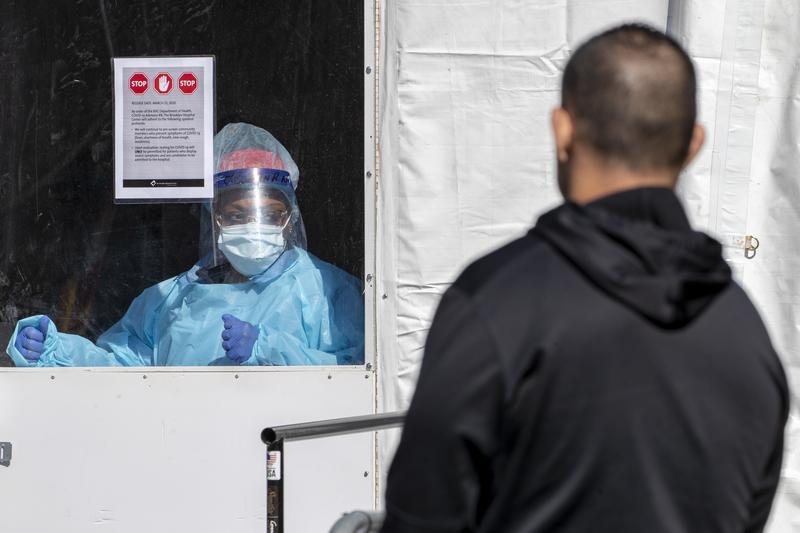

( Mary Altaffer / AP Photo )

Jay Varma, physician and epidemiologist, director, Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response, professor of Population Health Sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine talks about the latest wave of cases caused by BA.5, the possibility of an Omicron-specific booster shot this fall and more COVID news.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. We'll take a closer look now at one of the stories that Michael just reported in the news. It's the new surge in COVID cases, including severe COVID cases from the latest Omicron variant known as BA.5, and how it may seem strange that Mayor Adams is only taking steps to roll back the city's COVID infrastructure.

They just abolish the city's color-coded alert system, meaning if we enter code red territory again, which now we have according to the federal government, because of hospitalizations and other warning signs, there is not that simple method of communicating the need for caution at the city level. This week, the mayor said this about that.

Mayor Eric Adams: The color-coded system was fighting an old war, and as COVID shifted, it became a new war, so we're not going to hold on to something that's an old weapon merely because we had it, no, we're going to create new weapons to fight this new war.

Brian Lehrer: Nationally, more than 300 people every day die from COVID in the United States still, and that's been a consistent number for months now from late April. Until now, the daily average has been 300 something deaths a day, and that would be well over 100,000 more COVID deaths in a year, which is so much more than flu deaths, for example. At least we're down from the 2,500 deaths a day nationally that were recorded in January at the height of the first Omicron wave.

Vaccines and boosters and treatment medications and people having had COVID before, and the way Omicron is evolving, apparently, are all helping to keep the average severity of cases lower than before. Things are better for people who take precautions but still very serious and, again, on the cycle of more and less serious over the months getting more serious again with this increase in both cases and hospitalizations.

With me now, Dr. Jay Varma, Physician and Epidemiologist and Director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response and a Professor of Population Health Sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine. He was Mayor de Blasio Senior Advisor for Public Health during de Blasio's final year.

We'll also touch on monkeypox if we have time, but we'll also do a dedicated monkeypox segment on Monday, so, listeners, come back Monday for that. Dr. Varma, thanks for joining us today. Welcome back to WNYC.

Dr. Jay Varma: Great. Thank you, Brian, for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Should I start with a basic question maybe about this Omicron BA.5, is it different in some way from previous versions of Omicron?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. What we've really been seeing with this virus is that it keeps finding new ways to attack our defenses. What's distinct about BA.5 is it's basically following the same type of technique that the virus has used in previous iterations, but it's just gotten better at it, which is that it's modified the main protein, what we call the spike protein that's used to invade cells.

That's more of a bigger change than we've seen with any other previous versions of it. The reason that's important is that all of our immune defenses are designed against it. It's basically finding a new way to infect us that we're not as well prepared for based on either vaccines or prior infection.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, why do we keep calling these new variants Omicron, rather than go on to the next Greek letter, like when we went to Delta and then to the name Omicron last year?

