The first batch of 1,300 New York City public high school students who got to see the hit musical "Hamilton" on Wednesday cheered like mad when creator Lin-Manuel Miranda took the stage. They whooped and hollered every time there was a kiss. And they gasped when both Hamilton and his son, Philip, died in duels.

The students weren't new to the subject matter. Their teachers used a new "Hamilton" curriculum for 11th graders known as the Hamilton Education Program, created by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in partnership with the city's Department of Education. A total of 20,000 students at high-poverty schools are using the teaching guide and seeing the show for just $10 each, thanks to an investment of almost $1.5 million by the Rockefeller Foundation.

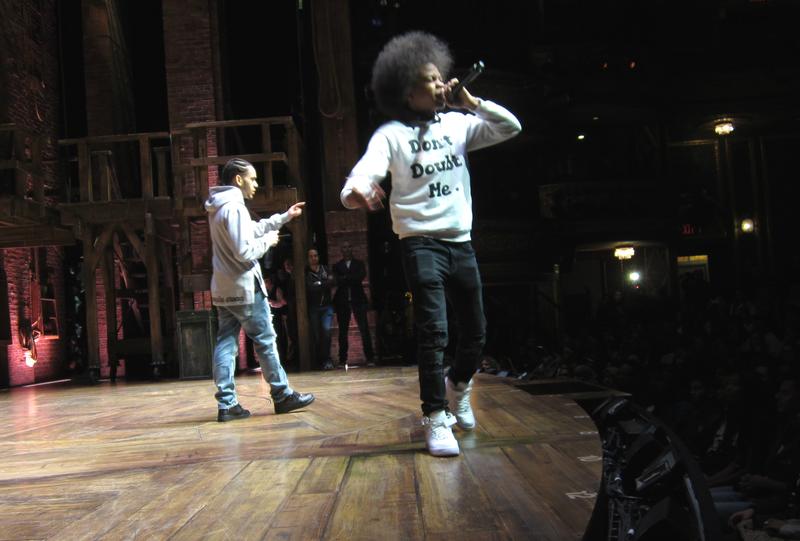

The curriculum encourages students to use some of the same primary source documents Miranda used when he wrote the show, and to write their own short pieces. Representatives from each school even performed their works on stage at the Richard Rogers Theater, for an audience of other students and "Hamilton" cast members.

I spoke with Jim Basker, president of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, before Wednesday's matinee. These are excerpts from our conversation.

Q: What was it about this show that make you think this should be a curriculum in the New York City schools?

A: It's so many things. Lin-Manuel Miranda is a genius and what he's done here is Shakespearean quality, and some have said he's the Shakespeare of America. But the quality of the language in the show, the depth of the historical understanding, the psychological acuteness of the relationships among the characters, the originality of the music, and his ability to translate both in language and in music this into the idiom of people today. It's not an elitist production at all.

Q: Students may only know Alexander Hamilton, if they know him at all, as the $10 bill. What is it about this curriculum that changes the way history is taught?

A: I think that education begins with imagination. Unless the kid feels an imaginative connection to a subject, a figure, a time they're really not going to see a purpose or any way to be engaged. So this show is supremely about imagination. About making a connection with the founding era, beginning with the story, this extraordinary story of Alexander Hamilton, the bastard orphan who becomes a huge success and is terribly important to the American founding. But then the idea of recasting the show with primarily black and Hispanic actors, that makes it accessible in a new way, reconstitutes the founding era really as something that all of us own. All people today.

Q: You're encouraging them to use primary source documents the way that Miranda did. What made you think that you could get high school students to do the same thing?

A: The focus on primary documents is, of course, essential to education across the spectrum. To literacy, to the ability to read closely and interpret language and then to paraphrase it and put it into your own language. And that's what we wanted to happen. These kids, and the exercise that's set up in their curriculum, first master these primary sources, translate them into their own language and then create their own voices using those ideas and those people.

So we've had students who discover Phillis Wheatley, the black slave teenage girl poet in Boston, who was a very important founding figure. We've had people discover that Thomas Jefferson had children by Sally Hemmings. So one of the boys at a school in the Bronx did a song in the voice of one of Thomas Jefferson's unacknowledged black children.

Q: Did you feel like you had to adapt this a little bit? It's tough enough for adults to read those primary source documents.

A: There's been no dumbing down here at all. For adults, too, founding era language is dense and difficult to access. Tim Bailey, the history teacher of the year in 2009, is our director of education. He created the curriculum where the students break it down by closely reading and paraphrasing, sentence by sentence, the documents.

Q: Have you gotten any feedback from teachers?

A: We've had some very positive initial feedback, but we are waiting for more detailed response.

Teachers have autonomy. Some of them may have used [the curriculum] for three or four days in advance. Some spread it over three weeks. The teachers know their own students best, and they know how this curriculum will fit into what they're doing in their regular school year.

The curriculum will follow the show on tour, when it opens in Chicago this September and later in California.