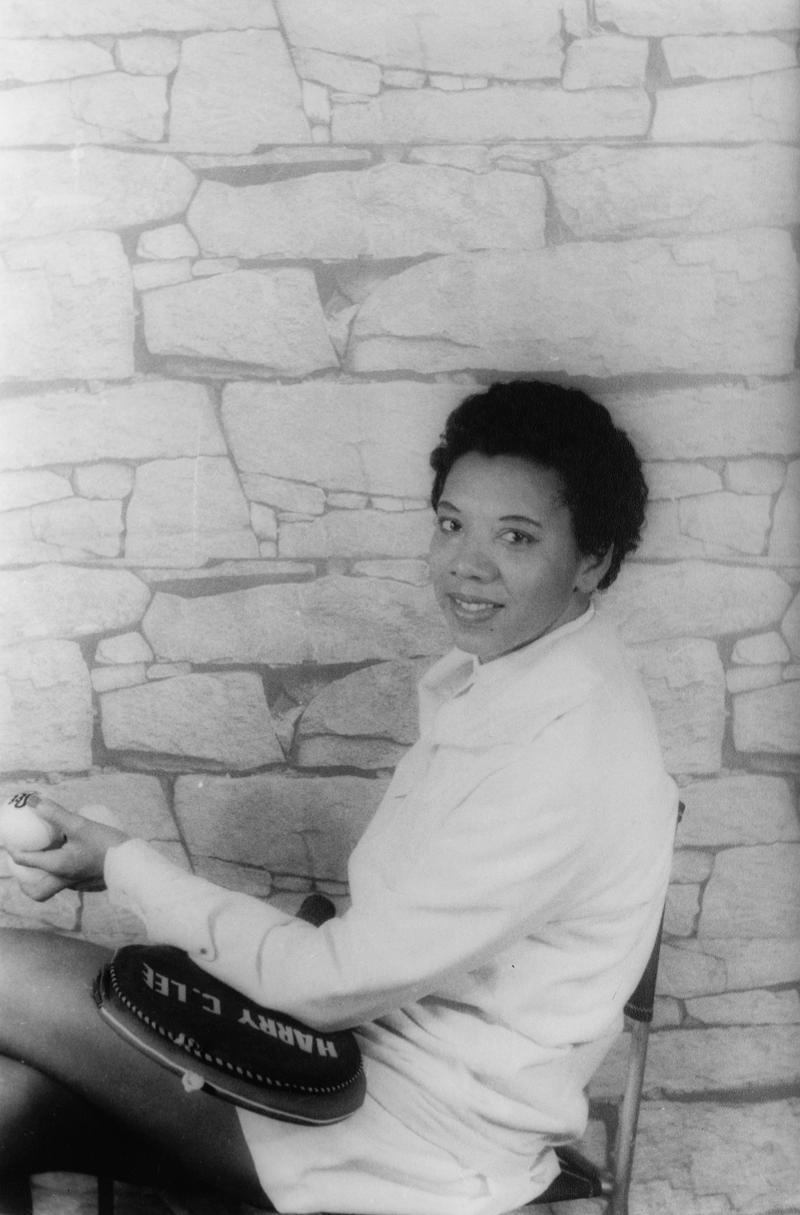

( Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress) )

Our Full Bio this month will focus on tennis great Althea Gibson, who broke barriers as one of the first Black athletes to cross the color line and compete on an international stage in tennis. She was also the first Black player to win a Grand Slam title. We're spending the week talking to Sally Jacobs, author of the biography Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson. Today, we discuss Gibson's tennis training and her college years.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in SoHo. Thank you for sharing your day with us. Coming up on the show this week, we'll speak with MSNBC host, Joy Reid, about her new book about civil rights activist Medgar Evers, and his partner in both love and action, Myrlie. Plus, a new exhibition at the Met celebrates the Harlem Renaissance. Now, this hour, we continue our Full Bio Black History Month mashup about the great Althea Gibson.

[music]

Full Bio is our book series when we take a deeply researched big biography and discuss it fully over the course of a couple of days. Our February choice dovetails with our Black History Month focus on contributions of Black New Yorkers. We'll be learning about the African-American woman who smashed the color barrier in tennis and golf, Althea Gibson. Harlem's own Althea Gibson became the first Black tennis player to win Wimbledon, the French Open, and Forest Hills, which became the US Open. She also became the first Black member of the LPGA, the Ladies Professional Golf Association.

