Bang on a Can, Sing through a Vacuum Tube

By Maggie Molloy

Mark Stewart hears the music in everyday objects. The world is his orchestra, and every pipe, tube, tabletop, and balloon is an untapped vessel just waiting to make beautiful music.

At the Bang on a Can Summer Festival at MASS MoCA each year, he invites composer and performer Fellows to do just that: create new music from the humblest of materials. He calls his daily workshop the Orchestra of Original Instruments—playfully nicknamed the “O of OI”—and anyone can be a part of it.

“The word ‘musician’ is too often used to discourage people from participating in their birthright as sound-makers,” he says. “I see it as my duty to reconnect people with that birthright.”

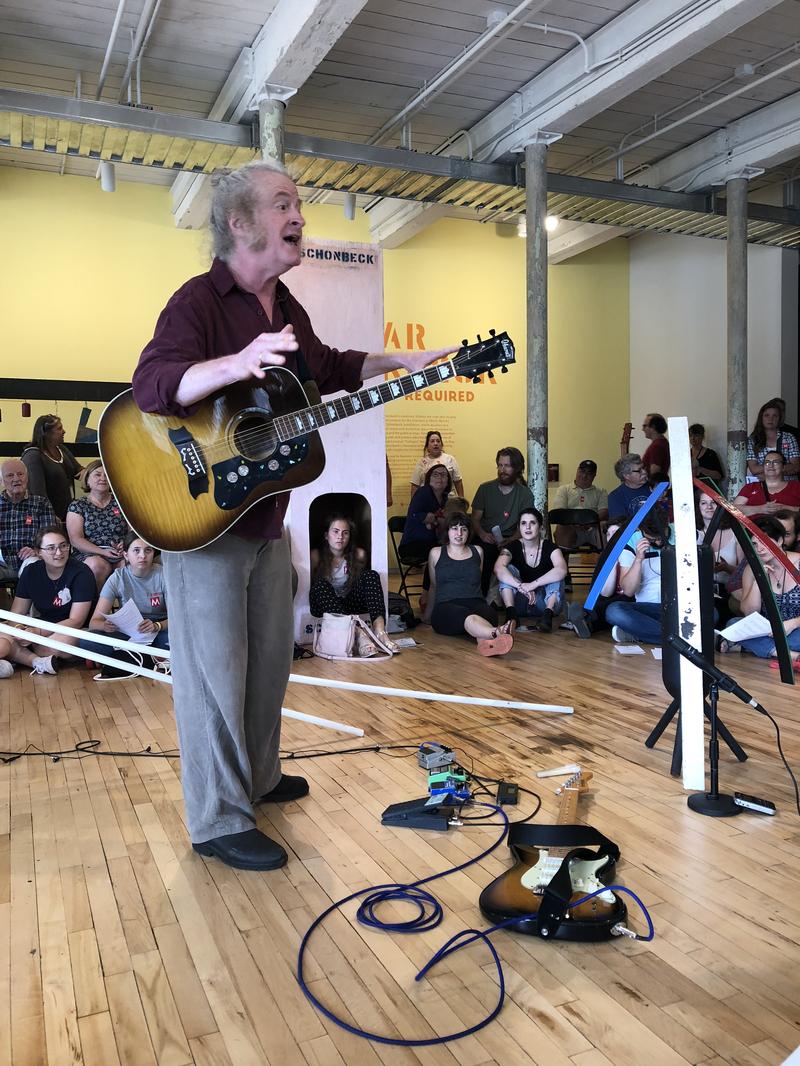

Stewart is well-versed in the art of sound-making. He’s played guitar with the Bang on a Can All-Stars since the group’s inception in 1992, and for the past two decades he’s toured the world as the guitarist and musical director for Paul Simon. He’s become a fixture of the annual Bang on a Can Summer Festival—you can spot him from across the room at any number of performances, his jovial smile framed by three-inch sideburns that blend into a waist-length mane of a ponytail.

“I spent a lot of years studying the cello, studying the guitar, trying to develop a level of mastery,” he recalls thoughtfully. “Now so much of the time I spend making sound I’m not interested in mastery, I’m interested in revelry. I’m interested in delight.”

He delighted students each day last week with his lessons in unconventional music-making. On the first day of class, dancing across the center of a circle of about 45 students, he excitedly demonstrated the vast musical possibilities of a ribbed vacuum tube: singing elephant noises through it, coiling it up into a percussion instrument, whipping it above your head like a lasso to let the overtones ring out. He calls it a Whirly, and if you connect a basic mouthpiece to it using a piece of balloon and some electrical tape, it becomes another instrument entirely: the Balloon-Powered Organ Pipe, a powerful, animalistic horn that vibrates right through your fingertips.

