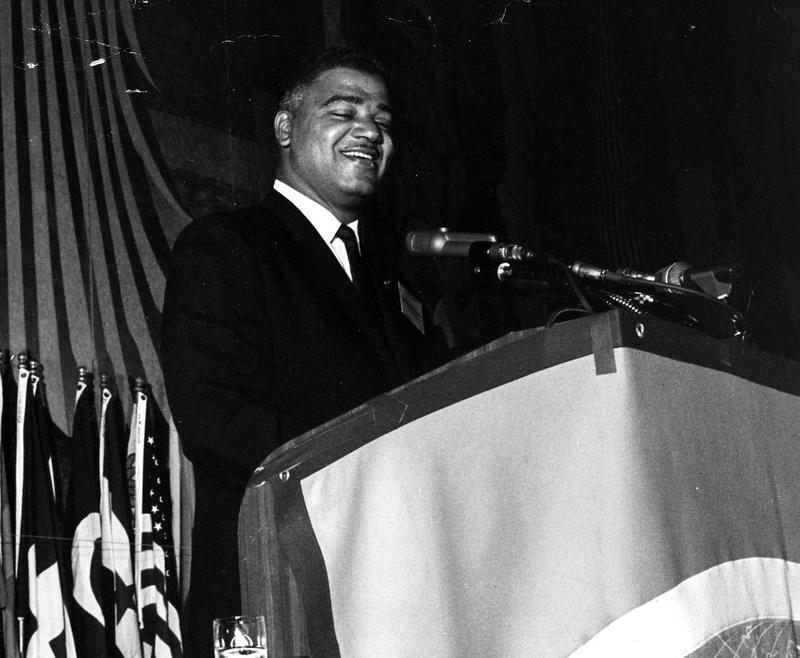

Focused, uncompromising, and yet essentially pragmatic, Whitney Young, executive director of the National Urban League, answers questions at this 1966 meeting of the Overseas Press Club.

Young was one of the most powerful voices calling for achieving racial equality by working within the system. His tragic death five years later coincided with the rise of a different type of black leader, and a different type of civil rights movement.

Just back from Vietnam, he weighs in on the plight of blacks in the military, as well as on many domestic issues, including the soon-to-be-built World Trade Center, the War on Poverty, the Black Power movement, and the disturbing phenomenon of urban riots. Young starts by lambasting the anti-busing demonstrations in Boston and elsewhere, attributing them to the protestors' insecurity. "They believe they're superior to the Negro. That's their only claim to fame." As for Vietnam, he avoids commenting on the war directly, emphasizing (with considerable eloquence) how black soldiers are being allowed to prove themselves in the Army as they are not allowed to prove themselves back home. Yet all the press talks about are the negative aspects of the war. He calls for the World Trade Center to be built in Harlem, to revitalize a neighborhood where "even the houses of prostitution have moved downtown." He is most scathing about "Black Power," a slogan he finds incomprehensible. Money and education confer power, not skin color. During the question period he scoffs at accusations that Communists are behind the recent race riots. "No mother whose child's toe has been bitten by a rat needs Mao or Castro…to come over and say, 'Your child has been bitten by a rat.' " He rejects the increasingly apocalyptic tone of some black leaders, concluding, "white society may collapse…because of its moral bankruptcy, but I can't plan a program waiting on that."

Young was born in 1921. His father was the principal of a black boarding school and his mother was the first black postmistress in the state of Kentucky. From an early age, Young showed striking organizational skills. He trained both as an electrical engineer and as a social worker. By 1961, had become executive director of the National Urban League. Taking over a cautious, some would say moribund, institution, Young energized it. As the organization's website recounts:

…he substantially expanded the League's fund-raising ability and, most critically, made the League a full partner in the civil rights movement. Although the League's tax-exempt status barred it from protest activities, it hosted at its New York headquarters the planning meetings of A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., and other civil rights leaders for the 1963 March on Washington. Young was also a forceful advocate for greater government and private-sector efforts to eradicate poverty. His call for a domestic Marshall Plan, a 10-point program designed to close the huge social and economic gap between black and white Americans, significantly influenced the discussion of the Johnson administration's War on Poverty legislation.

Young represented a less radical but no less determined wing of the civil rights movement. The Urban League's emphasis was on gaining blacks equal opportunity in the workplace, in education, and in housing. This resolve to advance by peaceful means often set him in unwilling opposition to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. One can hear, in this press conference, Young walking a tightrope, not criticizing Johnson's Vietnam policy (which King recently had), while trying to bend the conversation toward the plight of the black soldier and black veteran. One also glimpses how he and other "first generation" civil rights leaders would soon be overtaken by the Black Power movement of the later 1960s. Young's incomprehension at the press coverage given to what he sees as a small, half-baked group more interested in street theater than tangible political gains is made even more explicit by this comment about the slogan's inventor, Stokely Carmichael:

"Anyone can arouse the poor, the despairing, the helpless. That's no trick. Sure they'll shout 'black power,' but why doesn't the mass media find out how many of those people will follow those leaders to a separate state or back to Africa?"

But the more extreme approach, particularly after King's assassination in 1968, would increasingly become the public "face" of the movement. One sees in Young's career a path not taken, or at least not sufficiently publicized, in the black struggle for equality. Yet his achievements were, by any means of calculating, impressive. The Gale Encyclopedia of Biography reports:

Young saw his role as one of trying to maintain contacts and liaison between increasingly polarizing white and black groups in American society. He admonished black civil rights protesters against violence and at the same time warned white decision makers that, unless substantial gains were made, violence from blacks could be expected, if not condoned. Under Young's leadership, the National Urban League received grants from government and private sources to work on such projects as job training, open housing, minority executive recruitment, and "street academies" (schools in ghetto communities for students who have dropped out of regular school).

Whether reason alone would have ever been enough to force white America to acknowledge the unique dilemma blacks faced is still a question open to historical debate. It was not one Young would live to see resolved. In 1971, attending a conference in Lagos, Nigeria, Young drowned while swimming with friends. He was 49.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.