NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Christie R. Bohnsack: WNYC's First Director

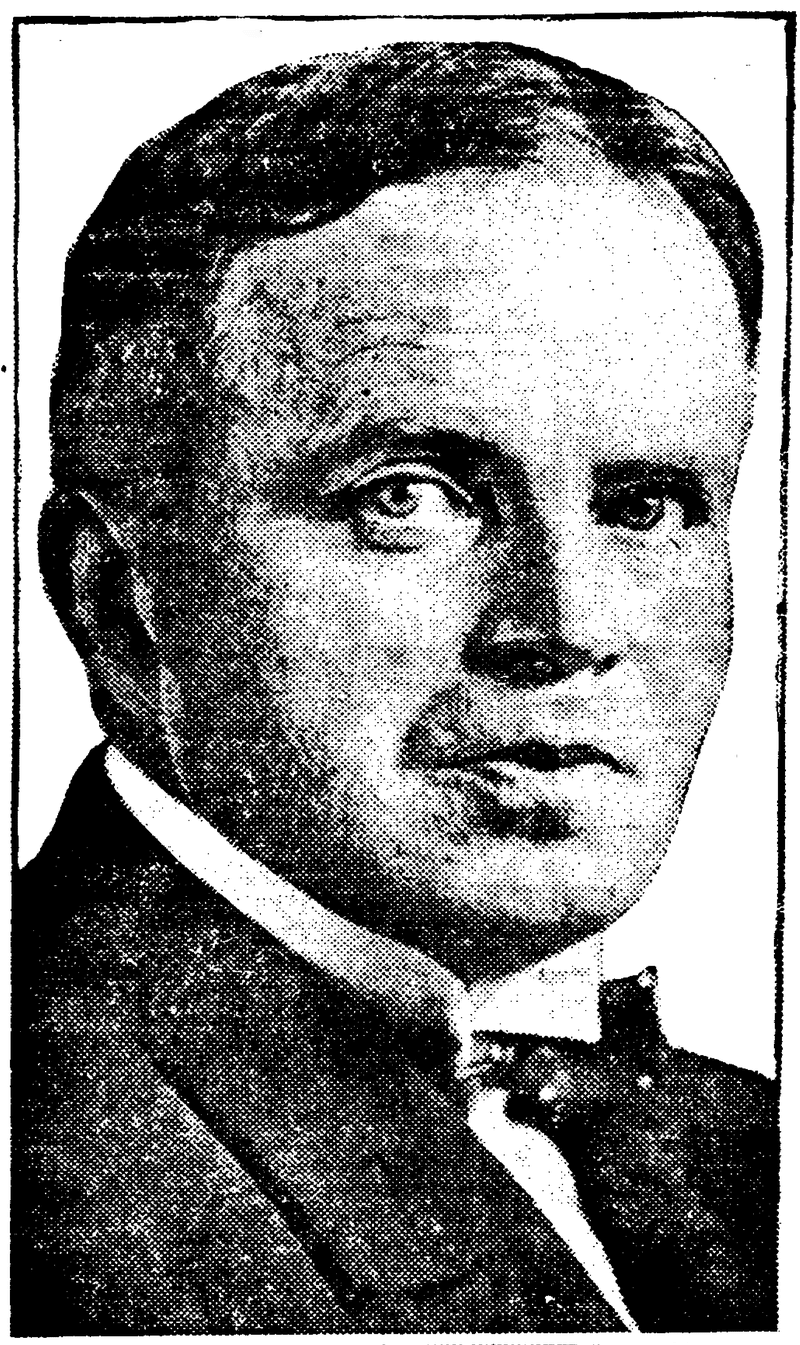

Christie R. Bohnsack (1882-1964) oversaw the day-to-day running and programming of WNYC for its first fourteen years. He was a creature of the reigning political power at City Hall and Tammany Hall who was given a meager staff and budget, in contrast to the station's mission and competition on an emerging media platform. It was a challenge, that despite being handicapped from the start, was met with resourcefulness and blindspots.

