The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

The City's Latest Proposals to 'Reimagine' the BQE

The New York City Department of Transportation has three new design concepts for what Mayor Adams calls a "reimagined BQE Central," referring to the notorious corridor of the Brooklyn-Queens-Expressway that houses the triple cantilever. These new designs aim to connect the community to the waterfront and improve public space. But will the reimagined BQE Central be a two-lane highway or a three-lane highway? Meera Joshi, NYC deputy mayor for operations, walks us through these proposals and tells us what's next for the beleaguered expressway.

[music]

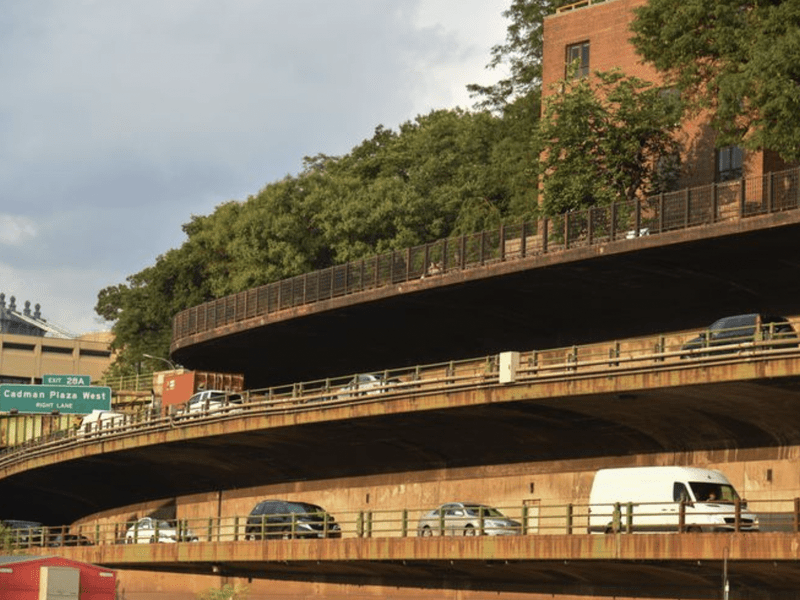

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. We'll check in on the city's plans for a notorious section of the Brooklyn-Queens-Expressway, this section of the BQE known as BQE Central, as many of you unfortunately know too well stretches from Atlantic Avenue to Sands Street in Brooklyn Heights and is home to the decrepit, famous infamous triple cantilever. If you live in that area or pass through it, you know that the triple cantilever limits access to the waterfront and to Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Now the New York City Department of Transportation has three new design concepts for what Mayor Adams calls a reimagined BQE Central, all of which aim to connect the community to the waterfront and improve public space while also making sure that the highway itself doesn't fall apart. The DOT is also studying whether the number of traffic lanes in this corridor of the BQE should be two or three in each direction.

We'll walk through the city's new design concepts and talk about what's next for this beleaguered stretch of expressway with Meera Joshi, the New York City Deputy Mayor for Operations. Deputy Mayor, thanks for coming on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Meera Joshi: Thank you so much for having me.

Brian Lehrer: The new design concepts I see have been nicknamed The Stoop, The Terraces, and The Lookout. Do you want to briefly walk us through each of them?

Meera Joshi: Sure. The commonality with all three of them is that we'll combine making an engineeringly sound cantilever or a new cantilever, new highway section with increasing public space as well as increasing access for people that are walking in Brooklyn to the beautiful Brooklyn Bridge Park. All three of them have different ways to connect from the promenade level then straight down to Brooklyn Bridge Park. Some of them, The Terraces is by a series of steps. The Lookout focuses on just two entry points that are two cascading hills and The Stoop enlarges the width of the promenade and has one entry point for Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Brian Lehrer: What are the city's priorities here, biggest priorities as you weigh which one would be better than which other one and what the trade-offs are?

Meera Joshi: Thank you. Our biggest priority is to making sure that we have a sound and swift construction project that maximizes the priorities that we think are in the public good. That is ensuring that we are doing a climate-forward plan, that we're doing a plan that enhances the neighborhood, increases connectivity, increases public space, and also acknowledges that this is a main traffic and freight corridor and so the structure needs to be sound.

