Bernard Baruch Looks Back…and Forward

"I'm always more interested in the present and the future than the past," the famous Wall Street millionaire, government fixer, and philanthropist admits at this 1957 Book and Author Luncheon. At eighty-seven, Baruch has published a best-selling memoir, Baruch: My Own Story, which covers his "Huck Finn" youth in South Carolina as well as his time as a speculator when he earned the nickname The Lone Wolf of Wall Street. But Baruch seems more concerned about where the United States is heading than where he has been. This talk takes place after the Soviet launch of Sputnik, which put the country at a distinct disadvantage in the space race. While US know-how was devoted to "cars and gadgets" we have neglected missiles and the Moon. He seems particularly incensed by the rise of the automobile, seeing "the path to defeat…widening to a super-highway," one we will travel in a two-tone convertible. In addition to falling behind in meaningful technology, we are also losing the battle for the hearts and minds of the world's uncommitted countries.

Baruch traces the cause to the current administration's anti-tax sentiment, which has stifled research and national preparedness. "There are worse burdens than taxes," he warns. Sputnik is "more than a satellite." It is a test of our democracy. After this ringing call to action, he rather reluctantly turns to the book he is ostensibly publicizing. But even here he dwells more on a second volume he will soon start writing, mentioning a staggering list of world leaders and captains of industry with whom he has dealt. This work will, if nothing else, "keep me out of trouble."

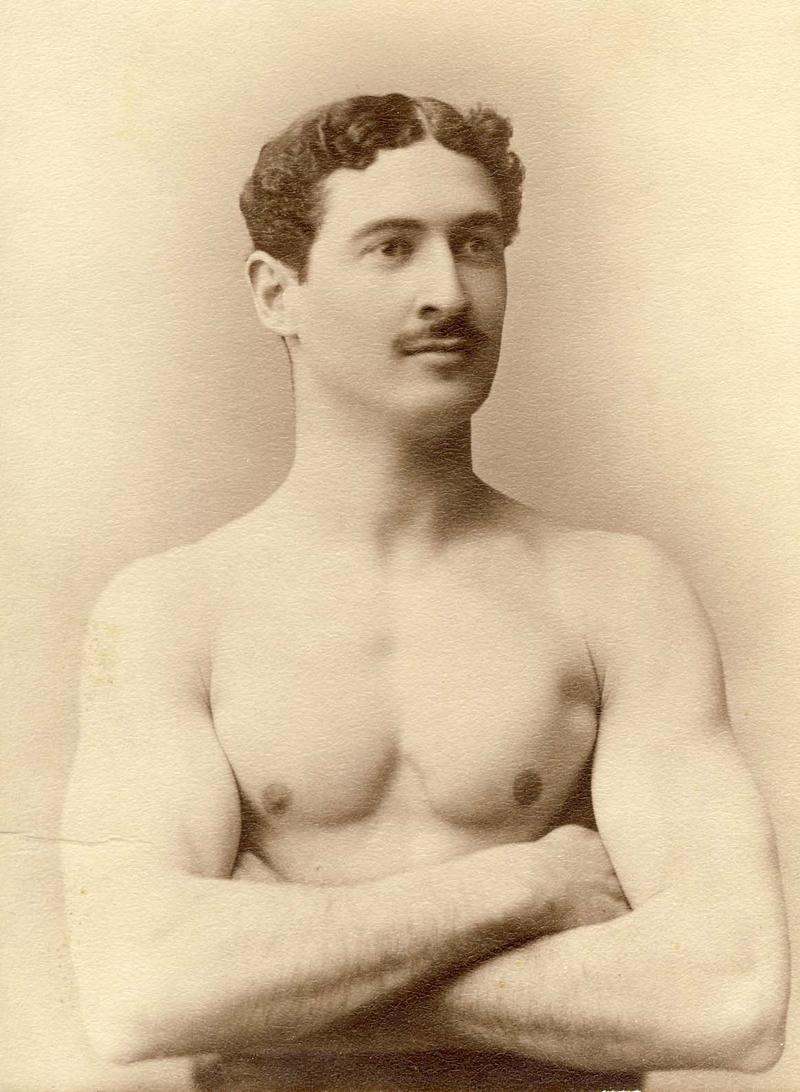

Bernard Baruch (1870-1965) cultivated the image of a simple man who conducted his business, dispensing advice and solving problems, while sitting on a park bench either in New York or Washington, DC. In fact, Baruch was an incredibly savvy financial investor and political operator who wielded enormous influence both on Wall Street and with administrations of Wilson, Roosevelt, and Truman. After buying his own seat on the Stock Exchange, Baruch amassed a fortune in the early 1900's. But his interest soon turned to public service. As the Baruch College website recounts:

When World War I began, Baruch was among the first to champion preparedness in the event of America’s entry into the war. Although his warnings went unheeded, he continued to agitate for it up until the United States’ entry in 1917, when he was appointed to the War Industries Board, eventually becoming the head of that organization. His mobilization of the resources of the country was immensely successful and he resigned at the end of 1918 to follow President Wilson to Europe for the peace conference. Baruch returned to America a changed man. While much of the country was regretting the involvement of the United States in the war and slipping back into isolationism, it was a turning point for Bernard. He decided not to return to his financial career full time and try to concentrate on public affairs as much as possible. As he himself admitted, public service was much more satisfying than making money. "At the age of forty-nine, I had already enjoyed two careers – in finance and, much more briefly, in government. The war had taken me out of Wall Street, often described as a narrow alley with a graveyard at one end and a river on the other, and plunged me deeply into the broad stream of national and international affairs."

Baruch correctly forecast the crash of '29 and, as one of the few survivors of that financial cataclysm, served as liaison between Wall Street and the new Democratic administration. The Encyclopedia Britannica tells how:

As an expert in wartime economic mobilization, Baruch was employed as an adviser by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II, although he did not hold an administrative position. After the war Baruch played an instrumental role in formulating policy at the United Nations regarding the international control of atomic energy. The designation of “elder statesman” was applied to him perhaps more often than to any other American of his time.

Yet despite having known almost every important politician from, as he says in this talk, "Reconstruction to the Age of Space," Baruch does seem to have retained some of that respect for quiet, unspectacular achievement implied by the image of the man on a bench. As the New York Times noted in its obituary:

When asked for his idea of the greatest figure of his age, Mr. Baruch responded: "The fellow that does his job every day. The mother who has children and gets up and gets the breakfast and keeps them clean and sends them of to school. The fellow who keeps the streets clean—without him we wouldn’t have any sanitation. The Unknown Soldier. Millions of men."

Thank you to Assistant Archivist Steven Calco at the Baruch College Archives for providing research assistance.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 70960

Municipal archives id: LT7743