Before WNYC

Bohnsack had been the City Hall reporter for the New York City News Association, an early non-profit pool of member newspapers organized to gather, share, and distribute news. A regular at City Hall events and receptions sponsored by the Mayor's Committee on Reception for Distinguished Guests, he had become known as "the mayor of Park Row," New York City's version of London's Fleet Street. At these events, he befriended Grover Whalen, Mayor Hylan's Commissioner for Bridges, Plant, and Structures and Vice Chair of the Mayor's Committee. This connection led Whalen, WNYC's founder, to hire Bohnsack as the station's first director at $4,000 a year when WNYC went on the air in July 1924.

Bohnsack has almost grown up with Commissioner Whalen. Together they've weathered many a fancy welcoming party, and while Mr. Whalen escorted the guests of honor to the steps of the City Hall, Bohnsack was chaperoning camera men and making things easier for the gentlemen of the press...Bohnsack marshaled the taxicabs, sent notices to all the newspapers where to meet him, and escorted the boys to the scene of action.[1]

A producer, a fixer, and advance man, Bohnsack was described as "dapper and well-dressed" and frequently wore a boutonniere.

His hair is gray, his step is lithe. His chin juts out above a piccadilly collar whose points almost always extend just above the neat knot of a polka-dot blue bow tie.[2]

Putting a newspaperman in charge of a radio station may not have been ideal. But radio was still very much in its infancy, and everyone in the field was a newcomer, so a man like Bohnsack, a journalist, well-versed in public relations and logistics, may not have been too far from what was needed. To his great disadvantage, however, there was no actual budget for programming while WEAF, WOR, WHN, and other competitors in New York City radio were far better fixed. Still, in WNYC's first year, Bohnsack had somehow managed to arrange a series of regularly scheduled high-profile performers via remote hotel pick-ups with popular dance and concert bands. These included the Ben Bernie Orchestra, the Hugo Reisenfeld Orchestra, Enrique Madriguera, Vincent Lopez, and Ace Brigode and His Virginians. There was even a live Sunday feed from Brooklyn's Mark Strand Theatre that included "the first actual radio studio settings that have been presented on the stage of any theater."[3]

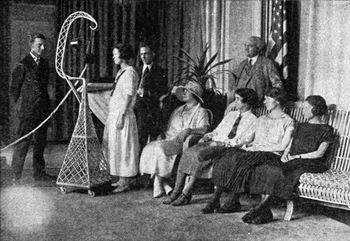

In the summer of 1925, when the city launched its first free municipal outdoor opera series, WNYC carried Verdi's Aida live from Ebbets Field with a cast of more than 400 policemen playing Egyptian soldiers, and camels and elephants borrowed from the Bronx Zoo.[4] There was also a series of special location-themed variety nights from the station's rooftop facility, outfitted with potted palms and floral arrangements. "This outdoor studio has proved to be a great boon on hot nights," said Bohnsack. "We recently staged a State of Mississippi Night...Our microphone is simply extended outside, and the soloist or ensemble [is] picked up and carried to our transmitter."[5] Another 'Summer of '25' broadcast showcase from the rooftop studio was the 'Charming Girl Contest' that included a 'phantom trip to Asbury Park, the playground of the East.' Some 300 young women were invited to the Big Apple as guests of The New York Daily Mirror and New York City. Bohnsack's task as emcee was outlined by the Asbury Park Press:

Mr. Bohnsack will give a mental picture of the triumphant parade of the girls down Broadway to the Battery, where they will board a floating palace and start on the pleasure cruise... He will tell how they are going up the gangway. Then his talk will be broken by the cheers of as many girls who can crowd in the broadcasting studio, the shrill whistles of steamboats and harbor tugs, the firing of salutes from the harbor forts and the 1,001 other noises with which New York will send 300 of her most charming girls away.[6]

This was to be followed by the Original Charlestown Orchestra with some 'sobbing saxophones' and 'the scraping of feet of the happy girl dancers' and Asbury Park's Mayor explaining why his town has become the 'Deauville of America.' " Newspaper columnist Edward T. O'Loughlin recalled these broadcasts with Bohnsack and chief announcer Tommy Cowan.

