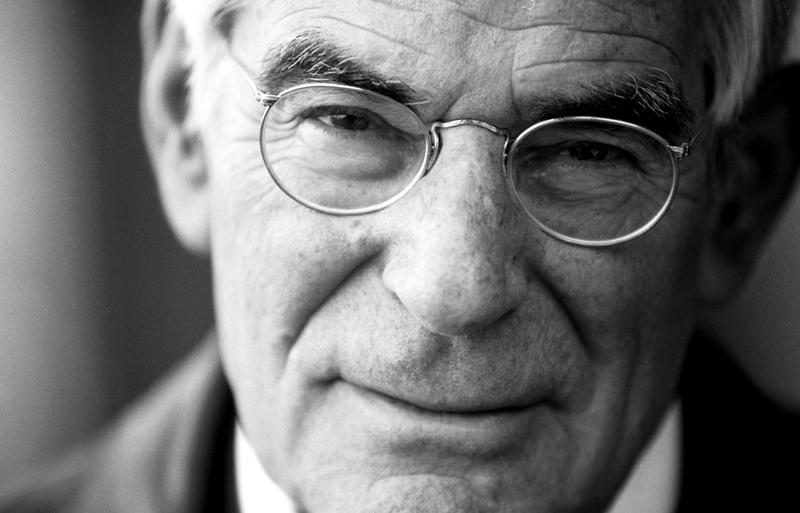

Foreign Correspondent David Halberstam Analyzes Conflict in Vietnam

David Halberstam briefs this 1964 meeting of the Overseas Press Club on what he sees as a "sharp conflict" between America's official optimism and the reality experienced by reporters embedded in Vietnam.

A new breed of reporter (at 29, he had just taken over from legendary Homer Bigart of The New York Times), Halberstam notes that the foreign correspondent's role has changed since the days when he would arrive in a country and get relatively dispassionate, detached views of the situation from various U.S. officials. In Vietnam, he says, missteps can be traced back to the 1961 Taylor Report, which recommended a build-up of "advisers" and helicopters. U.S. officials now feel "deeply" involved. But when talking to troops on the ground, staying for a week at a time with a unit rather than just coming in for one-day guided junkets, Halberstam says, he found that the general sense of the war was that we were "fighting it in a very superficial sense."

Taking questions, many of which refer to the recent Buddhist crisis involving government repression of a Buddhist-led movement of civil resistance, he argues that the conflict is not between Catholics and Buddhists but between "the government and most of the population." Asked if the new military junta shows any signs of conducting the war more successfully than the previous government, he says his contacts in the State Department think yes, but that he's pessimistic. "It's a pretty eroded situation." He recounts several attempts at minor harassment of the press but considers them "part of the game." Talking to soldiers on the ground, though, he found "Americans are pretty honest people." He concludes by saying that, above all the political or religious considerations, what's important to remember is that the people of Vietnam are tired of being at war -- which they have been since 1946.

The journalist Irene Kuhn (1898-1995), who is sharing the stage with Halberstam, is asked the final question, "What advice would she give to aspiring journalists?" "A general education. Learning additional languages." She then adds, "And keep your imagination dry."

Born in 1934, Halberstam came to Vietnam after reporting on the civil rights movement for a small Mississippi newspaper, and then covering the conflict in the Congo. These proved to be excellent preparations for the task that awaited him in Southeast Asia. A self-professed "cold war child," Halberstam did not arrive with a predetermined agenda, but also refused take on blind faith the overly optimistic view of the war being pushed by the Pentagon and State Department. As The New York Times summarized:

…his reporting, along with that of several colleagues, left little doubt that a corrupt South Vietnamese government supported by the United States was no match for Communist guerrillas and their North Vietnamese allies. His dispatches infuriated American military commanders and policy makers in Washington, but they accurately reflected the realities on the ground. For that work, Mr. Halberstam shared a Pulitzer Prize in 1964. Eight years later…he chronicled what went wrong in Vietnam -- how able and dedicated men propelled the United States into a war later deemed unwinnable -- in a book whose title entered the language: The Best and the Brightest.

As some of the anecdotes in this talk illustrate, Halberstam's attitude and approach were radically different from the generation of war correspondent that had preceded him. The impression his reporting made was so great that President Kennedy pointedly suggested to The Times publisher that he be replaced. George Packer, writing in The New Yorker, recalled:

Halberstam’s wartime work will last not just because of its quality and its importance but because it established a new mode of journalism, one with which Americans are now so familiar that it’s difficult to remember that someone had to invent it. The notion of the reporter as fearless truth-teller has become a narcissistic cliché that fits fewer practitioners than would like to claim it. “David changed war reporting forever,” Richard Holbrooke, who had known him in Vietnam, said last week. “He made it not only possible but even romantic to write that your own side was misleading the public about how the war was going. But everything depended on David getting it right, and he did.”

After leaving The Times in the late 1960s, Halberstam devoted the rest of his life to writing books that often seem to straddle the line between history and journalism. Behind them all, though, is an autobiographical component. The Best and the Brightest (1972) asks the question how the greatest minds in the country could lead his generation down such a disastrous path. Other topics had similar personal connections. As the British magazine The Economist pointed out:

The school of literature he belonged to was quintessentially American. He produced, for the most part, very big books on very wide themes: the media and politics in The Powers That Be (1979), foreign policy in War in a Time of Peace (2001), past and future ages in The Fifties (1993) and The Next Century (1991). A Halberstam paragraph usually filled a page, unfolding portentously toward some great quotation that glimmered in the final line. Between the doorstoppers came books on sports, allegedly lighter relief for him. But sports, especially baseball, were also mirrors of the cultural changes he felt appointed to record. October 1964 (1994) became a treatise on civil rights as seen in team changing-rooms; Playing for Keeps (1999), about Michael Jordan, turned into a book about the modern worship of celebrity; Summer of '49 (1989), in which the Yankees and the Red Sox strove for the pennant, was an elegy for the world Mr. Halberstam seemed most to hanker after, where travel was by train and entertainment on the radio, and where the afternoon sun shone quietly on baseball played on grass.

Halberstam was killed in an automobile accident while being driven to an interview he had scheduled with the famous quarterback Y.A. Tittle in 2007. He was 73.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.