Dr. Jay Varma: It's because scientists can understand how to communicate, they still want to keep being scientists. The reason I say that is because if you look at these all through the lens of a biologist, they all cluster within a similar grouping, but the reality is, you're absolutely right, we need to shift away from being scientifically precise and actually communicate in a way that actually means something.

I do wish that they would actually just shift either back to the Greek letter naming system or coming up with another way to name these so that we can communicate more effectively.

Brian Lehrer: Let me go right to the policy question at the city level. We talked in the intro about Mayor Adams abolishing the color-coded system, even though the CDC at the national level just said, "No, you're in high alert by our system for the five boroughs." Gothamist reported the other day that the city has closed about half the city-run testing sites, even though COVID testing if you're sick or frequently come in contact with people outside your own household, has always been considered a key tool for minimizing the spread. What's going on here?

Dr. Jay Varma: I have really mixed feelings about what's been going on. I absolutely understand the mayor's political imperative, which is identical to that of every other jurisdiction around the country, whether it's cities or states, which is to move the city in a way forward that doesn't appear that COVID is holding it back.

At the same time, what really troubles me is the combination of all of these factors together, not any one thing, not just the color-coded system or the testing sites, but it's really the entire package that the average person basically looks at it and says, "Okay, I don't really need to be worried about COVID anymore."

Just like with hurricane season where we're happy when we're out of that season, we don't tell people to not ever worry about weather emergencies. I wish that both the substance, as well as the messaging, continue to let people know that yes, we need to move forward, but we also need to continue our preparations, because the virus isn't done with us yet.

Brian Lehrer: This is another one of those times, just to the central point here, when everyone seems to know someone who just got COVID. Some people are asking, again, what's the good of the vaccines if so many people get COVID anyway? Is there a statistical answer to that question?

Dr. Jay Varma: There isn't, unfortunately, and I actually shy away from telling people the vaccine is X% protective against one variant or another, because the virus keeps changing, and people's immunity keeps changing.

I think the simple way to think about it is that the more defense you have, the less likely you are to suffer any of the complications of COVID. I want to make sure we all understand, the complications are not just severe illness and death that we need to worry about, their time away from work, they're transmitting it to other household members or other friends and family members who may not be protected.

Third of all, they are the long COVID symptoms that can be very debilitating in people. The more vaccine doses you get, the better you're protected, but you absolutely don't have-- there's nothing that we have that is 100% protective in any way. In some situations, it's far less than that, but I would say it's far better than nothing, especially given we know how safe these vaccines are.

Brian Lehrer: The drug companies are making Omicron-specific vaccines now, do you know the science well enough to explain what would make a vaccine Omicron-specific?

Dr. Jay Varma: I think the big issue is none of us know the right answer to which vaccine to use right now versus the next time. We know that all the vaccines are effective. The challenge we have is the Omicron-specific vaccine is targeted against an earlier version, what we call BA.1 which is the one we were worried about several months ago.

We're running into this problem where science and public policy and all the administrative levers to move a vaccine from the lab into people's arms doesn't move anywhere as fast as the virus does.

The current consensus recommendation from those of us who work in this field is that everybody who's five and above should have gotten at least three doses of the vaccine, and by vaccine, I'm really referring to pretty much any of those vaccines that are currently approved. Anybody 50 and above should have gotten four doses of vaccines, and then when the next Omicron-specific version comes out, based on everything we know, people should also be getting that as well. Also keeping in mind, however, there may be another variant, BA.6, or something else that we may be worried about by the time those all become available.

Brian Lehrer: Because skeptics say, "There's no data to show these coming vaccines are any more effective against Omicron than the vaccines we have." Some people also wonder, to your last point, if the vaccines now being tested for Omicron are really for previous sub-variants, not BA.5 or whatever may be most dominant in the fall when they would be available. Your thoughts on that?

Dr. Jay Varma: I would be concerned about that if I felt that repeated vaccination had harm. I want to emphasize what we talked about with harm. There's one sort of the obvious harm that people worry about, immediate side effects as well as long-term side effects. None of that has been shown with the hundreds of millions of people globally that have been vaccinated.

The other potential risk of harm is a little more wonky. It has to do with if I keep showing my immune system what a threat it faces, will it have difficulty recognizing that threat if the threat changes somehow? If the burglar try to get into my house, instead of wearing a mask this time, wear some other type of a hood over their head or something. That's a phenomenon that does not appear to have been seen so far. It appears that with repeated vaccinations, either these Omicron-specific ones or previous versions, you strengthen the immune response over the short term against infection, and you continue to maintain broad protection against other future versions.