Bohnsack, Cowan and I put on a series of programs that pleased Whalen immensely, and the succession of "nights" we broadcast became very popular. Our readers may recall "Brooklyn Night," "Flatbush Night," "Greenpoint Night" "Harlem Night," "Coney Island Night" (when we introduced Sam Gumpertz's Wild Man of Borneo) and a hundred other features that won the public back to WNYC and, as it were, took Mayor Hylan "off the hook" of popular discontent. [7]

Mayor Hylan had come under attack for his partisan abuse of the airwaves, prompting a Citizens Union suit to shut down the station. While not bounced from the air, the court ordered WNYC could not be used for "broadcasting any political speeches or propaganda...for the political advantage of any official of the City of New York." Bohnsack and his staff had to counter the bad publicity. One approach was to fall back on his friends at the New York Evening Journal for a piece solicitous of public programming ideas where he could underscore the station's mission.

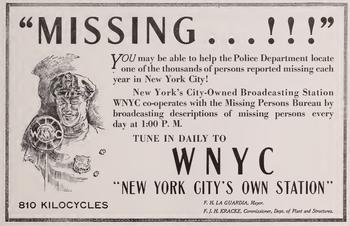

The programmes of WNYC are planned to aid in the administrating of our laws and in helping people to learn more about the great city. We are rather unique. Few cities take an active part in broadcasting but we consider it well worthwhile. Public benefits such as free operas and band concerts, are more widely enjoyed through the medium of broadcasting and missing persons are more easily found when they are described by radio. We are always ready to help in an emergency, and special messages of interest to the people are frequently broadcast.[8]

The police department's missing person reports were a daily feature and part of a significant communications relationship between the station and the police in the mid-1920s involving signaling equipment developed by AT&T. This NYPD connection was reinforced when Bohnsack took a year-and-a-half leave from WNYC to be newly appointed Police Commissioner Grover Whalen's chief spokesperson and press liaison at the end of 1928. He told the New York Evening Post then, "All I'm here for is to take a lot of routine out of Grover's hands. When any of the newspaper boys want something, I'll give it to them. If there's any wild rumors around -- understand, we're not dealing in rumors anymore-- but if any do crop up, I'll run 'em down."[9] John Fitzpatrick, Bohnsack's assistant, was made acting director of WNYC.

Still, Bohnsack and his tiny staff had to work hard to produce programming on the cheap. One strategy was to take advantage of New York, a city of dreams, where the streets were full of aspiring performers. On November 16, 1928, Bohnsack testified before the Federal Radio Commission in WNYC's battle with WMCA over the 570 kc frequency.

As to the character of our musical artists, we give auditions every Saturday afternoon from two to five. We give them during the week to persons who are not able to appear on Saturday. Our aim is to aid every person who feels that he or she has some latent ability, to appear on the radio. We do not restrict our programs to the very high type of artists, because we are unable to pay them, as commercial stations are. That of course is quite a handicap as you will realize. [10]

Later, the amateur focus would be limited to civil service employees whose talent hour Bohnsack launched in May 1935. Eighteen amateurs stepped before the microphone to perform their specialties for listeners. Among them: William Schauffbauer, a street cleaner from Queens who sang Little Mother of Mine; Eighth Avenue subway conductor Harry Griffo; a tenor from the Bronx who performed It is Not True in Italian; and Lawrence Miller, a laborer at the Department of Highways from the Bronx, a one-man band. He simultaneously played a guitar, bass drum, harmonica, and kazoo.

From the get-go, Bohnsack saw to drawing on the free stable of city officials and agency heads from the Department of Markets and Health, the Municipal Reference Library's Rebecca Rankin, and a regular flow of doctors and dentists connected to area professional associations to highlight their expertise, triumphs, and services. A handful of veterans and civic groups including the NAACP garnered weekly time slots. There were also shorthand contests, regular Spanish, French, and German lessons from V. H. Berlitz, radio's first quiz show, sports talks by Thornton Fisher, health talks from Olympian Joe Ruddy, literary criticism from W. O. Tewson, fringe lectures by the explorer James Churchward, talks on the fundamentals of aviation, countless entertainers like the Flanagan Brothers, and Locust Sisters, and frequent monologues on language from the "dean of lexicographers," Funk and Wagnalls' F. H. Vizetelly. WNYC, too, had the advantage of having a ringside seat for the steady stream of receptions and dinners of visiting royalty, aviation pioneers, explorers, athletes, and statesmen who arrived with great fanfare at City Hall.