Gibson's story is told in the book, Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson, written by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Sally Jacobs. Yesterday, we heard about Althea's tough upbringing and tougher spirit. She came to the attention of several people who hoped to nurture her talent and help her mature. She would need both to compete and to potentially make it in the Grand Slam. Althea Gibson was a bit of a wild child, a high school dropout who needed guidance on things like manners, and how to interact with other players, as well as strategically thinking about her game.

It took a village, including two well off Black doctors, Robert Johnson and Hubert Eaton, who became mentors, coaches, and eventually almost parental figures. They offered to bring her into their home to train while completing her education. Gibson completed her studies in high school and enrolled in Florida A&M University. She was much older than the other students and had a career outside of school. The issue was some in the tennis world wanted to see her play more regularly than school-allowed, and perhaps maybe integrate Forest Hills and Wimbledon.

Gibson was torn. She really liked school, and when she had a bit of a slump in competition, she considered a career in the military. It is as Jacobs writes, "A bit of a debate erupted. The issue was, what was more important, Althea's future or that of Black tennis?" Let's get into today's Full Bio about Althea Gibson.

[music]

Throughout Althea Gibson's career, you describe a series of adopted mothers and fathers sort of stand-ins. One example was Rhoda Smith. Who was Rhoda Smith and how did she help scaffold Althea Gibson?

Sally Jacobs: Rhoda Smith was a prominent ATA member in Harlem, and also a social figure, a mega member of the Cosmopolitan Club. She kind of adopted Althea at the time. Althea's parents, as you can imagine, never cottoned to tennis. They didn't know tennis. I don't think they saw her play until 1956 when she wins for First Grand Slam, 15 years after she starts playing.

Rhoda took her under her wing. She would play with her, and there were just a couple stories in the newspaper where Althea, who of course was the stronger player, even as a young person, would try to help Rhoda play better. She'd say, "Oh, I'm so sorry I hit the ball so hard. I'm so sorry." Althea, who never would apologize, was just trying so hard to help support Rhoda who helped her. Althea would stay at her house sometimes. Rhoda would go and buy her under clothes, get her a warm coat, really a step-in mom. Also, she would accompany her as Althea started to play on the ATA tournament as her chaperone in many cases.

Alison Stewart: Another big supporter, especially financially, was the boxer, Sugar Ray Robinson. How did Sugar Ray Robinson take an interest, and why did he take an interest in Althea Gibson?

Sally Jacobs: Well, they have quite a first meeting. They're both in a bowling alley. Sugar Ray love to bowl. Althea, who also love to bowl, and her girlfriends, gal pals, are bowling, and they say, "Oh, there's Sugar Ray." What does Althea do? She goes up to him and she says, "Let's play, let's do a bowling match. I think I can beat you." "Okay." He's kind of taken with that, and he comes to be very fond of her. He finds that she loves music, she plays the saxophone. She loves to sing, and it's he who puts up, I think it's $125 for her saxophone, a used saxophone, which is bought in Harlem, and she keeps with her for the rest of her life.

He and his wife, again, take her on. She travels with them. They go to one of his training sites. She's allowed to drive his car even though she doesn't have a license. It was that kind of relationship, and she always looked up to him. When she goes to Wimbledon for the first time in 1951, he's there in a boxing match, and it's he who-- when he arrives, she's there to meet him, and the press goes crazy. He just was a shining star in her life. As a young woman, I think she really looked up to both of them.

Alison Stewart: Two men who took up the cause of Althea, you call them the doctors, Dr. Hubert Eaton and Dr. Robert Johnson. Dr. Johnson became known as the godfather of Black tennis. Dr. Eaton went on to have a career as a civil rights leader. What did they see in Althea, this high school dropout?

Sally Jacobs: Well, they both had been watching her a little bit. They were regulars at every single ATA tournament, and Althea was starting to play in quite a few of them in the early '40s. Eaton actually says to one of the Black newspapers that as he would watch her, he really didn't know if she was a girl or a boy. She was so masculine looking, but he kind of moved on, he just didn't quite get it. As time went on and he realizes she's winning tournaments, he starts to pay more attention, and he realizes she's a woman, girl. They come to a tournament in 1946. The two of them are sitting in the stands. There's an ATA tournament at Wilberforce, and they're watching her.

