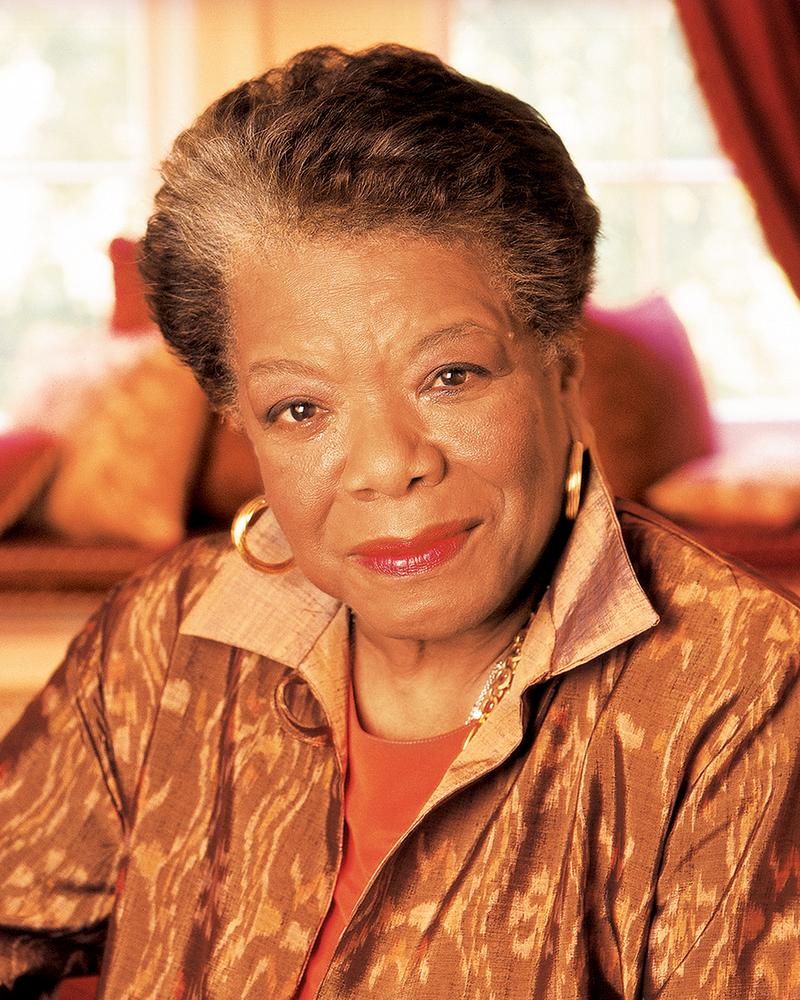

Update: Maya Angelou died on May 28, 2014. This interview first aired live on April 2, 2013. An edited version was rebroadcast as part of a best-of episode on September 2, 2013 for Labor Day, and was rebroadcast again on May 28, 2014.

Maya Angelou, poet, writer, activist, author of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and now, Mom & Me & Mom (Random House, 2013), tells the story of her relationship with her mother and her mother's decision to leave her to be raised by her grandmother.

.@drmayaangelou says she loves all art forms, but "I yearn for poetry." She calls Edgar Allen Poe "eep." wny.cc/10uLFdh

— Brian Lehrer Show (@BrianLehrer) April 2, 2013

Excerpt: Maya Angelou's MOM & ME & MOM

The first decade of the twentieth century was not a great time to be born black and poor and female in St. Louis, Missouri, but Vivian Baxter was born black and poor, to black and poor parents. Later she would grow up and be called beautiful. As a grown woman she would be known as the butter-colored lady with the blowback hair.

Her father, a Trinidadian with a heavy Caribbean accent, had jumped from a banana boat in Tampa, Florida, and evaded immigration agents successfully all his life. He spoke often and loudly with pride at being an American citizen. No one explained to him that simply wanting to be a citizen was not enough to make him one.

Contrasting with her father’s dark chocolate complexion, her mother was light-colored enough to pass for white. She was called an octoroon, meaning that she had one-eighth Negro blood. Her hair was long and straight. At the kitchen table, she amused her children by whirling her braids like ropes and then later sitting on them.

Although Vivian’s mother’s people were Irish, she had been raised by German adoptive parents, and she spoke with a decided German accent.

Vivian was the firstborn of the Baxter children. Her sister Leah was next, followed by brothers Tootie, Cladwell, Tommy, and Billy.

As they grew, their father made violence a part of their inheritance. He said often, “If you get in jail for theft or burglary, I will let you rot. But if you are charged with fighting, I will sell your mother to get your bail.”

The family became known as the “Bad Baxters.” If someone angered any of them, they would track the offender to his street or to his saloon. The broth- ers (armed) would enter the bar. They would station themselves at the door, at the ends of the bar, and at the toilets. Uncle Cladwell would grab a wooden chair and break it, handing Vivian a piece of the chair.

He would say, “Vivian, go kick that bastard’s ass.”

Vivian would ask, “Which one?”

Then she would take the wooden weapon and use it to beat the offender.

When her brothers said, “That’s enough,” the Baxter gang would gather their violence and quit the scene, leaving their mean reputation in the air. At home they told their fighting stories often and with great relish.

Grandmother Baxter played piano in the Baptist church and she liked to hear her children sing spiritual gospel songs. She would fill a cooler with Budweiser and stack bricks of ice cream in the refrigerator.

The same rough Baxter men led by their fierce older sister would harmonize in the kitchen on “Jesus Keep Me Near the Cross”:

There a precious fountain Free to all,

a healing stream,

Flows from Calvary’s mountain.

The Baxters were proud of their ability to sing. Uncle Tommy and Uncle Tootie had bass voices; Uncle Cladwell, Uncle Ira, and Uncle Billy were tenors; Vivian sang alto; and Aunt Leah sang a high soprano (the family said she also had a sweet trem- olo). Many years later, I heard them often, when my father, Bailey Johnson Sr., took me and my brother, called Junior, to stay with the Baxters in St. Louis. They were proud to be loud and on key. Neighbors often dropped in and joined the songfest, each trying to sing loudest.

Vivian’s father always wanted to hear about the rough games his sons played. He would listen eagerly,but if their games ended without a fight or at least a scuffle, he would blow air through his teeth and say, “That’s little boys’ play. Don’t waste my time with silly tales.”

Then he would tell Vivian, “Bibbi, these boys are too big to play little girls’ games. Don’t let them grow up to be women.”

Vivian took his instruction seriously. She promised her father she would make sure they were tough. She led her brothers to the local park and made them watch as she climbed the highest tree. She picked fights with the toughest boys in her neighborhood, never asking her brothers to help, counting on them to wade into the fight without being asked.

Her father chastised her when she called her sister a sissy.

He said, “She’s just a girl, but you are more than that. Bibbi, you are Papa’s little girl-boy. You won’t have to be so tough forever. When Cladwell gets up some size, he will take over.”

Vivian said, “If I let him.”

Everyone laughed, and recounted the escapades about when Vivian taught them how to be tough.

From the Book, MOM & ME & MOM by Maya Angelou. Copyright © 2012 by Maya Angelou. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.