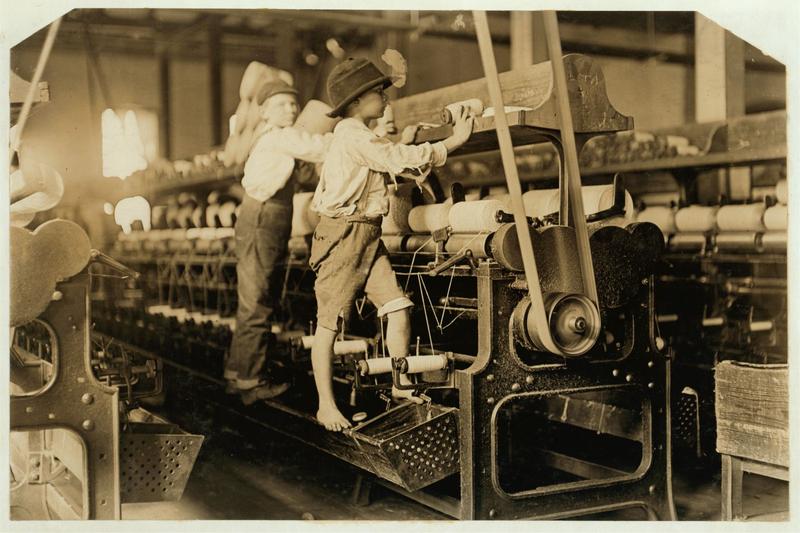

( Library of Congress) / Wikipedia Commons )

Terri Gerstein, fellow at the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School and the Economic Policy Institute, talks about the recent changes to child labor laws around the country and why a loosening of those laws may be harmful to children.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Did you hear that last month, the US Labor Department reported it had seen a 69% increase in child labor violations since 2018? In the last fiscal year alone, 835 companies, which employed over 3,800 kids, were in violation of federal labor laws. There have been reports of kids working in slaughterhouses, meatpacking plants, things you wouldn't think of minors as doing. The news comes at a time when states around the country, citing labor shortages, are actively rolling back protections for children.

In Arkansas, for example, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed the Youth Hiring Act of 2023 just last month. Under that law, children under 16 no longer have to get a permit from the division of labor there to work and the state does not have to verify the age of those under 16 for them to take a job. In Minnesota, a bill has been introduced to allow 16 and 17-year-olds to work on construction sites. In Iowa, a bill would allow 14 and 15-year-olds to work in previously-prohibited jobs like meatpacking.

Joining us now to discuss what's happening with child labor around the country and why it's happening now is Terri Gerstein, director of the State and Local Enforcement Project at the Harvard Law School's Center for Labor and a Just Economy, that's the name of the center, and a senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute. Previously, she was the labor bureau chief in the New York State Attorney General's office and a deputy commissioner in the New York State Department of Labor. Ms. Gerstein, welcome to WNYC. Thank you for joining us.

Terri Gerstein: Thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: I guess we should start with a definition. It's not illegal for a teen to have a job. What actually is the difference between an after-school or summer job, I had those when I was 15, versus what constitutes child labor?

Terri Gerstein: That's a great question and a great place to start this conversation. Of course, it's great for kids to have work and have after-school jobs and summer jobs. What it is that our laws prohibit is what's called "oppressive child labor." That falls into two broad categories. One of them is that the laws set limits in terms of the hours that children can work, that minors can work so that they're not working excessive hours or really late hours in a way that would harm their physical well-being, ability to rest, and ability to get an education.

Then the other broad category is prohibitions on the kind of work that minors can do. That basically involves prohibiting kids from being able to work or being assigned to work in really dangerous, hazardous jobs like at meatpacking plants or on construction sites or working with certain kinds of machinery. When we talk about the upsurge in child labor violations that our country is seeing, it includes violations in both of those categories.

