With growing pressure to reduce the number of people held in jail because they're too poor to post bail or because of delays in going to trial, many criminal justice advocates believe New York state is on the brink of criminal justice reform in 2018.

"I’m keeping my fingers crossed that this year the governor will return to that issue," said John Savarese, chairman of the New York City Bar's task force on mass incarceration. "There’ve been some signals that he will make bail reform an important part of the legislative package this coming term."

Those signals include meetings this year between the the governor's office and advocates, according to sources. Though Cuomo's office did not return a request for comment, many observers believe the governor will propose changes to the state's bail statute in 2018, after efforts in 2016 and 2017 failed. This year, activists believe, the timing is right, now that they've honed their message.

Here are three changes they're hoping to see.

Bail Reform.

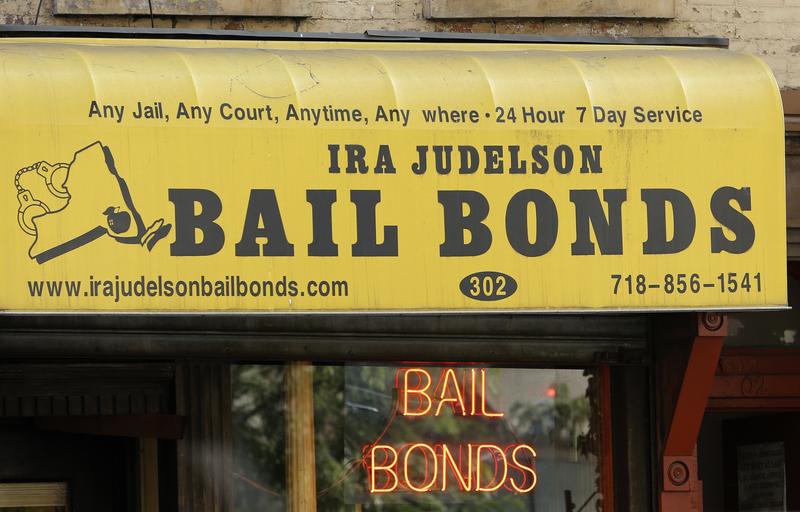

In New York, bail is based on a defendant's risk of flight. Gov. Cuomo has previously proposed basing it on whether a defendant is considered dangerous, like in New Jersey, which uses a risk assessment score. But defense attorneys have vigorously opposed that - arguing it could lead to other forms of discrimination.

Last month, more than 100 community and advocacy groups across the state signed a letter to Gov. Cuomo urging him not to add dangerousness to New York's bail statute. They argued that predicting whether a defendant is dangerous "will further exacerbate racial bias in our criminal justice" system, and even lead to more people being held on bail.

Instead, they believe judges should consider other forms of bail besides cash or an insurance company bond. These rarely used options could include partially secured bonds (which require putting down less cash).

They also want to encourage judges to avoid setting bail whenever possible. Insha Rahman, project director at the Vera Institute of Justice, said judges in New York City frequently release people on their own recognizance, but other jurisdictions are more punitive.

"Many judges think, well, 'my job is to set bail,'" she explained. She said the legislature could require judges to release people who don't pose a flight risk, especially if they're charged with misdemeanors. A study by Vera found that up to 89 percent of the jail population in some counties consists of people charged with misdemeanors. By contrast, the number is just 10 percent in New York City.

Speedy Trials

There was tremendous hope that New York would pass a faster trial law in 2017, after an agreement was reached between the Assembly and Senate. But it fell apart.

The law was named after Kalief Browder, who served almost three years in the jail complex on Rikers Island because he couldn't pay $10,000 in bail. He later killed himself after his release.

Browder spent that much time behind bars because trials take so long in New York. Although state law requires a trial within 180 days for someone accused of a felony and 90 days for a misdemeanor, prosecutors can get around that if they tell the court they aren't ready. (District attorneys worry faster trials would lead to a "legalized jailbreak.")

Many advocates are hoping Kalief's Law will be revived in 2018.

Discovery Reform

Despite a 1964 Supreme Court ruling that requires prosecutors to turn over evidence, or discovery, that could help a defendant, New York State allows them to hold onto a lot of that material (including police reports and witness lists) until the trial begins.

This year, the state's chief judge, Janet DiFiore, issued a new rule requiring prosecutors to turn over exculpatory evidence before the trial starts.

Rahman, of the Vera Institute, says the state legislature should go even further by requiring prosecutors to turn over more evidence. "We know people are taking pleas without having seen the discovery in their case," she said.

Having the evidence earlier could also help a defendant spend less time in jail.

Gabriel Sayegh, co-executive director of the Katal Canter for Health, Equity and Justice, said all three of these issues have generated a lot more discussion in 2017 than in previous years.

"We’re hoping that that translates into very clear proposals in the governor’s State of the State.”