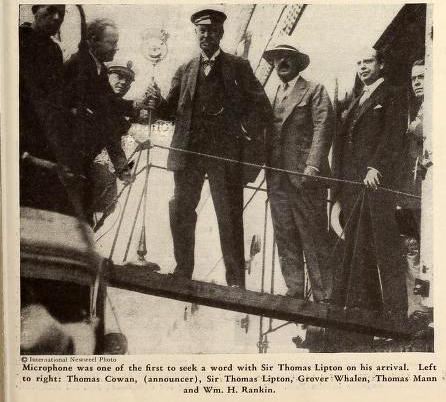

As a Mayor's reception committee member, Bohnsack orchestrated these events and set up a pool feed for other broadcasters, with Tommy Cowan as the lead announcer. One newspaper columnist wrote that Bohnsack was necessary for the success of these affairs because he "so efficiently takes care of publicity, the newspapermen and radio announcers. He is always a smiling, unruffled person, even in his busiest moments -- and to my mind -- one of the most popular men in New York."[11] Edward T. O'Loughlin recalled:

His was a delicate task and he took great care that there should be no slip up. I worked with him on many of these occasions and was a spectator of the diplomacy he exercised in carrying out his job. But there were times where we had to act quickly and take on our shoulders responsibility that required instant decision.[12]

The choreography for these star-studded receptions often began by meeting the man or woman of the hour as they sailed into New York harbor. Then, transferring them to the Macom, the mayoral reception committee "yacht," the celebrity would be escorted personally by Grover Whalen to South Ferry and then City Hall. For some notables there was a ticker-tape parade up Broadway in between, with thousands of New Yorkers cheering from the sidelines.

The Macom had been specially outfitted with WNYC gear so that Cowan could broadcast "word pictures" of the celebrity arrival and boarding as it unfolded. The renowned included: Charles Lindbergh, English Channel swimmer Gertrude Ederle; Queen Marie of Romania; Guglielmo Marconi; Albert Einstein; Amelia Earhart; Commander Richard E. Byrd; golfer Bobby Jones; Prince Gustavus Adolphus and Princess Louise of Sweden; yachtsman Thomas Lipton; and aviator Wiley Post.

In March 1927, Bohnsack joined with CCNY Acting President Dr. Frederick B. Robinson to launch WNYC's Air College, a new school of radio talks, "each lecture will be complete in itself, though in certain fields there are groups of related courses...The foreign language department will take up great French and German authors, and German folksongs will be sung and explained. Science will not be omitted, and outstanding principles of biology, physics, and chemistry will be presented in popular form. Furthermore, practical hints on public address and argumentation will be given by the public speaking department."[13]

The Air College was joined in 1929 by an experiment with the New York City Board of Education: early multimedia programming that involved providing the schools with lantern slides synchronized with a WNYC broadcast lecture series given by participating museum experts. The speakers hailed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Historical Society, the Roerich Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Brooklyn Museum.[14] The station's "educational" programming roster also boasted a Hunter College music appreciation course underwritten by Adolph Lewisohn. In addition, 1929 saw the launch of The Masterwork Hour, radio's first regularly scheduled broadcast of commercially recorded classical music and Around the Disc, radio's first record review program.

Shortly after launching the Air College lectures, political wrangling and calls for frequency reform by the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), the agency demanded that WNYC share its desirable 570 kc frequency ("first on the dial") with WMCA and WGCP. Bohnsack told Radio World magazine: "We are not looking for a fight. We fully realize the problems which the control board faces. However, the City of New York is big enough to run full-time on an exclusive wavelength. If not, we'll shut down. Why should the city divide time with a commercial station? We want to help the commission in every way possible, but in doing so, we do not want any entanglements."[15] Bohnsack and others went to Washington to plead WNYC's case.