Again, not 100%. All of that goes to saying that I think that these recommendations that we have to keep getting more doses of vaccine are definitely not harmful, and they are potentially helpful, which is why I recommend them to people.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take a few phone calls for Dr. Jay Varma on Omicron subvariant BA.5, and we can take a few monkeypox questions too. I will touch on it with him. He has been writing a lot about and studying a lot about monkeypox as that begins to spread now, though, as I said, we'll do a full dedicated segment on Monday. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692.

We were just talking at the individual level with the vaccines, what about at the public policy level? If Mayor Adams is removing half the testing sites that are city-funded, removing the color-coded alert system like we discussed. Also, he recently quietly ended the vaccine mandate for anybody working in person anywhere in the city, which had been in effect since late in the de Blasio administration, which you served in. What are the most important public policy measures to take now with BA.5?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine and I released a plan publicly back in early March. What's disappointing to me and others is the fact that everything we recommended then is relevant now to stop BA.5. Our tools haven't really changed. Let me just touch on those really quickly.

First of all, I would like to see high-quality masks abundantly available everywhere. It's really disappointing to me when I walk around the streets, and I still see people wearing cloth masks or-- I'm sorry. First of all, no mask at all. Second of all, cloth masks in indoor places when we know that high-quality masks can protect them. The city doesn't have to require people to wear masks, simply making them abundant everywhere in indoor facilities, which the city can do to bulk purchasing would help. That's number one.

Number two is a more proactive distribution of test kits. Not so that people have to pick them up, but they actually get delivered to people's homes. If the city doesn't feel like it can do it to every home, it could prioritize those who are the most vulnerable communities, those with the greatest barriers to healthcare access.

The third thing it can do is to change the definition of fully vaccinated to at least three doses and to actually enforce the private-sector mandate. That remains the most important mandate because we know that the risk is highest in adults, and most adults in New York are either in school or working.

The fourth thing I would say is to really amplify and actually do something about indoor air quality. The existing health code gives the Health Department the authority to regulate indoor air quality and ventilation if it wants to, and it could start promulgating standards and enforcing it in higher-risk indoor settings.

Brian Lehrer: We'll take some phone calls in a minute. Guess what? It will not surprise you our lines are full, and we'll continue with phone calls for Dr. Varma and touch on monkeypox as well as Omicron BA.5. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue to talk about the latest surge in COVID cases and the latest news as of this morning, hospitalizations beginning to rise in New York City as well enough that the Centers for Disease Control has put the five boroughs today into what it calls high alert status because of the increase in hospitalizations of COVID cases now, and they are mostly this latest Omicron subvariant called BA.5.

We're talking about this with Jay Varma, who among other things, was Mayor de Blasio's Senior Advisor for Public Health during de Blasio's last year. He's now at Weill Cornell Medicine, Physician, Epidemiologist, and more. Let's take a phone call. Here's Stephen in Brooklyn who has a specific BA.5 question. Stephen, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Stephen: Hello. How are you doing? Thank you for taking my call. I want to give you a little bit more information on the nature of this virus. What's the difference between this virus and any other viruses? This virus is more dangerous because it survives longer time on any surface than a regular virus. Flu virus survives on a doorknob for about 45 minutes. This COVID virus survives on a doorknob for about two to three days, three whole days, or a month. After anybody touches anything with the COVID virus and you sweat, somebody touches it within a month, you can get-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Let me get Dr. Varma's take on that. Surfaces, Dr. Varma, this is making me think of two years ago when COVID first started, and people were much more concerned about surfaces than they became. That seemed to be not a major source of transmission as opposed to air. What do we know?

Dr. Jay Varma: What we know is that-- I'll start with a mark of humility. It's actually very challenging to know whether somebody may have gotten infected by a contaminated surface versus the air. It's actually quite a challenging question to answer scientifically. Let's focus on what we do know.

What we do know is that this virus spreads through the air, and by the air, we mean, both over a short-range, that is people close together, but can also spread over a long-range when you're in an indoor setting. If I'm on one side of a theater, I could theoretically spread it to people on the other side of the arena if we spend enough time indoors and the ventilation is good enough.

An emphasis on indoor air quality is going to have the single biggest impact on reducing infections. Surfaces are something that we should all keep our hands clear because there are plenty of viruses that cause people to be ill, particularly stomach illnesses, but I wouldn't really be focused on that if your priority is COVID. If your priority is COVID, focus really on what's going through the air.

