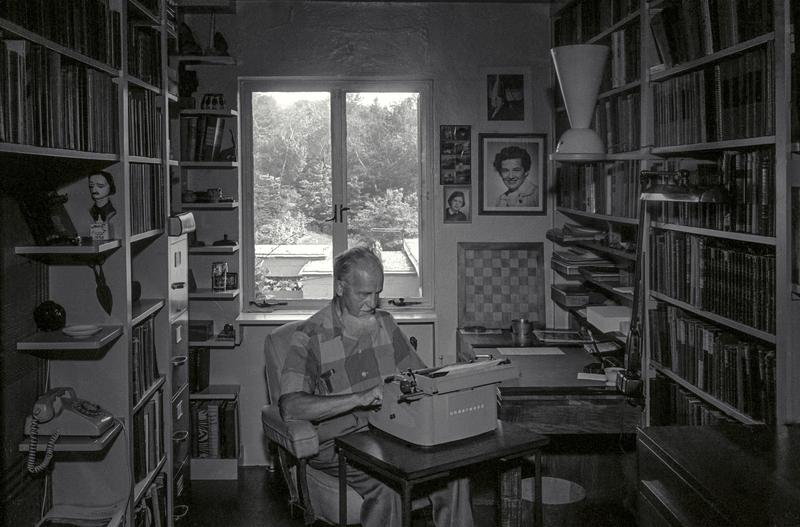

Rex Stout Writes Detective Stories, Makes Enemies of the FBI

Rex Stout, the creator of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, addresses the audience at this 1966 Books and Authors Luncheon as if they were his "Committee on Grievances."

First, he outlines his career as a writer. Five years were spent saying "serious things." This got him a few nice letters and a few good reviews but not much else. Then he "decided just to write stories," by which he means detective stories featuring his famous duo of Wolfe, the portly genius, and Goodwin, his more mobile sidekick. This provided him with money and recognition, as well as having the distinction of having written the only mystery story to be translated into Sinhalese. For his latest book, The Doorbell Rang (1966), he decided to take on the FBI, not out of any political motive, he blandly insists, but because it would be "fun to use them as opponents."

His tongue-in-cheek grievance consists of complaining that the ensuing hoopla, which he had initially hoped was due to his having written a really good story, instead turns out to be "because I'd had the nerve to poke J. Edgar Hoover in the nose." Stout protests he had no such intention, although he then slips in, "I think that J. Edgar Hoover is one of the most objectionable people in our country today." Perhaps, he ruminates aloud, he should give up trying to write good stories and become a professional crusader, "taking on" various organizations. He then provides a list of possible targets: the Salvation Army, the Roman-Catholic hierarchy, the Boy Scouts, the John Birch Society, the Ku Klux Klan, or the Women's Christian Temperance League. The audience, listening to this eccentric litany, alternately applauds and laughs nervously.

Born in 1886, Stout was recognized early on for his exceptional qualities. As the Kansas Historical Society recounts:

Before his seventh birthday, young Rex had read all 1,200 books in his father's library, which included the Encyclopedia Britannica and the Holy Bible. Young Rex…was short of stature but long on brains. He took delight in correcting his teachers or challenging them to furnish proof of certain statements, which hardly endeared him to teachers. Stout's biographer, John McAleer of Boston College, dubbed his subject during his high school years, 1899-1903, as "Mr. Know-It-All in Knee Pants."

After high school, Stout enlisted in the Navy, where he spent two years as a crewman on Theodore Roosevelt's yacht. Determined to write, he held a series of other jobs before coming up with the idea of school banking, in which young students were encouraged to open small accounts in order to learn the value of savings as well as to familiarize themselves with the banking system. This made him a rich man and enabled him to move to Paris, where he spent the next five years writing books that received some critical recognition but were not best-sellers. After the Depression wiped out much of his savings, he returned to the United States and published mystery novels. These invariably featured his two famous creations: Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin. As the St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture puts it:

Wolfe and Goodwin quickly endeared themselves to readers not only for their adeptness at solving crimes but for their trenchant comments on American life, war, big business, and politics. Nero Wolfe, the puffing, grunting, Montenegrin-born heavyweight gumshoe with a fondness for food and orchid-growing, made his appearance in 1934 with the publication of Fer de Lance. A steady stream of Nero Wolfe books followed, to the point where the character became more well-known than its creator. Often compared by literary critics to Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, Wolfe and Archie played complementary roles in Stout's fiction. Detective work for Wolfe was a business, and his clients were charged handsomely for his services, allowing the investigator to indulge his penchant for orchids and food. Goodwin, like Watson, is the legman, the hardboiled detective who satirically narrates the events in the story. He is dispatched to do all the detecting that Wolfe, the consummate detective, refuses to do. Wolfe is portrayed by his partner as partly human, partly godlike, with an arrogant intelligence, a gourmand's appetite, and an orchid grower extraordinaire. Goodwin treats clients, cops, women, and murderers with the same degree of wit and reality he applies to Wolfe. Singly they would be engaging but together they form a brilliant partnership that brought a new, humorous touch to detective fiction.

Stout became a public figure during World War II, when he emerged as a virulent anti-Hitler and anti-German propagandist. After the war he lobbied for a "hard peace," to punish the Germans and prevent future wars. He then took up the cause of nuclear disarmament, becoming active in the United World Federalists. During the Red Scare of the 1950s, he ignored a subpoena from the House Un-American Activities Committee. Yet as the list of potential "targets" he presents at the end of this talk illustrates, his political interests were hard to pigeonhole. While he deplored what he saw as the FBI's assault on civil rights, he also alienated many on the left with his decidedly hawkish views on America's military involvement in Vietnam.

An interesting underlying tension in Stout's performance at this luncheon is his still apparent annoyance at having achieved wealth and fame in a genre of writing not seriously regarded by most critics, that he is in the news not because he wrote a "good story" but because he took on the FBI. This uneasy gap between popular culture and literature is perfectly caught in the tone of Stout's New York Times obituary, which characterizes him as "…a wiry, goat-bearded, argumentative, intense, immodest, highly talented artisan." The implications of that last word might account for the above-cited "grievance" he felt compelled to air.

Stout died in 1975 at the age of 88.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.