Editor's Note: the following article was corrected to clarify the state law that established the single-test admissions rule for New York City's specialized high schools. When enacted in 1971, it applied to three high schools.

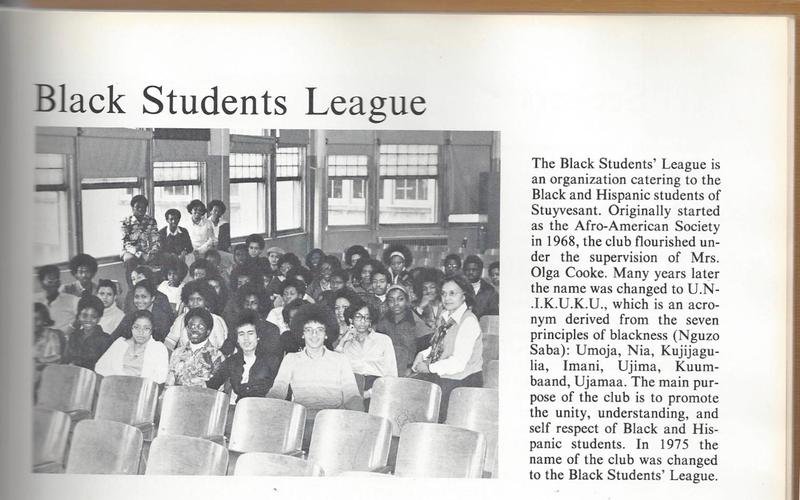

Lisa Bing was a sophomore when the number of black students at Stuyvesant High School peaked at 303 in 1975. It was a large enough cohort that they grouped themselves around interests: “Just like any other high school group there were the nerdy kids, the more social kids, the arts kids and we kind of moved in and out of all those circles.”

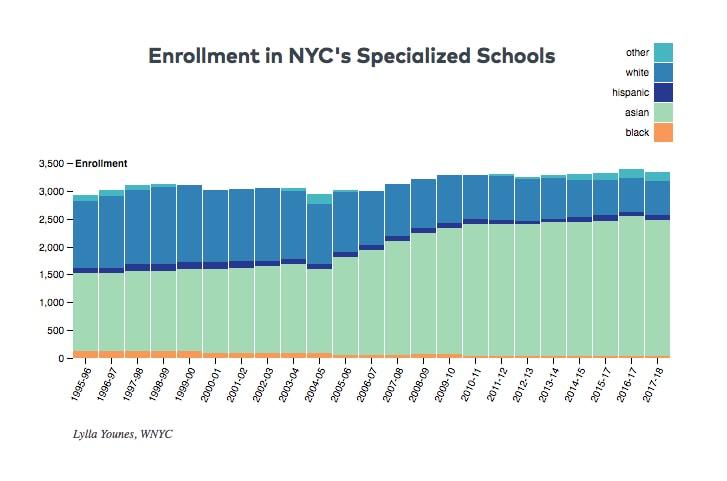

Today, less than one percent of current students at the school — one of the most competitive public schools in New York City — are black, compared to 26 percent of students across the city system. Bing said the decline in black student enrollment from the relatively high numbers she experienced was “concerning;” she saw it in the context of the many ways the city has changed since her time in high school.

The same year that black student numbers reached an all-time high at Stuyvesant, the city’s economy tanked. The 1975 financial crisis led white residents to flee the city in droves. A few years later, New York City began saw a boom in immigration from East and South Asia. The population of Asian students at Stuyvesant has steadily increased ever since, due, in part, to a focus on test-prep tutoring.

Stuyvesant’s social scene was very different when Nzingha Prescod started her freshman year in 2006 as one of just 66 black students in a student body of more than 3,000.

“It was almost like, these are the people you will be friends with,” Prescod said, reflecting on how she and other black students felt like they had to stick together in an environment where they were so outnumbered.

Prescod is a two-time Olympian and current national champion in a sport dominated by white athletes. She credited some of her success as a foil fencer to the Peter Westbrook Foundation — an organization founded by a champion black fencer to make the sport more inclusive. Prescod said the group gave her a sense of community that she didn’t readily find at Stuyvesant.

“I think when you do have that, and you feel comfortable, like ‘I can be myself, I can be like my complete like, no reservations, no hesitations, no doubts’... That’s exactly what it puts forward: a confident person,” she said. “And when you feel isolated, it diminishes your confidence.”

As specialized high schools have become increasingly less representative of city demographics, education officials have initiated recent efforts to broaden the applicant pool. Last year, they changed the test to make it more aligned with school curriculum. In 2016, the city allocated $15 million in funding to help more low-income students prepare for the standardized test that determines admission.

The single-test approach for Stuyvesant and two other specialized public high schools was enshrined into state law in 1971, and was applied to the other specialized high schools after they opened, with the exception of the performing arts school Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School which relies on a student's academic record and an audition.

Many critics have said that it should no longer serve as the sole criteria for enrollment. But some black alumni of specialized high schools are in favor of the test, including State Sen. Jamaal Bailey of the Bronx who proposed legislation that would address what he said was an issue of “access.”

Former Deputy Mayor Richard Buery is a Stuyvesant alumnus. He said the test should be one of multiple factors to make admissions more fair, but called for broader reforms to combat what he described as “an unequal distribution of opportunity” between majority black schools and others.

He told WNYC that his own experience going a middle school in East New York to Stuyvesant High School in 1984 was “a culture shock.”

Being black wasn’t the only thing that made him feel different than most other students.

“They had different preparation, different resources, different expectations that were given to them,” he said, “And I just felt that in a very guttural and physical way, pretty much every day of my high school career.”

Black students can feel pressure to defy stereotypes that they aren’t as smart as white or Asian peers — and the stress of having to prove oneself can be so intense that it can result in lower performance, according to researchers.

This “stereotype threat” can be even more intense for high-performing black students in racially diverse learning environments, said Kris Marsh, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland.

“People might think that you don’t deserve to be there, so you have to overcompensate” she said. “You [also] have to carry the burden of having to put additional networks together to carry you through the school, so beng in those isolated spaces, even though they’re one or a few of many, can be very challenging for the students.”

Bing, who went to Stuyvesant in the 70s, now consults business executives on issues related to diversity. She said a decline in black student enrollment is a loss for the whole school.

“In high school, you’re taking exams together, you’re studying together… you’re not understanding the calculus and the physics and freaking out together. Those are valuable experiences [that are] lost when you are not having intimate experiences with people who are different than you.”

Jeffreniqe Richards is a 7th grader who hopes to land a much-coveted spot at Stuyvesant. “I understand that sometimes it may be hard due to the low population of black people,” she said before she stepped into the school to meet with black alumni on a recent weeknight evening.

The 13-year-old been preparing for the specialized high school admissions test for more than a year through DREAM, one of two free city-administered test prep programs.

“I can’t wait until this summer because we’re going to use the actual book that prepares me for the test,” Richards said.

If she gets in, Richards will go from Middle School of Marketing and Legal Studies where almost 90 percent of students are black to a high school where she may well be the only black kid in most of her classes.

“I hope to represent a good stereotype for my community,” she said. “You know show that we can be, well definitely, we are smart and we can do a lot of things too.”