In the meantime, as radio programming and techniques progressed, Bohnsack needed help to compete with the networks. Lectures, amateurs, those seeking exposure and coverage of city-sponsored events, and freebie performers were only enough to fill some of the time. WNYC often had to fall back on solo piano performances by music director Herman Neuman to fill airtime. This lack of novelty and innovation led to harsh criticism, the frequency-sharing Bohnsack tried to avoid, and WNYC's ultimate forfeiture in April 1932 of the 570 k.c. frequency to WMCA in exchange for the inferior 810 k.c. requiring a sundown sign-off.

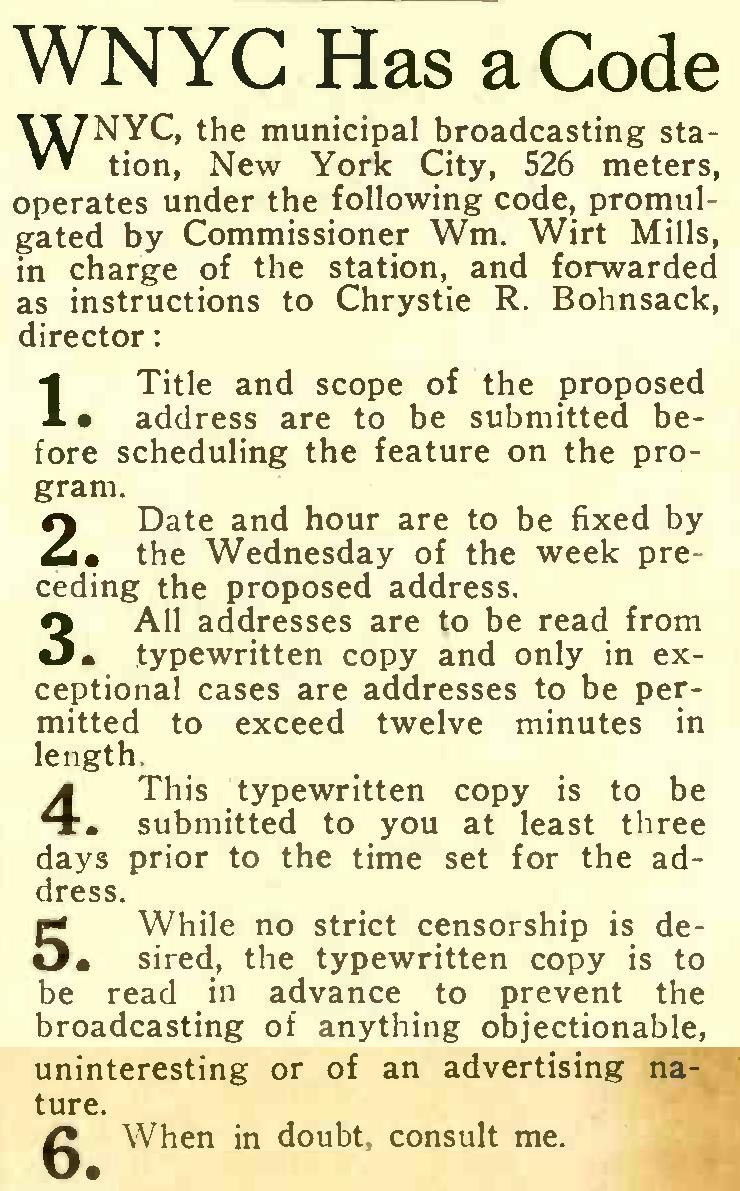

Control of the Air and Censorship

Mayor Hylan's partisan abuse of WNYC was undoubtedly an early lesson to Bohnsack to be as even-handed and on guard about what could and could not be broadcast. He was, perhaps, overly cautious. Programming was also twice as vulnerable to critique since WNYC was funded by the taxpayer and licensed by the government. Initially, studio talks followed these rules:

There was one particularly notable remote event where Bohnsack pulled the plug on a speaker that drew fire for censorship: Maine Congressman Carroll L. Beedy whose December 15, 1927 dinner speech attacking the press for its lurid coverage of a murder trial was too much for the former newspaperman. Time magazine reported:

Banqueters looked at each other with amazement and terror. “Beedy is rash and foolish,” said several. Others cried: “Beedy is right!” All agreed that his remarks, as transmitted through many a radio set into many a cozy sitting room, would rouse wide comment of approval or annoyance. Next morning they asked their friends who had been “listening in” what reaction Mr. Beedy’s words had aroused. “What did he talk about?” said the friends. Banqueters soon learned that, considering his remarks too controversial for radio consumption, Christopher Bohnsack, director of WNYC, Manhattan municipal radio station, had turned a switch which had effectively prevented Mr. Beedy’s controversial words from going through the air.[16]

This wasn't the first time Bohnsack censored a talk. A year-and-a-half earlier WNYC joined WEAF, WJZ, and WMCA in denying Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas an opportunity to criticize military training in the public schools, calling his position "controversial." Writing in the party's newspaper, Thomas said he had proposed either a talk or a debate.

I explained what I wanted. Now while I reach in my pocket for the answer, think over the speeches you have heard on WNYC. Did any of them glorify one official or express one point of view as against others? You know the answer. Now let me read: reply to your letter of May 10, "I must rule that the matter referred to is of a controversial nature and therefore inadmissible for broadcasting from WNYC."[17]

In 1946 Variety's radio editor Robert J. Landry described the station's early handling of hot topics as being excessively timid and more likely to censor than most commercial stations,[18] a position echoed by an ACLU-sponsored group. A shift from this policy began with the reforms of the La Guardia administration attested to by then Assistant Program Director Seymour N. Siegel in 1936: "With the accession of the present Fusion Administration in New York City, WNYC's censorship policies have been materially liberalized, although the heritage of past years still persists to a degree."[19]

The Beginning of the End

Bohnsack's tenure was challenged when the reform-minded La Guardia administration came to power in 1934. By the end of "the little flower's" first term, he was effectively replaced by Seymour N. Siegel, who had initiated several programming innovations. In 1938 the station came under the leadership of Morris S. Novik. Bohnsack had been brought up on charges of being absent without leave and a failure to cooperate. His efforts to appeal the dismissal failed.

It would be easy to conclude that Christie R. Bohnsack was only a Tammany hack doing the bidding of his political masters. Just two months after his leaving WNYC, the National Democratic Club gave him an honorary dinner attended by significant political and media leaders. He was a dedicated party man, even using his vacation time in 1928 to do advance logistics for Al Smith's presidential campaign among other work over the years. Still, he must have been well organized and resourceful to keep up this juggling act for as long as he did with negligible funds, although it appears he wasn't creative enough. Radio proved to be much more than a broadcast lectern, recital stage, and event venue. The medium had progressed and become more sophisticated.

The appointment of Frederick J. H. Kracke to run WNYC's parent agency, the Department Bridges, Plant, and Structures in the new La Guardia Administration had Brooklyn columnist John A. Heffernan confirming that WNYC's shortcomings stemmed largely from City Hall while arguing that radio drama was the key to turning things around.

I hope Commissioner Kracke will do something to aid the staff of WNYC make their station what it ought to be...The trouble with that station has been that Mayor Hylan, who instituted it, used it mainly as a sort of personal advertising bureau, thus rousing antagonisms, and Jimmie Walker needing no advertising bureau and being himself a showman, neglected it, while Mayor O'Brien had no use for it at all. Consequently, Director Bohnsack was thwarted always in his effort to make the station a valuable cultural agency. It should be that and there is enough in the city government to make highly interesting and attractive programs. I think Mayor La Guardia will recognize that fact; that the schools may be dramatized and the works of the hospitals and other institutions brought into closer touch by dramatization with the taxpayers. If Bohnsack, who is himself an excellent showman, had the play he should have had, these institutions would yield thousands of little dramas of intense interest to the men and women who pay for them.[20]