Brian Lehrer: Juno in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC with Dr. Varma. Hi, Juno.

Juno: Hi, Brian. Thanks so much for taking my call. I wanted to ask Dr. Varma his thoughts on my current situation. I currently have COVID for the second time, and the first time I got it was just at the end of May. At that time, I was able to take Paxlovid, which reduced my symptoms significantly so much so that I'm wondering if it impacted my immune response and thus may be more susceptible to getting it again only six weeks later, or if this is just the reality of how things are with this latest variant.

Brian Lehrer: That's pretty scary if people are getting it that close together. Have you heard this before because I think a lot of people now are assuming after they do have it that they've got an immunity pass for a few months?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. First of all, I'm sorry to hear about your situation. I hope your health gets better quickly soon. This is an excellent question. I will tell you that we don't know the absolute answer to this. What you've suggested is there's the possibility that because you took Paxlovid the first time around, that you didn't develop a robust enough immune response to protect you the second time around. That is certainly possible.

We don't know the answer to that, and I wouldn't scare people away because Paxlovid is an excellent medication at preventing hospitalizations and death, but there has been some concern in people who are vaccinated that when they take Paxlovid it may blunt your immune response. That's why some people when they take Paxlovid they get this rebound illness where they get sick a few days after getting better again, and it's believed that's because the immune system is blunted.

Now that said, because we're being hit by new variant after new variant, it is also possible that this is a new infection completely, and that you would have gotten it regardless of whether you took Paxlovid before.

What we do know is that people who are vaccinated who then get an Omicron infection tend to have better protection over some period of time than people who are unvaccinated who get Omicron, but our previous thinking that you are protected for three months up to six months, unfortunately, doesn't hold anymore because of the immune escape of these new variants.

Brian Lehrer: In terms of contagion-- and, Juno, thank you. I hope you feel better. Please call us again. In terms of contagion, can you compare this variant to the original COVID or the original Omicron because people keep saying with each new Omicron subvariant this is the most transmissible one yet, right? Originally, we used to hear you need to be in direct contact with someone who had it for like 10 minutes. Is there a number that's new and less?

Dr. Jay Varma: It's an excellent question. The reason it's scientifically hard to put a number on it is because the way in which a virus spreads through a population is a function of two major things. First of all, it's what the virus itself, its ability to infect you and spread through the air and hang around in the air, and the second is your immune response and your ability to defend against that.

Because our immune response has been changing over time, it's hard to give a number. The rule of thumb I use is that it's, to me, it's about 10 times more infectious than the original strain, these new Omicron strains, but I have a very difficult time giving a simple math number for how much more infectious BA.5 is to BA.1.

Scientists like to talk about what we call fitness which is a measure of everything together, how well it can spread through the air, how easily it infects you, how dangerous it can be once you get it, but there isn't a real strict number that I would trust anybody to give right now.

Brian Lehrer: Jenny in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC with Dr. Jay Varma. Hi, Jenny.

Jenny: Hi, good afternoon. Dr. Varma, I have a question. We've all been hearing about how vaccinated people can apparently have COVID and test negative on rapid tests, but I have a very good friend right now whose daughter had COVID, was testing positive on rapid tests. She got quite sick. Was testing negative on rapids and then she got a PCR and she tested negative. What she was told is that her immune system was "fighting the virus" but that her viral level was not high enough even to register on the PCR. This seems very confusing and potentially-

Brian Lehrer: Misleading to people.

Jenny: -dangerous.

Brian Lehrer: Dr. Varma, have you heard that kind of story before?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. I can even tell you I've heard about it in my own family when two of my kids got sick with COVID after an international trip in early June. This is a really difficult question to answer at an individual level because everybody's situation is different, and it's always possible that you had a different type of infection on top of it. Let me just go through the basics so people understand what these tests are good for and how to use them.

A PCR test is really good, not perfect, but really good at answering the question, "Do I have COVID or not?" The rapid tests are really good at answering, "Do I have enough COVID in my body that I'm potentially infectious to other people?" It's really a test of, "Do I have a high level of COVID in me?"