She's not playing her best, she's playing against the great player, Roumania Peters. She's falling into her usual habit of that day, which she's getting flustered. She misses a couple shots. She gets teed off, and she rams the ball off the court out of the playing area. You don't do that in tennis, but she does. Anyway, she loses the match, but they are so impressed by how she plays, by her form, by her force that they have decided, as they're watching her, they are going to take her on as not just a student, but as a young person they're going to help get through school. She was a dropout at the time. Most ATA people did not know that because if they had, they probably wouldn't have taken her on.

They go to her that day. She's sitting in the bottom of the stairs. A lot of ATA people walk by, just so annoyed with her for losing. They barely even look at her. She's crying. Tears are going down her face. I think it's Eaton who goes up to her and he says, "I'd like to help you get to the US National Tournament." She's like, "What? Are you kidding?" Well, he means it. [chuckles] That's exactly what those two doctors do. Johnson lives in Lynchburg, Virginia. Eaton is in Wilmington, North Carolina. Eaton takes her on for-- she lives with him during the school year, then she goes to Johnson during the summers.

Eaton trains her. Each of those doctors has a tennis court in their backyard, which was beyond unusual, as you probably can imagine. They were prominent. They had a little bit of money, and this was the field of the sport that they were going to help integrate. They take her on, they take her to various tournaments, mostly during the summer in the south with Johnson. He had a beautiful car that he would drive around with four and five players in the car, and they would go from one tournament to the next. Of course, they weren't allowed to sleep in any hotels, eat in any restaurants. Life really happened in that car.

Alison Stewart: Here's Althea Gibson thanking the doctors shortly after one of her big wins at Wimbledon.

Althea Gibson: I'd like also to thank the two people who have done, I believe, the most for me in my tennis career. I'm speaking of one who's present here today, Dr. R.W. Johnson.

[applause]

It was through Dr. Johnson's unselfish contributions, which made it possible for me to travel around the USA at that particular time, to get the needed experience that I so needed to attain this victory. Dr. H.A. Eaton, who is not present here today, in whose home I receive love, encouragement, and a great deal more, while attending, or shall I say, finishing high school when, at the time, I did not care to finish. He has done a great deal for me, and for that, I thank Dr. Eaton and Dr. Johnson.

[applause]

Alison Stewart: Sally, you note Dr. Eaton realized that Althea was, as you put it, at the convergence of his two great passions, civil rights and tennis. What were his hopes for Black tennis at this time?

Sally Jacobs: Well, the color barrier had begun to shake a little bit at this point. Football had been integrated, and I think tennis was really the next sport that people, the Black community, hoped to break into. There had been a lot of talks between the ATA and the USLTA, as it was called at the time, the United States Lawn Tennis Association. Today, it's USTA, of course. They weren't really getting very far. The USLTA kept putting them off. They would come to them and say, "Look, Althea's so great. Let her play." They'd say, "Well, she's got to play in a few other tournaments. We really can't let her do that. She's got to show her stuff." The task before Eaton, Johnson, and the others was to get her wins at some of these other tournaments, more local tournaments, not the big Grand Slams, and that's exactly what they did.

Alison Stewart: You described their offer to mentor her as a bit of a leap of faith on their part initially. Why would that be the case if she were this talented?

Sally Jacobs: Well, first, because she was a woman. That was surprising to everybody, I think. Most people at the time would've thought it would've been a man that they would've taken to the gates of the USLTA, but Althea was so good at what she did. Women's tennis was coming into its own. There had been a real golden period of women's tennis the past decade. I think really the chemistry of who she was, not that she was an easy person because she wasn't altogether, but I think the chemistry was right between her and the doctors. This was the gamble they decided to take.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Sally Jacobs, the name of her book is Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson. It's our choice for Full Bio. When they began to work with her on her game, how did she respond to coaching?

Sally Jacobs: Well, Althea struggled with that, of course, because for her, it was hard to have someone tell her what to do. Eaton would write in his own book about how when she wasn't playing so well, she would get very, very quiet. Sometimes she would go inside and he worried about that, but he began to realize also that this was her determination to be great and that when she wasn't being great, when she wasn't playing well, she really got low. This was something that he had to work with and did, and he really helped her overcome some of her anxiety and some of the poor playing that she would resort to when she became anxious.

Alison Stewart: What about the coaching off the court, the manners around tennis, the way one behaves, the way one presents oneself?

Sally Jacobs: Both doctors specialized in that. Eaton had Althea at the family dinner table, of course, and would always be coaching her. His wife was a beautiful woman, very socially engaged. She would help Althea with her clothing, try to get her to dress a little better, got her to go to the prom, which was a big leap, but it was really Dr. Johnson, Dr. J, as they called him, who did the nitty gritty. He would have a whole bunch of students at his house, probably four or five, living in the house for the summer.