Brian Lehrer: In your recent op-ed piece in The New York Times, which some of our listeners may have seen, you highlighted this as a recent issue in New Jersey at a Chipotle, the fast-food restaurant. Where does that come into play?

Terri Gerstein: Like a number of other fast-food restaurants, Chipotle has had significant hours violations found by enforcers in New Jersey and in Massachusetts. This involves kids working far more hours than are permitted for someone their age. Again, this may seem to people like, "Who cares if a kid works 10 minutes extra?" We're talking about kids working really, really late hours that are prohibited for a reason.

Chipotle in those two states alone paid $9 million in penalties altogether, but there have also been other similar cases. The Massachusetts AG's office, in particular, has had a real focus on this area and has brought a number of cases against fast-food employers that have violated child labor laws. They had a large-size case involving Burger King. In Washington, there was a case, I think, involving-- perhaps maybe it was Taco Bell, but this is something that is happening in a lot of fast-food restaurants, these hours violations.

Brian Lehrer: Talk about this in a local context for you as somebody who used to work for the New York State Attorney General, current laws for how many hours a minor can work in states like New York and New Jersey because we've been pretty tough, our regular listeners know, on some southern states recently, on Tennessee in our previous segment, on a number of states yesterday in terms of blocking all kinds of trans' rights and parents' rights, of trans kids. They tend to be states like Tennessee and Arkansas or out west. Idaho came up yesterday, but this is also New York and New Jersey in this case?

Terri Gerstein: Well, the governor created a task force to address child labor issues and announced that New York too had seen a rise in child labor violations. I will say that in New York, the state laws, the child labor laws are stronger than federal law. Another really important piece of this conversation relates to enforcement and enforcement resources.

Some states have almost-- we can talk about the resources at the federal level, which are grossly insufficient to the need, but then states really vary in terms of both the laws that they pass as well as the resources that they allocate to enforcing workers' rights, all kinds of workers' rights, minimum wage, overtime, as well as child labor laws. New York and New Jersey do have, relatively speaking, still insufficient enforcement resources, but more than a lot of other states around the country have.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take a few phone calls on this. If anybody has any connection to any child labor law violations, do you want to report anything, or just wants to talk about the issue or ask a question of our guest, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York, WNJT-FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are New York and New Jersey Public Radio and live streaming at wnyc.org.

In your New York Times op-ed, you wrote, "The labor market shortfall results in part from a decline in immigration and an increase in outmigration, predictable results of anti-immigrant attitudes and politics." Can you break this down for us a little bit? First, is this lacks enforcement of child labor laws, this exploitation of children that's starting to get some attention, the result of labor shortages, and to what extent are you seeing, I guess, Trump administration and to some degree continued by Biden administration immigration policies as a cause?

Terri Gerstein: Well, I think there's a lot of questions embedded in that question, right? One question is about the labor market shortage. I've certainly heard some labor experts talk about that we shouldn't even really talk about it as a labor shortage, that it's more of a good-job shortage, and that if wages were higher, if working conditions were better, that there are people who are currently not working, who might be lured back to work.

In terms of the fact that there does seem to be a real shortfall and that that's part of the stated reason that some employers and some legislators in some places are trying to loosen child labor laws, the shortfall is not at all surprising given the trends of the past five or six years. First of all, we had COVID. Our government did not sufficiently protect workers, especially in the early days of the pandemic, was not protecting workers from COVID as a serious occupational health hazard.

We have more than one million people who died of COVID. A lot of them low-wage workers, essential workers who weren't given PPE, who didn't have access to paid sick leave, and so on. Because of long COVID, there are an estimated four million people out of work. Then older Americans are also staying out of the workforce. The labor force participation rate for people over 65 has sharply declined from what you would expect it to be.

That's not really surprising, given that people are concerned about potential exposure to COVID at work and COVID has potentially greater implications for people of that age. Then in terms of immigration, both the policies and the rhetoric and all of the anti-immigrant thrust during the Trump administration did lead to a decrease in immigration and some outmigration. You look at these two factors and it sort of adds up.

