The MTA’s safety campaign “If You See Something, Say Something” is a familiar message, one that urges New Yorkers to pay attention and report suspicious activity. But when a child-welfare campaign adopted a similar tone, critics told WNYC they worried about potentially harmful consequences for children and families.

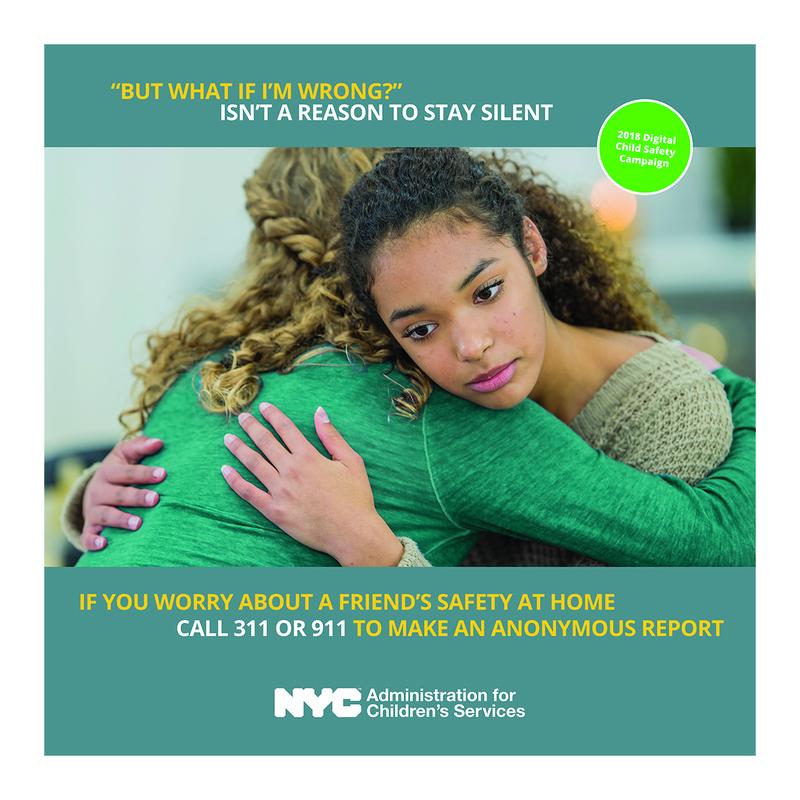

The Administration for Children's Services is running ads on Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat, in part to reach teenagers and prompt them to report their own abuse or call for a friend.

New York City launched the holiday season campaign just before Thanksgiving, touting to “double down on child safety,” according to a press release, especially during a time when schools were closed and children were out of sight of school personnel, who are mandated reporters. Reports from schools comprised 24 percent of the city’s child welfare investigations last year.

“We are dependent on New Yorkers to make sure that they're alerting us to possible situations where children may be in danger or where families need support,” said David Hansell, ACS commissioner. “So we want to make sure that all New Yorkers know how they can report concerns. And the goal of the campaign is really to provide that information.”

But children and family advocates said that families of color were particularly vulnerable because they often felt ACS spent more energy policing them than providing support.

.@ACSNYC’s new digital campaign encourages New Yorkers to say something if they see something in suspected cases of child abuse or neglect: https://t.co/K9YfqMYonv #NYCReportsAbuse pic.twitter.com/b8EIVIC7y6

— City of New York (@nycgov) November 27, 2018

It is easy to call in a report of abuse or neglect. Calls made to 311 or a hotline are directed to the State Central Register. The threshold of information needed to report is low. People can even report anonymously, which is helpful or problematic depending on how you look at it: there have been retaliatory calls from abusive spouses; even trolls have used ACS to harass others, as Shaun King, a high-profile writer on issues of racial justice, found out earlier this year.

Once the calls are recorded in the register, local agencies are required to investigate them. Last year, the city received and investigated 55,340 reports of child neglect or abuse.

It is hard to argue with an effort to keep children out of danger. But advocates questioned at least the tone of the social media campaign in that it encourages surveillance, when it very well could be offering information about support services. They said the vast majority of child-welfare investigations center on neglect, not abuse, that often stems from issues related to poverty, like inadequate housing conditions, kids not showing up to school or lack of supervision.

Of the more than 55,000 reports the city investigated in 2017, 74 percent fell into the category of neglect.

“In cases of real justified concern about serious abuse, those investigations are merited,” said Chris Gottlieb, a family defense attorney and co-director of the NYU Family Defense Clinic. “But most of the time we're talking about issues — social service issues that could be dealt with in an entirely different way.”

Gottlieb noted that even the initial ACS investigations were invasive, with front-line workers often showing up at people's homes late at night.

“It’s stressful to the parents but it's also really scary to the kids who are interviewed by strangers,” said Gottlieb. “They often don't understand what's going on. They just know something's wrong.”

After these visits, 60 percent of reports are considered unfounded.

For the cases that move forward, the city offers services or sometimes requires them. ACS workers may also seek a court order to place a child in foster care or with a relative. Overwhelming, the families entangled with ACS are black or Latino. Even the agency admits to the problem of racial disparity.

That’s partly why Joyce McMillan, a parent advocate and visiting fellow at The New School, said the social-media campaign frightened her.

“They investigate, they don't assess,” said McMillan. “So if they assessed the family, that would mean assessing their needs and then meeting them where they ought to provide the support necessary to keep the child and the family safe.”

And even though the agency has worked to remake its image, by providing more services and training, McMillan and other advocates said things have not changed for most families facing investigation.