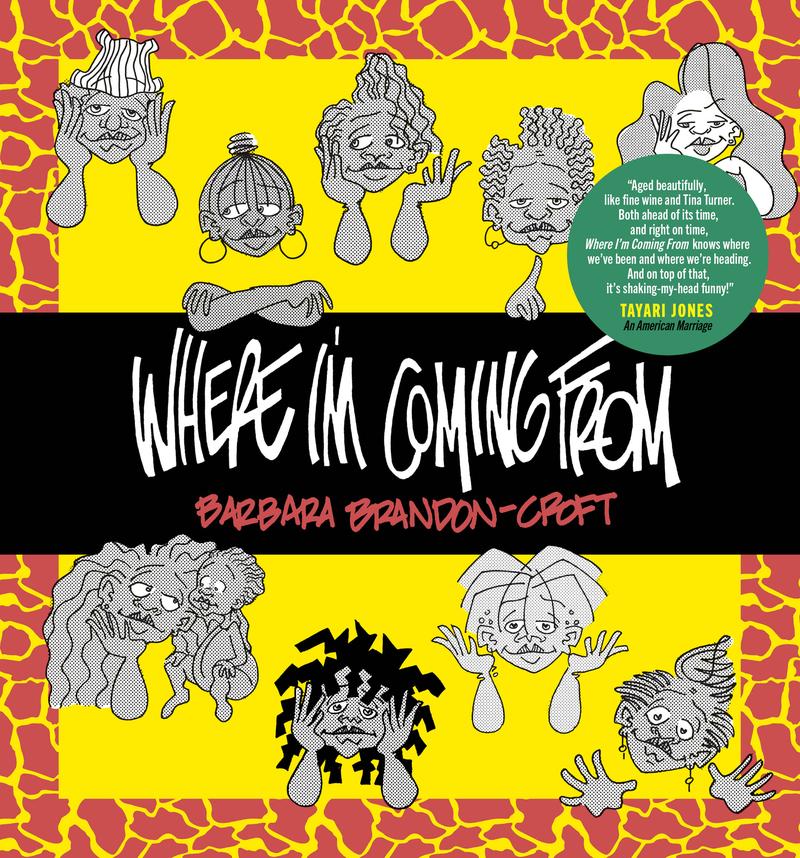

( Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. Thank you for spending part of your day with us today. Later in the week we'll talk about a revival of A Doll's House, it's now on Broadway. Jessica Chastain stars as Nora, one of theater's most demanding and iconic roles. The script has been updated by playwright Amy Herzog. They will both join me in studio that's happening on Friday. Jessica, by the way, won a SAG Award for outstanding female performance in a limited series or TV movie. Last night she looked lovely. She had a great speech, we'll talk to her about that.

We'll also speak to NPR Ari Shapiro, he and actor Alan Cumming have a new cabaret show called Och & Oy! A Considered Cabaret that will be at the Carlyle later this spring. Plus, he's written a memoir called The Best Strangers in the World. Ari Shapiro will join us to discuss both and take your calls. That is later in the week, but let's get this hour started with cartoonist Barbara Brandon-Croft.

[music]

Today in our Black Art history Series for Black History Month, we turn to the first African American woman cartoonist to have a nationally syndicated comic strip, our next guest Barbara Brandon-Croft. It all began in 1989 when Croft's trailblazing comic Where I'm Coming From became a breath of fresh air to readers of the Detroit Free Press, who saw the perspectives of Black women put at the forefront.

The strip was nationally syndicated two years later. The strip features nine reoccurring characters all of them Black women who take up space literally on the page. Some of them include voices like Lydia, the conscious single mother, like Keisha, the activist, and the outspoken woman named Monaco who's light-skinned and always batting down questions like what are you? These women discuss everything from social and justices and microaggressions to menfolk and the day-to-day events of their own lives.

A Washington Post article said, "What she delivered in her strips was a circle of friends who have an uncanny way of drawing the reader through casually conversational tones, sometimes breaking the fourth wall." Now a retrospective collection of strips titled after the pioneering illustrator includes essays and letters highlighting the cartoonist's achievement and career the book is titled Where I'm Coming From. Joining us now from Queens is Barbara Brandon-Croft. Welcome to the show.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: Why did it feel like the right time for a retrospective?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Because someone asked me if they could do it. Actually, that's how it happened. I had put it on the shelf for a while, my syndication ended in 2005, and I let it-- I was married, I had a kid, I was working. I just let it fade away until I started doing it again for myself, post-syndication. Then I got a call from Drawn and Quarterly, and they're like, "You did important work. We need to put it together a collection." I was like, "Okay, so old." I was like, "That sounds great to me." That's really how it happened.

Alison Stewart: When you started, what did you see that was missing? That you wanted to fill that void?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Well, Black women on the comic page, that was a void that was undeniable. My dad was a cartoonist, pioneer Black cartoonists had a comic strip, Luther. He came around in the late '60s early '70s, along with Morrie Turner with Wee Pals and Ted Shearer with Quincy and my dad had Luther, my dad Brumsic Brandon Jr. I guess it could be argued that at the time newspapers were looking to reflect their-- it was turbulent time was the late '60s, early '70s, and they're like, "We needed a show that we understand that we have Black readers."