The third thing to keep in mind is that in people who have some type of pre-existing immunity, mostly from vaccination, but possibly from prior infection, when you first get infected with these new Omicron strains, both because of the way Omicron has a predisposition for infecting your upper respiratory tract, as well as because of your immunity, you will often, not always, but often develop symptoms first before you can detect the virus on a rapid test and possibly even before you can detect it on a PCR test because your body is basically hyper-responsive. It basically detects even the smallest amount of virus and is reacting to that.

It is very uncommon, however, for the PCR test to be negative in people who are only recently been infected and who have active symptoms but it's certainly not unheard of. What I would really recommend to people is that if you have any type of respiratory illness, you have to assume right now that it's COVID and behave accordingly.

Brian Lehrer: With the city closing PCR testing sites, in particular, as it simultaneously pushes out more at-home tests-- Home tests, obviously, offer the convenience of knowing if you're positive before heading outside, but are they interchangeable enough with PCR tests? Do PCR tests still have a significant role to play as cases and hospitalizations rise again?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. I would say the two main reasons to have PCR testing available are, number one, is for people who are presenting to an emergency department, and so they have more severe illness and you really want to be absolutely sure that they have COVID because it can impact the way you treat them and manage them. Number one, diagnosis particularly in people who have somewhat more severe illness.

Number two is, we actually need enough PCR testing because the way we detect new variants and the way we track them is by PCR testing, so, basically, you take the virus sample that you collect from somebody's body, you grow it in a lab or what we call amplify it, and once you have enough virus, then you can test its sequence.

The bigger concern that I have with testing sites being closed down-- I have two concerns. One is I wish instead of them maybe being PCR sampling sites, they were test kit distribution sites. Another place you could get rapid test kits for people who aren't severe enough to go to the hospital. Number two is I do want to make sure that there's enough PCR testing going on in the city so we can accurately keep track of new variants emerging and what the size of them is in the city.

Brian Lehrer: This also brings me to the one monkeypox question that I think we're going to have time for in this segment, which is that I see you had Washington Post and New York Times op-eds recently saying, "Failures in testing help COVID spread so much and we shouldn't make the same mistake with monkeypox." What's the relationship there?

Dr. Jay Varma: There's lots of issues to talk about monkeypox, but let's focus on the testing one. What we've learned with COVID is that anytime you have a new disease spreading through a population, your single best way to mobilize public health action is to know how that disease is spreading, and the only way you know that disease is spreading is through testing.

What's been particularly upsetting to me about the monkeypox situation is this is not like COVID. We actually have a test available here in the United States, we have vaccines that the US has already contracted for, and we even have a drug treatment that the US has contracted for, yet a response to this has been quite slow, and right now, for example, the city only has the ability to test about 10 people, 20 total tests at about 10 people per day.

The federal government has not really done a concerted effort to basically take all of those tests companies that started during COVID and have them also shift into the ability to do monkeypox. The federal government has the ability to do it if it was mobilized effectively enough at it. Our window into how much monkeypox there is is much narrower than it needs to be.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe the one additional point that it's important to make about monkeypox right now, and we just have a minute left, is that, you write in the op-ed, "Though monkeypox is being found largely among gay men in this country so far, there's no biological reason to think that's where it will concentrate." Can you just give us 30 seconds on the relevant biology?

Dr. Jay Varma: Yes. This is a virus that is primarily spread by skin-to-skin contact. Just like you know kids can get cold sores which is a herpes virus from skin-to-skin contact, this is a virus that can spread that way. It happens to be spreading among gay men because many of them have had a number of sex partners, or there's a lot of close skin-to-skin contact but there's no reason they couldn't then transmit it to other household members who could then transmit it to other people as well without any sexual contact.

Brian Lehrer: Heterosexual sex involves skin-to-skin contact too, you know?

Dr. Jay Varma: Absolutely. Of course, there's many men who have sex with both men and women as well. The reason we need to really be aggressive at monkeypox is, well, one, we need to protect those men who are getting infected now and protect other people from it, but we also need to stop it from spreading throughout the larger population. Where I do worry that particularly in daycare or child settings, there'll be quite a lot of panic if kids get diagnosed because it can look like chickenpox and parents might get appropriately concerned that, in fact, it's something else.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, more on monkeypox after the weekend. For now, we thank Dr. Jay Varma, Physician and Epidemiologist and Director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response, and a Professor of Population Health Sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine. He was Mayor de Blasio's senior advisor for Public Health during de Blasio's final year in office. Thank you so much. As always, Dr. Varma, we appreciate it a lot.

Dr. Jay Varma: Great. Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.