Every meal, they would sit around the table and he would show them how to use the right spoon, the right fork. You absolutely, you must fold, cross your legs. The men must pull out the chair for the women. Don't forget that napkin must go in your lap, [laughs] that kind of a thing. Some things that Althea had never heard of before, perhaps any of them had never heard of, but boy did they learn a lot there. One of his major lessons for them was, if the ball goes out or you think the referee has a bad call, you keep your mouth shut. You don't say, "Oh, no, no, that was in." You just keep right on going and stay quiet. That's what they did.

Alison Stewart: All that stuff around the dinner table. That's what the old folks used to call home training.

Sally Jacobs: [laughs] Exactly.

Alison Stewart: Does that child have any home training? The doctors wanted her to complete her education and enroll in college. They wanted to complete high school. That was one of the stipulations for them working with her. Why did they want her to go to college rather than get her out there on the circuit ASAP while she's young and strong?

Sally Jacobs: Well, as I mentioned, they were concerned with the whole person here. They didn't want to just have a winner to make the money, to make the ATA happy, to serve the Black community altogether. They wanted Althea to be a full person with an education so that when the day came that she couldn't play tennis, which, of course, wasn't that far off professional sports. This was amateur tennis, of course.

You get to a point where you really can't compete anymore. They wanted her to be able to get a job to make some money. You could not make any money in tennis in the amateur era. It was not until 1968, the open era, you could begin to make prize money. They really were thinking of the whole person in a way that the ATA, they wanted to pull her out of college this month, take her here that month, which became a real struggle between the two doctors and the larger leadership of the ATA

Alison Stewart: Althea Gibson goes to Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College. She was called the Gibb in college. She stuck out as compared to her peers, but not just because of her talent. What made her an unusual student at FAMC?

Sally Jacobs: Althea got special treatment in many ways. One of them is in the pool hall. Althea would go over to the men's dorm. No girl would ever do that, and she would just sashay in there, go down to the basement, and start shooting pool, at which she was very good. Not only did she shoot pool, she won pool. I found several guys who just told me the stories of their astonishment when Althea would not only show up but beat them at their own game. When she would go into the dining hall, for better or worse, she could go to the head of the line, and she often did. Some people resented it, sure.

For Althea, it also was a little bit complicated because she did have to leave campus. She often had to go play tournaments in the middle of a week, say, and that made school hard for her. It also kept her out of the loop. She would come back as one of the students was saying, and she'd say, "Okay, fill me in. What's going on? Who's doing what?" I think life wasn't totally easy for her, although she was the star there. It was a little complicated.

Alison Stewart: We're discussing the biography, Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson with author Sally Jacobs. After the break, we'll pick up with Althea Gibson's string of firsts.

[music]

This is All of It. I'm Alison Stewart in our Full Bio conversation about the book, Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson, written by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Sally Jacobs. We return to the conversation about the groundbreaking tennis star with the beginning of Gibson string of firsts and all the vitriol that came her way.

[music]

Althea Gibson begins her list of firsts. In 1949, she became the first Black woman to participate in the Indoor Eastern Championships. What issues did she face as a first?

Sally Jacobs: Well, as you can imagine, being the first Black woman, she faced a lot of racism. A lot of people would call names. Some places, she wasn't allowed to use the bathroom. Certainly couldn't use a restaurant. There's a lot of race tinged into that. I think there were some Black men who resented her coming in and becoming a first. Again, it was complicated.

Alison Stewart: When she began to compete, what was her age?

Sally Jacobs: Well, it was the style that we talked about a little bit earlier, which was that Althea was incredibly aggressive in a way that very few women were. She would rush the net almost to a fault. Her game really needed to develop a little bit. She had a lot of foot faults, which were a problem, but her success was that she was such an aggressive player. She had an incredibly strong overhand, she was daunting to play against.

Alison Stewart: In the 1940s, who were other African American tennis players in her peer group?

Sally Jacobs: One of the main people was Reginald Weir who was a doctor who was right before Althea. He had played in the indoors the year before a number of tournaments. He was a bit of an anomaly because he was allowed to play in a number of white tournaments. Not Grand Slams yet, but he was well liked. He was a doctor. The white community allowed him in, including USLTA was aware of this. He, in some ways, led the way for her. He would probably one of the main names. There were the Peter Sisters who were very talented tennis players. They were ones that Althea needed to defeat in order to move ahead, which she ultimately did. They had beaten her quite a number of times early on.