It seems like it may have been more palatable to have youngsters talking. For me, when I did it I had adult women, and had them speaking and that hadn't been done before in the manner that I was doing it.

Alison Stewart: Who are some of the voices that readers have really responded to, and that you knew were going to work right away?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: You know what, I thought all of them would work right away.

Alison Stewart: You knew it.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: They were true women, I base them on myself. I base them on my friends. I base them on an honesty about what my experience is, and I just talked about everything. I got responses from women who said, "Oh, my goodness, you're killing me softly with your comic." It's like I was telling their story through my girls, I call them girls as girlfriends. I cannot say which ones stood out more. I think they all hit something in someone.

Alison Stewart: Like the Roberta Flack reference as well. Barbara Brandon-Croft is my guest. The name of the collection is Where I'm Coming From, a collection of scripts from 1989 to 2005. Before someone said yes to you, yes, Barbara, yes, let's do this comic. Why did they say no? Did they explain why they said no?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Yes. The yes that I got that was great was from Detroit Free Press. There I was published. I was like, and I knew enough about the industry because my dad was a syndicated cartoonist, that I needed a syndicate. There's no way I could get papers on my own. I'd reached out to syndicates and basically the rejections I got, and I got some nice rejections. Some thoughtful rejections, but that were-- they said, "I can't just do women, I have to include environments. I can't just do Black women. How many people are going to be interested in this outside of other Black women?" Which, of course, is insulting.

I was like, "These are just women talking and our hopes and our dreams are the same as yours, and I talk about universal themes." That's the thing I got. I didn't want to change any of that, so I didn't. I was lucky enough to get Universal Press Syndicate who said, "Okay, let's do it your way." That's how it happened?

Alison Stewart: What's a piece of advice you got from your father, either creatively, or about the nuts and bolts of this business that really proved to be useful?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: I guess I would say that one of the things that he said to me and often said to me is that, what a cartoonist's job is to do is to observe, interpret, and record, record what's happening in our lives. That's what he did in my face all my life. I saw a cartoonist's drawing. I saw what it took. I saw a real-life role model right there at my home. There's no other way that I would know that I could be a cartoonist if I had not seen him do it. It was like that immersion in that world of cartooning. I was like, "Okay, I can do this," and I did.

Alison Stewart: Were you one of those kids who was running around your dad's office while he was working and absorbing?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Yes [chuckles].

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Yes. Look, I grew up in Long Island, I grew up in Newcastle, and we lived in a small house. When my dad-- was always cartoon, but before Luther got started, and once Luther start, the beginning of it, he was working in the dining room, and the dining room was in the center of the house. At least I don't know, in my early teens, or at preteen, and I was running around and making noise, and he was like, "Calm down everybody dad is working." I was like, "Wait, he's supposed to be a cartoonist, thought this was to be a fun guy." He was very serious because he had to get his work done, so we didn't have to, but I did see it. I saw it. I saw I was down.

Alison Stewart: Your style. I think people as soon as they saw it, if they see it, if they Google it now they'll recognize right away. One of these signature things in your style, which is really effective is it's the women's faces, and their arms and their hands, but no bodies, not in a space in a place, so you really have to concentrate on their faces and their eyes and their hands. When did you come to this style for this strip? There's got to be deeper meaning to it than just like, "Oh, I just want to draw faces and hands?"

Barbara Brandon-Croft: There's a few ways to answer that. One of them is that I created it for Elan was a Black woman's magazine. I just wanted my characters to talk directly to the reader. I initially came-- and this is 1982 when I did that, and I felt that having-- and I'd stole that idea from Jules Feiffer, I'm not going to front. Jules Feiffer had a way of-- some of his comics, he would have the character talk directly to the-- and I thought that was genius, and I was like, "I'm going to borrow that."

I also was so sick of women being thought of in terms of their body parts, I am like, what's going on in their minds is what I was trying to have the focus remain on. Even everything now is music, everything is hyper-sexualized. It's like, "Well, how about what we're thinking?" I've been asked, "Are any of them fat? I was like, "Well, yes," but that's all in their mind too, if they don't think that they're the right size that's in your mind, or if you think you're really beautiful, that's also in your mind. I just wanted to focus in on their faces and what they were saying. I used the hands just to be more expressive, initially, it was just floating heads but then I started including hands and arms and gestures just for expression.

Alison Stewart: When I talk to novelists some of them will say, this character came to me very easily and another character was a little harder to nail down, of your characters who just comes to you really easily. That voice is you just grasp it and who sometimes is a little harder to corral.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: What I do is I keep notebooks on things that I want to talk about, and then I start thinking about, who could best express this, knowing my characters. The one who comes to me most easily is Lakeisha. She's the one with the dreads and she's the one when I have a point to make about social injustice, I definitely know I'm going to use her. I also use Monica who's the fair-skinned one with the light eyes and long hair because she's very socially conscious as well. Then if I want to say something that I just think is a little showing my anxiety or something, which I'm full of, I use Jackie because that's how she lives. She's always anxious about something.