Brian Lehrer: On it being climate-forward, the number of lanes and therefore, how much car and truck traffic presumably passes through there, is city halls positioned that this corridor should be three lanes in each direction not two? Mayor de Blasio, as I understand it, narrowed that stretch of the expressway from three lanes down to two, but last month, the Department of Transportation announced that it would revisit the number of lanes even though as Council Member Lincoln Restler said to Queens New York, “Every elected official representing the triple cantilever section has been crystal clear with DOT, we want to say a two-lane solution.” So what's your position?

Meera Joshi: Yes, that's a great question. Just to give some background, this is a 1.4, 1.5-mile stretch of the overall BQE, which is primarily three lanes. We had the really fortunate experience of having it reduced to two lanes in the cantilever section so as a city, we got to experience what a two-lane reduction of this normally three-lane section is like. Council member Restler and many others have made it very, very clear with us that they are interested in keeping it at two lanes.

We are embarking on a data-centered traffic analysis essentially to understand what the traffic patterns are with two lanes and what the traffic patterns are from the data that we have when it was three lanes. Where the traffic goes, any delays in traffic, any efficiencies in traffic, that information that the traffic sensors pick up will be analyzed and it'll go as part of our application for federal grant money, for reconstruction and we’ll work with the FHWA to understand and evaluate both of those scenarios, two lanes versus three lanes.

Overall, as a city and as a nation, I think it's very clear we are looking to make sure that we are not increasing car dependence and increasing truck dependence as a society. That's the hierarchy theme that we look at this project with. The devil's in the details and we also want to make sure that we're objective about this process, which is why we are certainly doing a ton of value. We want to hear the community members' feedback, the electeds that are in the cantilever section as well as electeds and other parts of the city and ultimately integrate that with the actual data of what are the traffic speeds, what's the impact on local streets, what are the efficiencies we've gotten and how can we best proceed forward knowing that our overarching North star is we do want to reduce our dependence on trucks to move our freight and cars to move our people.

Brian Lehrer: Does the Department of Transportation believe it's possible that more lanes will actually reduce traffic?

Meera Joshi: That's a great question. Again, it's a 1.4 miles and it is the question of in this demand. If you expand something, will you actually make more traffic come on rather than less traffic? I think the question here really is the flip. And that is have there been a spillover effects of two lanes that we need to address and mitigate against if we proceed with two lanes? We're not doing this in a vacuum. There's a lot of things that come out about how we can do work and we are doing work around the city that affects the two-lane three-lane conversation.

For example, last-mile delivery, looking at micro hubs so that trucks don't have to go quite so far into the city, congestion pricing, our marine highway. I'm proud to highlight that we did win federal dollars to do upgrades to six landings around the city, four in Manhattan, one in the Bronx, and one in Brooklyn that will allow us to use those landings for delivering freight. That's the kind of complimentary work that we have to make sure coincides and is done in parallel with our BQE reconstruction work.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your BQE calls for Deputy Mayor Meera Joshi at (212) 433-WNYC, (212) 433 96929, and your tweets @BrianLehrer. Just staying on the two-lane or three-lane question for a minute because it's such a hot button. From what I've seen, the city says it's open to a two or a three-lane highway and has taken community input as you say but that the city has already put out stats to show that having it at two lanes right now has slowed traffic 30% to 50% in places in terms of the speeds that cars can travel which seems to indicate that you're leaning in the direction of three lanes to have traffic be able to go faster even though people in Brooklyn Heights wanted to be two lanes, less pollution.

Meera Joshi: Yes, so we did put out some very preliminary information about data that was collected and the process that we're going through now is gathering data that's very recent. We have a current snapshot of that. The other process that is really important is there's mitigation. Just because there may be traffic impacts to two lanes we also need to understand what are the mitigations, what are the other things we can do to try to lessen those impacts. It's really two things. One, the data analysis we're doing now, which is going to incorporate spring 2023 data will be a better snapshot, and more comprehensive snapshot, and a more recent snapshot of what's actually going on. We're doing that work in conjunction with New York State.