Later in the week, he showed students how to craft a sonic rainbow of single-reed horns by attaching saxophone mouthpieces to discarded hula hoops, plumbing pipes, wiffle ball bats, and the bones of old sousaphones. When sounded together, the result is a clamorous orchestra of big-bellied honks, bellowing howls, high-pitched squeaks, and joyous laughter.

“There are all sorts of wonderful creatures between the cracks that deserve their chance in the sun,” Stewart says. “The piano is a remarkably versatile instrument—so too is the clarinet and the violin. A cowbell, on the other hand, is an idiophone that does one thing perfectly. I like to find those other instruments that do their one thing perfectly.”

Stewart’s O of OI is the offshoot of a long lineage of unusual instruments in contemporary classical music. Perhaps the most famous is John Cage’s prepared piano, invented in 1940: an entire percussion orchestra created by placing screws, bolts, and pieces of rubber on or between the strings of a grand piano. Cage’s later works pushed the envelope even further, featuring instruments as wide-ranging as toy pianos, radios, conch shells, and even cacti. Another 20th century musical maverick, Harry Partch, took a different approach: he explored microtonality in music by crafting his own collection of idiosyncratic instruments using wood, bamboo, gongs, glass carboys, strings, and recycled organs and guitars.

Working at a more local level was the late Gunnar Schonbeck, who taught composition and ethnomusicology at Bennington College in Vermont for over five decades. During that time Schonbeck assembled a collection of hundreds of handmade instruments built from unexpected materials: 10-foot tall drums made from aircraft fuselages, two 9-foot tall banjos fashioned from concert bass drums strung with piano wire, xylophones built from 2x4s and 2x8s and 2x10s, and a whole myriad of steel pan drums, zithers, plumbing pipe chimes, and more.

Schonbeck’s instruments are now housed at MASS MoCA, where Stewart serves as curator of the collection. Stewart first discovered Schonbeck’s eclectic instrument collection at Bennington in 2011, six years after the composer’s passing. The school was no longer able to support the instrumentarium, so Stewart worked with a small team of people to relocate the surviving instruments to MASS MoCA, where they now form an exhibit titled “No Experience Required.”

“Every visitor is encouraged to play joyfully upon all these wonderful instruments, and they do,” Stewart says with excitement. “Every day that gallery is filled with people of all ages getting down.”

That spirit of openness and accessibility is critical not only to Stewart’s personal music practice but also to the broader Bang on a Can ethos. Composers Julia Wolfe, David Lang, and Michael Gordon produced the original Bang on a Can Marathon in New York in 1987 with the invitation “Come and go as you like, or stay all day.” The concerts took place in museum galleries, offered beer for sale, and skipped the program notes in favor of informally introducing pieces from the stage.

The eclectic programming was born out of a desire to celebrate new music in all its many forms, boldly placing composers from both the academic uptown and the experimental downtown music scenes on the same concert. At the time, the polarization of 20th century music between different stylistic camps had created a hostile environment for young composers, and Bang on a Can sought to erase the institutional and ideological boundaries that separated them.

“We wanted composers to feel like they were part of a community with each other, and to be cooperative and be nice and support each other,” Lang recalls. “In 1987, those were fighting words.”

Over thirty years later, Bang on a Can still embodies that sense of boundary-breaking community: last Saturday’s six-hour Marathon began with the angular melodies of Iannis Xenakis and ended with the pulsing minimalism of guest composer Steve Reich, with music of composers as wide ranging as Pamela Z, Andy Akiho, György Ligeti, and Dobrinka Tabakova woven in between.

But before the marathon even began, a crowd of around 500 people was welcomed inside the MASS MoCA performance hall by a pre-concert fanfare featuring the beautifully irreverent music of Mark Stewart and his whimsical O of OI. Though playfully less polished than the performances that followed, the fanfare brought together composers and performers alike in a powerful display of the pure joy of sound.

“I’m interested in getting simple, glorious instruments into people’s hands so that they can experience the delight of making sound,” Stewart says with an exuberant smile. “When you make sounds that are delightful, after a little while music tends to emerge.”

Maggie Molloy is a music journalist, editor, and radio host at Second Inversion. She is based in Seattle, Washington.