Alison Stewart: You point out that Althea Gibson had to overcome race, gender, and class. We've talked a little bit about each. I would love for you to give me-- there's so many examples in the book, just for our listeners, one example in her career at this point, in this 1940s to 1950s range where she had to deal with an issue of race, an issue of gender, and an issue of class.

Sally Jacobs: Well, the race one is easy. One of the things that happened, Althea, when she was playing with Dr. Johnson and the carload I described of folks traveling around the south. They would go to different tournaments. They would need to leave the towns they were in often by the time darkness fell because they were what were known as sundown towns. This happened once in Orangeburg, South Carolina in 1948, I believe it is. Yes. Dr. J is there with, I think it's two carloads, probably six students, six players. They have all won their tournaments, including Althea. They're over the top. They're celebrating, they're partying. They all have their trophies. So much so that they have committed a cardinal sin, which is, they have not filled up the gas tank.

Small detail. You just go fill it up. Not if you're Black and not if you're in the South, because they won't fill you up in the South because you're supposed to be gone. Dr. Johnson realizes this, and they are heading the two cars they have with all the players in them to the gas station, nervous. As one might imagine, as they pull up in the darkness, the owner comes barreling out of the front door with a gun in his hands, puts it at Althea's head. She's sitting in the passenger seat, and he says, "N word, get the hell out of here." They have no gas. What are they going to do?

They pull over to the side of the road. I think it's around 11 o'clock now, at night. They pull over and they wait thinking they're going to have to wait till sunrise to get out the gas and get out. Fortunately, some Black young people that happen to know the gas attendant. They explain the situation, the tennis, and they're allowed to get some gas and leave, but you can imagine the lesson that Dr. Johnson learned that night, which was, he would never again forget to fill up the gas tank.

Alison Stewart: When was a time when her gender really was a obstacle?

Sally Jacobs: I think gender is a complicated story because she did appear so male. I'm trying to think of a case where it was a barrier to her. It was a barrier in so many cases in any tennis tournament. I think I'm going to tell you the brief story about her gender and what it stems from, which is a complicated story, but Althea had a problem on her birth certificate. When she was born in 1927, on her birth certificate, she was born in a family home. The birth certificate that was subsequently filled out described her as a male. It gave her the name, not of Althea, but of Alger, A-L-G-E-R. It gave her father, not the name of Daniel, which he was, but he was called Duas, D-U-A-S.

These errors go unnoticed for decades until Althea, in 1954, decides to apply to the US Army, the Women's Army. I could not get the full story, but from the pieces I could get, which were several documents from the Women's Army to Althea, she apparently had a medical exam in 1954, and they were not happy with it. Now, was it a problem with her gender? Something was wrong because shortly after she has that medical exam, her father goes to the courthouse in South Carolina, in Clarendon County, and has her gender changed.

It gets changed to female. Her name is corrected. His name is corrected. Now, how did that happen? What did it mean? I don't have the final answer for that. I do know that the Women's Army was not happy with it. They write her a letter in 1955 and say, "You need to come back. You need to have some more medical tests, some more exams." I think there was a problem there. Althea decided not to go to confront it. She stopped applying. She dropped her application, end of story. I never really knew what came of that, but needless to say, gender was a complicated factor in her life. That, in itself, right there, was one of the most complicated chapters of it.

Alison Stewart: In terms of class, which is something people don't like to talk about.

Sally Jacobs: Yes. Class was an issue that hounded Althea throughout her life. Even post-tennis years, she struggled a lot. A poignant story that always haunts me about Althea. This a race thing, but it's partly class. When she wins Wimbledon, she does the ballroom, the classic ballroom dance with a white man named Lew Hoad, who was number one tennis player also, of course. She moves on, she travels away that night, but the next morning, Lew Hoad and his wife get a bag of hate mail raging at him for dancing with a Black woman, raging against Althea having a prominent position that she did.

"What are you doing dancing with that N person?" Part of this was also class. This was Wimbledon. This was the elegant society event. One of them in London society. There was just a lot of rage against her for breaking these barriers. I don't think she ever knew about all those letters, but certainly, Hoad and his wife did, and they were shocked and horrified.

Alison Stewart: On tomorrow's Full Bio, we'll discuss Althea Gibson's relationship with the press, Black and white, and recall the first time she played Wimbledon and Forest Hills, and her history making wins, and why she was a reluctant symbol of civil rights advances.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.