This really helps the federal government when they evaluate because they are going to get a lot of feedback and they should get a lot of feedback about two versus three but having that recent data analysis will be really important. Then we can go and work through with our- -state and federal partners to the extent that there are impacts that need mitigation, what are those mitigations and how much will they help

Brian Lehrer: Gav in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Gav?

Gav: Hey. Hi. I heard you talk about this. I got to say, I live at 1 Brooklyn Bridge Park, which is the building in Brooklyn most affected by the BQE, the Cantilever Rebuild Plan and everything. I got to say Brooklyn Heights, where I live and I've lived since 1982, we invented Nimbyism. What? Everything reducing the repair plan and the reduction of lanes just forces all the traffic onto Third Avenue, Fourth Avenue, Sunset Park, and everything, which are neighborhoods that aren’t Brooklyn Heights, as we know.

We can talk about how this was bad when Robert Moses did this in the ‘50s and whatever. Here it is, it is the life bread. Every hipster who wants to eat quail eggs in a restaurant somewhere, they get there by truck. That's it. We have to suck it up and absorb it and go back to three lanes on the BQE. The life we love in New York doesn't work without it. For us in Brooklyn Heights, the affluent people of Brooklyn Heights to say, make it some other neighborhoods problem is. I can't stomach that.

Brian Lehrer: Gav, thank you very much. Deputy Mayor?

Meera Joshi: Thank you for your candid comments. You're right, most of the nation gets everything they use by truck. In New York, it's even more acute. 90% of our goods are supplied by truck. Every time we hit that ‘add to cart’ and it appears on our doorstep, there's lots of other consequences to that action. There's traffic, there's also a whole labor consequence and a world of independent contractors that are providing this service to us that surely needs to be looked at.

You're right. There are follow on effects of having two lanes. We have talked to people outside of the Brooklyn Heights community as well. I want to say one of the big things that's come up and why people say, ‘I'm on the BQE not because I love being on the BQE,” is because of lack of transit options in lots of places in Southern Brooklyn. Again, this can't be looked at in a vacuum. That's such an accurate statement. We have leverage in the city that hopefully we can use, especially with the MTA, to address some of the transit or the lack of transit options that force people onto the BQE in the first place.

Brian Lehrer: Well, isn't there good evidence from a lot of different places over time that widening highways often makes traffic worse, more cars and trucks are attracted to them, more lanes could equal worse traffic, slower speeds, as opposed to necessarily alleviating that?

Meera Joshi:: Yes, that has been the experience in some of major highway reconstruction and then on the flip side, when there's been roadway diets. I was trained as a lawyer and we used to always say, if you get another extension from the court like a sponge, you'll use up every second. It's not like you'll say, “I only needed two days, but they gave me a week, so I stopped working after two days.’ You'll use the whole entire week.

That is part of the evaluation process. When you look at the three-lane and two-lane statistics, are we actually going to add more traffic and are we then going to be undermining some of this other work that we're going to do in parallel, which is trying to divert traffic and divert freight from the BQE? I think that the other reality is it is a commercial corridor and so we can't be only looking at those that are thinking about that journey in that one mile. It is the entire corridor.

On that topic of entire corridor, this whole project is entire corridor. The cantilever in some ways was the only part of the BQE that was actually hidden from communities. It's the other sections of the BQE that are three lanes that are also very, very visible for communities. They're visible through the pollution, they're visible through the traffic, but they're also visible in a really devastating way as they actually happen to be some of our least safe intersections especially underneath the BQE in the city.

We're in parallel with looking at how we reduce traffic on the BQE, are also looking at improvements we can make along the corridor now to improve safety and public space, as well as working with those communities. We've given out some grant dollars both to North And South community groups to talk about long-term vision for the entire corridor, and ways that we can reconnect those communities that really have been ripped apart in very, very visible ways.

Brian Lehrer: We have that one caller from 1 Brooklyn Bridge Park. Here's a caller I think from a little further out on the BQE route. Erick in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Erick?