Bohnsack was indeed a showman, but it would take much more than radio drama, (which did become more prominent) to pull WNYC out of its programming rut. Until 1933, the station's funding covered only staff salaries. There was no room in the budget for talent or remote telco lines.[21] It's here that the federal Works Progress Administration would play a significant role in the coming years. Meanwhile, the new Mayor had campaigned on a platform that included shutting the station down to save taxpayer dollars. The day after Heffernan's hopeful column ran, La Guardia swore in Seymour N. Siegel as WNYC's new assistant program director and sent him across the street to shut down the station. Fortunately, Siegel saw its promise, stalled for time, and the Mayor put the station on probation. At the same time, a blue-ribbon panel of broadcasters studied the situation and made recommendations to La Guardia. It should also be noted that the much younger, Ivy League-educated, and energetic Siegel was the son of a Republican judge and former Congressman, who was also the Mayor's long-time friend. But no matter how innovative, Siegel would always be "the kid" in La Guardia's eyes, prompting the Mayor to turn to a seasoned political ally with a known track record in radio. Morris S. Novik would pick up what Siegel initiated and a new era for WNYC began.

____________________________

[1] "Bohnsack on Job as Whalen's 'Voice', " The New York Evening Post, December 20, 1930, pg. 15.

[2] Ibid.

[3] "Broadcast Studio on Strand Stage," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 22, 1925, pg. C6.

[4] Neuman, Herman, "Memoirs of a Broadcaster," Stadium Concerts Review, September 1962, pg. 43.

[5] Fagan, William J., "N. Y. Station Has Unique Remote Control Studio," United Press, The Utica Observer Dispatch, September 2, 1925, pg. 14.

[6] "Broadcasts City's Charms Tonight," Asbury Park Press, June 29, 1925, pg. 2.

[7] O'Loughlin, Edward T., "WNYC Broadcasting Back in Hylan's Day," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 20, 1949, pg. 34.

In an earlier newspaper column, O'Loughlin wrote in detail about the special variety 'night' broadcasts. He said they were inspired by Brooklyn Borough President Edward Riegelmann's pitch to Bohnsack for the first of the series on Brooklyn and airing December 4, 1924.

Riegelmann was in charge of the work. He gave the ideas to Director Bohnsack who furnished the professional and mechanical background and with the Borough President as impresario we all set to work and produced an evening of fun and instruction which made our borough known from Block Island to San Francisco and from Canada all the way to Venezuela. More than 4,000 telegrams, letters and phone calls reached the station as a result of the first program. And it became the forerunner of a hundred others, in many of which Riegelmann took an interest and which served to put the selections boosted on the map and to make WNYC extremely popular. (O'Loughlin, Edward T., "O'Loughlin's Column," Times Union, May 3, 1935, pg. 22).

[8] "Listeners Learn Much About Their City," New York Evening Journal, August 24, 1925, pg. 10

[9] New York Evening Post, December 20, 1930, pg. 15.

[10] Testimony of Christie R. Bohnsack, "City of New York v. Federal Radio Commission," (D.C. Circuit), November 16, 1928, Government Printing Office. 1928, pg. 232.

[11] Clip of unnamed columnist, The New York Democrat, May 20, 1933. James Michael Curley Scrapbook, Internet Archive, Pg. 210.

[12] O'Loughlin, Edward T., "O'Loughlin Recalls: Bohnsack's Welcome to the Liner Bremen," The Brooklyn Eagle, December 16, 1949, pg. 7.

[13] "Air College Begins Lecture Courses," The New York Times, March 15, 1927, pg. 28.

[14] "Radio Lectures to High Schools WNYC's Project," The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 10, 1929, pg.

[15] "Full Time or We Quit Air, WNYC's Stand," Radio World, May 28, 1927, pg. 15.

[16] Time Magazine, December 12, 1927, pg.20

[17] Thomas, Norman "How to Win the Radio from Reaction," The New Leader, May 22, 1926, pg. 4.

[18] Landry, Robert J., This Fascinating Radio Business, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, New York, 1946, pg. 125. See also: Better Late Than Never, A Talk WNYC Censored in 1934.

[19] Siegel, Seymour N., "Censorship in Radio," Air Law Review, January 1936, Vol. 7, No. 1, (1-24) pg. 21.

[20] Heffernan, John A., "Old Friendships Renewed, As Kracke Takes Hold," Brooklyn Times Union, January 2, 1934, pg. 6.

[21] Scher, Saul Nathaniel, "Voice of the City: The History of WNYC, New York City's Municipal Radio Station 1924-1962," NYU PhD. Thesis, 1965, pg. 128.