I don't know the exact numbers, but it adds up to a big chunk of a labor shortage. Even so, there was a really interesting study that I saw surveying low-wage workers about meatpacking jobs, which are some of the hardest and most dangerous jobs. People said that they would go back to work and would take those jobs if they paid just a little better and that the dollar amount was if they paid $2.85 more per hour, that that was the threshold at which people were like, "Yes, I would take that job."

We look at our minimum wage. Our federal minimum wage has not been increased in over 13 years. It's a situation where if you want people to make the decision, say those people who are over 65, who might be potentially lured back to the workplace, you have to give them safe working conditions, good pay, better working conditions in order to attract workers.

Brian Lehrer: It's kind of not just supply and demand when we talk about capitalism in this respect. It's supply and demand and vulnerability. The issue is also that unaccompanied minors are the immigrants that are allowed into this country more than other immigrants. The New York Times stories on this, which really elevated the issue, reported, for example, the number of unaccompanied minors entering the United States climbed to a high of 130,000 last year, three times what it was five years earlier, and this summer is expected to bring another wave. Supply and demand meets vulnerability?

Terri Gerstein: Yes, I think that's a very good way of encapsulating this. Also, we do have these states that are looking to loosen child labor laws, not just applicable to unaccompanied minors, or these extremely vulnerable kids, but for everyone. I think the unaccompanied minors are particularly vulnerable. There are certainly seems to be need for reexamining their placement process by the federal government and more vetting of sponsors and more follow-up related to unaccompanied minors.

Certainly making sure one clear need is if they have work permits, that would enable them to get the above-board, age-appropriate, law-abiding employer jobs that would enable them to earn money that they and their families need and, at the same time, not in a way that's so harmful. It is interesting because this weakening of laws, the law in Arkansas, that eliminates the need for employers to get a work permit from the state government for children to get working papers.

That requirement required kids to show proof of age and show parental consent, as well as describing the work that they would be doing. Now, that requirement doesn't exist anymore. These weakening of laws allowing kids to do a broader range of work, which is being proposed in some states, or just more readily be employed as happened in Arkansas, that really opens the door to a very wide range of vulnerable kids being in situations that are not really ideal or appropriate for them.

Brian Lehrer: As we run out of time, I'll refer people to your New York Times op-ed for a number of proposed solutions. I just want to point out one other thing from that and have you give us a quick thought. Actually, from The New York Times reporting on this story, not from your op-ed, that the Labor Department tracks the deaths of foreign-born child workers but no longer makes them public. What?

Terri Gerstein: I think transparency is a really important part of this, but in the end, I think we really need more funding for labor enforcement. The US Department of Labor's Wage and Hour Division, it enforces not just the child labor laws but also minimum wage and overtime and a number of other laws. In 1948, they had 1,000 investigators. Last year, they had 725 investigators. Meanwhile, the workforce is nearly eight times as big.

OSHA, which enforces workplace safety and health, in 2020, and this number changes a little from year to year, it would have taken OSHA 165 years to inspect every workplace under its jurisdiction. Our funding is grossly insufficient. The other major proposal that I think is so important is to create some kind of liability for these lead corporations that are at the top of supply chains because what they do often is they use staffing companies and subcontractors to do the direct hiring.

That's a way for the name-brand, household name companies to avoid responsibility for these violations. We all read in The New York Times article and reporting that, for example, there were kids working on packaging Cheerios. Those kids weren't directly employed by General Mills, the company that makes Cheerios. They were employed by a subcontractor and hired by a staffing company. These kinds of models of using subcontractors and staffing companies really allow the top-level companies to avoid liability. That's something that needs to change.

Brian Lehrer: Terri Gerstein, director of the State and Local Enforcement Project at the Harvard Law School's Center for Labor and a Just Economy and a senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute think tank. Thanks so much for coming on and describing this.

Terri Gerstein: Thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to share these thoughts.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.