Erick: Hey, how you doing? Great show. I had a question. Has there been any talks to the people of the Nature Development? Because you've mentioned Sands Street and Sands Street is closer towards the Nature Development in the neighborhood than it is to Brooklyn Heights. Has anybody from that neighborhood been contacted or has this plans been brought to their attention? Because you're mentioned constantly, Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn Heights, but this BQE run through Brooklyn Heights in Sands Street is actually more closer to the Nature Development in now Brooklyn Heights. That's my question.

Brian Lehrer: Great point, Deputy Mayor?

Meera Joshi:: Yes, exactly. There has been some outreach and I will get back to you on the-- if you want to give your name and contact information to Brian Lehrer, we'll make sure to follow up to give you the calendar of the outreach that's been done, but also welcome your suggestions on further outreach that we could do in that area.

Brian Lehrer: All right, Erick, if you want to hang on and leave your contact information, we will take that from you and it sounds like you'll be getting a call from the Deputy Mayor's office, which is great. Well, speaking about which communities have input to these decisions, I understand that last Friday City Hall hosted a private meeting with 70 South Brooklyn elected officials and agency heads about the BQE. What was the purpose of that meeting? Was it to rally support for a three-lane highway?

Meera Joshi:: We hold regular meetings with electeds. There's a group led by council member Lincoln Restler of electeds that have both rallied to the state government, asking them to be more involved in North and South and also written their letters of support in front of two lanes. We regularly have meetings with them. In fact, we put them at a regular cadence. We also get lots of requests for meetings. We got a request from electeds in the Southern area of Brooklyn for meeting as well as some of those in Staten Island.

I'm not sure I'd call it private with 70 electeds on it. In fact, there was a representative-- or actually Assembly Member Joanne Simon was on that as well. She's been part of our other meetings with those that are more in the cantilever community. Really, what happened during that is there's lots of discussion between two and three lanes. Some people advocated for two lanes for the benefits that you described around there, are we going to risk induced demand? Many people argued for three lanes for reasons that were identified by the first caller that you had on is what are the effects on the communities North and South?

I think it was really important because other issues were raised that haven't been so front and center and really should be. Some of the transit desert problems in South Brooklyn, several people raised that, that they don't feel they have much of a choice other than to get on the BQE because of lack of bus and subway service. As well as several people raised this, this is a huge construction undertaking in New York City, and this is an opportunity to make sure that we expand our MWBE participation in that kind of work. That was another focal point of the conversation.

We'll continue to speak with electeds and community groups in many different fashions. Sometimes they're in-person meetings, sometimes they're virtual, sometimes they're us going out. We certainly are going to leave the door open and we'll continue our regular cadence of meeting with this core group of electeds that have really rallied around some of the two-lane benefits.

Brian Lehrer: Joe in Huntington, who owns a trucking company, he says you're on WNYC. Joe, thank you for calling in. We really appreciate it.

Joe: Hey, how you doing, Brian? I called once before, had a delightful conversation with you.

Brian Lehrer: Good. I remember.

Joe: My issue would be if congestion pricing is implemented, volume on the BQE will increase by trucks going into Manhattan and going to New Jersey. There's only two way to get to New Jersey right now from Long Island,- -which is the George Washington Bridge, and the BQE over the Verrazzano through Staten Island. Also, going to Staten Island, there's only really one way to get in with trucks. The volume on the BQE will definitely increase if congestion prices are implemented for commercial vehicles.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Let me ask you this Joe, because to some people, depending on where they live, they may find it a little surprising. If I hear you correctly, trucks going from Long Island to New Jersey, which sometimes go through Manhattan, right now, of course, that would go-

Joe: Oh, absolutely.

Brian Lehrer: - into the congestion pricing zone, but people may think, “Why would I ever drive through Manhattan if I'm really trying to get around it?”

Joe: Because at six o'clock in the morning, it's a very nice delightful ride from Long Island to the Midtown and it's quite interesting. You have joggers, you have people just getting coffee, you have a ton of people just doing things that they would do other than working prior to working. You have your commuters, maybe on bicycle, but it's an interesting ride. It's believe it or not, relaxing, but that's from six o'clock to 7:30. After that, I don't think you want to be in Midtown.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Thank you. Joe, keep calling us. Well, Deputy Mayor, he brings another element into it, and that is congestion pricing. We've had this conversation on the show with respect to the Cross Bronx Expressway, that some of the congestion pricing models would increase traffic and congestion and pollution there, same thing with BQE?