Alison Stewart: Lydia comes with Riri?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Yes she does.

Alison Stewart: Tell us a little bit about Lydia and Riri.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Lydia was not a mom when I started out. Then she decided to have a baby. A choice of hers and she knew that she wasn't going to have the father involved. He explained it to her. She was cool with that. She's like, "This is something I want to do for myself" and then she wanted to name a child that demanded respect. There was Aretha Franklin her name is really Aretha and we call her Riri. That's where she came from.

Alison Stewart: We've made it sound like this just happened very easily overnight for you but you had a whole other set of careers before this all broke for you. What were some of the other jobs you had and how did they help you get to where you are?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: I went to school to study art. Had no idea what I was going to do with it. When I left-- that was Syracuse. When I left I came back and I looked in the one ads and I saw a job at Retail News Bureau. I liked fashion, they said they consider trainees. I was like, "Okay, I'm a trainee," and I took my portfolio. I was like I'm a quick learner. I like this stuff. They needed an illustrator as well, so I got that job.

When Ilan came out that was going to be a rival to essence, I was like, "Maybe I can get a job over there." I took my portfolio, I took my writing samples and said I'll do anything. Marie Brown who was the editor-in-chief at the time, she like, "You funny. You draw, can you do a comic strip?" I was like, "Yes, I can." No idea what I was going to do. A lot of things just fell into place for me, even after I ended up being a research director at Parents Magazine so I've been a fact-checker for many years. All these things fell in place and fed into what I like to do. There's no better way than to express yourself then with comics for me, there's no better way.

Alison Stewart: Why do you say there's no better way?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: You're in your home, you're on a drawing table. You're just putting out your ideas. It feels like an honor to be able to express my ideas without having to-- I don't have that immediate feedback, I'm just putting out my ideas. I can draw it up. I can send it out and then send it into the world and let it go, so to me that was ideal.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to you on a Monday after something wild happened over the weekend. We could never have known we'd be talking to you after Scott Adams who created the very popular Dilbert cartoon went on this racist anti-Black monologue over the weekend and said-- I watched it just to see it for myself. He said among other things white people need to get the hell away from Black people.

He said he moved to a neighborhood with a low Black population claiming there's a correlation between the problems in a community and the race of the people who live there. He call Black people a hate group and since then many papers have dropped in the Washington Post the Los Angeles Times, USA Today Network. Chris Quinn, the editor of the Cleveland Plain Daily said, "We will no longer carry his comic strip this is not a difficult decision". First of all, please.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: I was just going to say, this isn't his first time exposing himself of this [inaudible 00:15:05] and it's about time that the newspapers honestly it's time for the syndicate, which I think they did let him go. He is coming from a place that is full of hate and it's not even informed, it feeds into what's going on in these days at this time in life. Which honestly isn't that different than what has happened before. That's why some of the things that I talk about in my book are happening now and somebody like you could have written this yesterday because it's still happening.

The idea that this very successful cartoonist would come out of his face like that because honestly that's what he believes. He's so ill-informed and he doesn't even understand a lot. I'm glad he's off out of the papers. I hope the syndicate lets him go as well. Honestly, that's my same syndicate. That was my universal press. I think he was part of the same syndicate. I hope they let him go. There's no place for that.

Alison Stewart: Any interest in they're looking for a cartoonist would you ever consider diving back in?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: It's a whole other world now. Newspapers are dying out, and honestly, when I started in 1991 they sent out a letter saying, "Newspapers are dying. We don't know how long this is going to hold on." I don't know that I would go back to a syndicate because I don't even think it's a way to make money anymore, not that I'm making any money on Instagram but I could still-- when I have my own ideas I can just float it in Instagram or somewhere.

Alison Stewart: Just saying there are some papers with some space in your voice.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Yes. This morning. That's why I was just putting it out into the universe.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: That's how it works too. Something has to leave for you to come in.

Alison Stewart: As you reflect back as you were putting this together and you reflect back on your characters and their stories, what impact do you think you've had on people, or you hope that you've had?

Barbara Brandon-Croft: I hope that I've done exactly what my dad told me to do is really record our history and to put it down in a way that is entertaining. It's not always funny and sometimes it's heavy. I'm not trying to get people to slap their knee every time but I want them to be able to nod their head in agreement and say, "Yes, that is what we were living. That's is what our experience was." It's a nice way to contribute to the world by just recording what has happened in our lives, so years from now people can read it and say, "That's what they were going through," and maybe say, "That's what we're still going through." Which is awful but it could happen.

Alison Stewart: Or maybe learn something.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Maybe learn a thing or two. Yes.

Alison Stewart: The name of the collection is, "Where I'm Coming From," by Barbara Brandon-Croft, thank you so much for being with us, really appreciate it.

Barbara Brandon-Croft: Thank you for having me. I really appreciate it too.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.