NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

The Brill Building's Hitmakers in Their Own Words

Before the Beatles invaded America and vocal groups dominated the pop charts, much of top 40 music was written by men sitting in an office building in Midtown Manhattan.

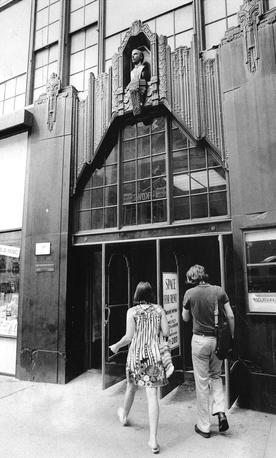

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Brill Building was a songwriting mecca, and it came to symbolize an entire industry that focused on factory-like efficiency in pop music composition. The history of the building and its neighborhood goes back to the Tin Pan Alley days of the late 19th century, when a small group of New York publishers wrote most of the popular music in the United States. Scott Joplin, Jerome Kern, and Cole Porter all wrote for Tin Pan Alley publishers. Later, Carol King, Paul Simon, and even Lou Reed did stints for music publishers, working as professional songwriters before launching their own careers.

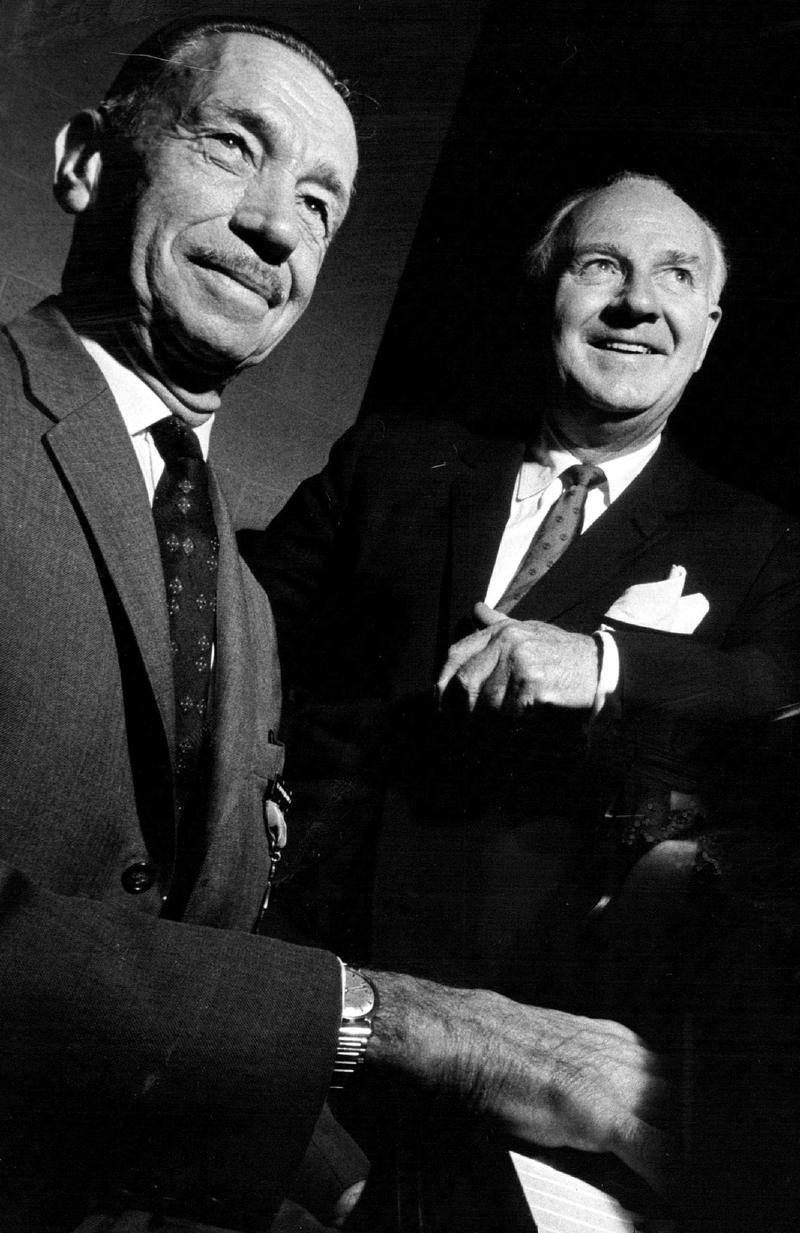

The short 1961 Banker's Trust piece above, originally meant as an ad-heavy filler for local radio, only tells part of the Brill Building's story. We also found the raw interview tapes, and those offer a more detailed picture of the state of the music industry at the time. Some of the more notable people on the raw tapes include Harry Fenster, who penned “It’s All Over But the Crying,” made famous by Hank Williams Jr.; Frank Davis, composer of “Mama Get Your Hammer, There’s a Fly on Papa’s Head.”; Harry Woods, who wrote “Try a Little Tenderness"; and Walter Bishop, who wrote songs for Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday.

Bishop tells us how in the 1930s, a good song could stay on the charts for several years. But by the time of the interview, a hit single may last only a few weeks. He blames the advent of television, people's subsequent short attention spans, and perhaps most importantly, the recent popularity of "vocal driven music".

The cult of personality surrounding pop front men in the 1960s was pushing composers and instrumental music to the background and performers to the front. The trend culminated in the oft-cited watershed moment of the Beatles appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964, only three years after these interviews. “The British Invasion and the rock revolution that followed produced some great work but also undermined the importance of the Brill Building Sound’s inspired professionalism. Instead, the replacements were hero worship and superstar egocentricity of monstrous proportions,” Steven Rosen would later write, These newly discovered interviews give us a sense of how these professional composers knew what was coming as they lament the closing chapter of that "Brill Building Sound".