Meera Joshi: Yes. I think there are several models that are being considered. I do want to just say that is the wonderment of being a truck driver is you get to see cities in the nation at times and in places that the rest of us don't so it's nice to hear that. It does depend on what model is ultimately selected, and things like whether credits are used or not. You could end up with a scenario where additional truck traffic is driven to the BQE.

On that front, it as a commercial corridor, we have to think about ways that we can make either use of our marine highway so that it's less a highway-dependent for freight travel, and also reducing some of the other non-truck traffic that's on the BQE because trucks, lane by themselves with professional drivers are very efficient. It's the mix between trucks and cars that becomes not only more dangerous for everyone involved, but also creates more of a congestion problem because they have different driving styles. Trucks don't tend to weave in and out but cars do so there is those issues.

Ultimately, we need to think about that we are so heavily dependent on trucks as a city, are there easier ways for us to make those last-minute connections, and those ways for people to get through to New Jersey that aren't so dependent on our highways?

Brian Lehrer: On some of the route being a transit desert, a listener tweets, "Any discussion of making the third BQE lane for a mass transit like a tram, you already have the right of way?" writes this listener.

Meera Joshi: Yes. That was one thing that we raised in our outreach, if it was an express bus lane, is that a way to help people, especially in parts of Brooklyn to get more effective transit? That's certainly something that as we discussed in terms of like, mitigations, that we have put on the table.

Brian Lehrer: As we--

Meera Joshi: I just saw people-- I don't mean to interrupt.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Meera Joshi: I’m just going to take two seconds if it's helpful for the listeners to understand the timeframe, because everyone's like, "Well, when is this? You’re moving too fast, you're moving too slow." I just want to give a little bit of a chronology. We are in the process of finalizing our outreach and starting our collection of data for sensors in the ground on the actual traffic.

We'll be modeling that and analyzing that. In May, we will submit for Federal grant opportunities. The thing that is so different about the infrastructure bill and the leadership of our President Biden and Secretary Buttigieg is that the emphasis now is on shovel-worthy projects as opposed to-- not as opposed but not as prioritized shovel-ready projects. They really have conveyed this to us very frequently is that what is the impact to the surrounding area and the necessity for this project?

We will then in September likely issue what's called our notice of intent to do an environmental review that is required for every federally funded project, and that takes two years. Then in 2027, is when we'll look at starting construction. That's the overall timeframe. A couple of things that could help accelerate that, we're right now arguing at the state level, that the city be given the option to use a tool called progressive design-build, which allows us to do construction much faster, especially for very complex projects like this one.

We're certainly looking into how we can use barges for bringing on equipment, for staging and for modular construction. That's where you're building pieces off-site and dropping it in as it's done all over the world now. These are the kinds of advancements that would help us accelerate what might have been a much longer construction schedule.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I know these things take time, but even that timeline that you just laid out, probably has a lot of people in the area thinking, "Oh, I have to live with this for years more." How can people give their feedback, last question, on these design concepts?

Meera Joshi: On the design concepts, if you go on DOT's website, there is areas there to add feedback. We'll make sure, Brian, after the show, I get you all of those right contacts, so if you want to publicize them in any of your future shows, please do.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Meera Joshi: We welcome the feedback. I'm really actually very excited about the level of engagement we've had with all of the outreach sessions we've done in-person and virtually, thousands and thousands of people, and an overarching feeling that it's time to, and this is on message for our mayor, I don't think he put them there. He didn't set them up to say this, but they're basically that sentiment, it's time to just get this done.

Brian Lehrer: Well, you're in the middle of this, we can tell from our callers and from our tweeters that people are on numerous sides of this issue with various competing interests and push and pull because there’s no-- if you solve one problem, you create or exacerbate another, so this is a tough set of decisions. Deputy mayor, Meera Joshi, we thank you for coming on and talking through the state of the BQE with us and our listeners. Thank you.

Meera Joshi: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.