Few things preserve like dense Hudson River mud. That was proven this summer when workers at the World Trade Center site uncovered the skeletal hull of an 18th century ship at the site of a future car park. Twenty-five feet below the surface, buried in grey muck in a section of Lower Manhattan that hasn’t seen light for almost two centuries, was the hull of a 32-foot merchant vessel.

On Thursday night, 40-stories above the work site, at 7 World Trade Center, the archaeologists, preservationists and a maritime historian, who teamed up to excavate the fragile pieces, explained what they’ve learned so far, and what it takes to delicately extricate some of the most fragile materials on earth.

Michael Pappalardo, the senior archaeologist with AKRF, the firm hired by the Port Authority to help document the findings, said that the boat, with its shallow hull, was most likely a merchant vessel. Little holes bored into one of the wooden posts indicate the ship spent significant time in Caribbean salt water. The holes were made by teredo worms, also known as the “termites of the sea.” The only reason they didn’t completely destroy the ship is due to the dense, oxygen-less Hudson mud, which kills all bugs.

The origin of the ship remains a mystery, but there are some clues. Pappalardo said that the irregular length of the planks, which are fit together like a puzzle, indicates the ship was built in a small, rural shipyard.

The excavators also uncovered 1,000 disparate artifacts at the site. Pappalardo rattled off a list of antique store items they found: a spoon; dozens of leather shoes; nuts; seeds; a British revolutionary war era button; various ceramic items; various animal bones; including a horse jaw (“I hate to think that was part of food, but I really don’t know,” Pappalardo says); a single coin wedged between two pieces of wood (a common superstitious symbol sailors carried); and a human hair with a preserved louse on it.

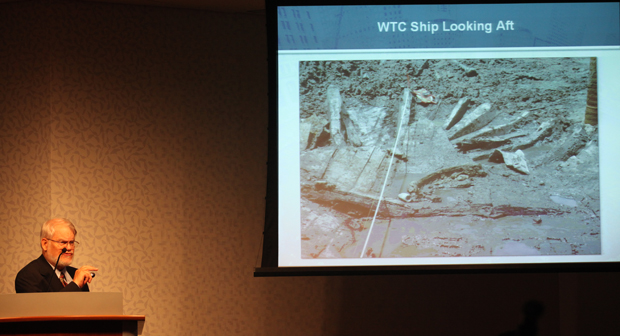

Maritime historian Norman Brouwer explaining what he's learned about the ship

During one sweltering week this July, the team of two conservators, two marine historians, three archeologists, one photographer and a few construction workers worked to unearth the ship, which they dubbed the “SS Adrian,” after the superintendant of the construction crew.

One of the archeologists, Elizabeth Meade, calls it one of the greatest projects she’s ever worked on, but says it was an exhausting week, and not terribly pleasant, tromping around in the 25-foot hole. “It has a low tide smell, it’s that river bottom, dead seaweed, old oysters kind of grossness that doesn’t leave you for awhile. It earned me the nickname Swamp Thing among my friends,” Meade says.

Nichole Daub, the head conservator at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, is in charge of preserving the ship parts. Immediately reading about the ship's discovery in The New York Times she contacted the Port Authority with a proposal offering her labs’ services. Eleven days later she was in New York on the site.

Daub said she was impressed with the round-the-clock construction at the World Trade Center site, and felt humbled to be part of the effort. Even though construction had to be ground to a halt for the ship's excavation, nobody made Daub feel like an imposition.

“It really made us realize that we were an infinitesimal ant in this large project,” Daub says. “Instead of making us feel like a wrench in the works, we were really made to feel like a cog in the machine, which was a very pleasant experience.”

After photographing every piece of the ship, taking 3D images and tagging every item found on the site, the vessel was packaged and trucked to Daub’s laboratory in Maryland for preservation. Right now, the individual pieces are floating in a saline solution for restoration purposes, but the final destination is ultimately up to the Port Authority.

It will still take four to six years to preserve some of the pieces, so the Port Authority has some time to find an appropriate home. But Daub stresses the importance of carefully protecting the 18th century artifacts.

“It would be a shame to see a ship like this deteriorate, to any degree. I will try, to the best of my abilities to ensure that doesn’t happen. But at the end of the day, the clients make the decisions,” Daub says.