Hypothesis

Hypothesis

The Gray Whale Sneaks Back into the Atlantic, Two Centuries Later

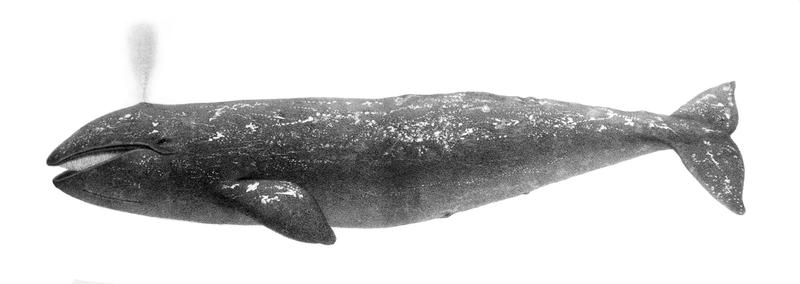

Two years ago, tour boats taking passengers to look for dolphins off the coast of Namibia saw a strange sight: out of the water, a humped, bumpy dark gray back rose up, striped with scars and spotted with barnacles.

It looked like a gray whale. Except gray whales had been extinct in the Atlantic Ocean since the 18th century.

Liz Alter, an assistant professor of biology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, says it actually wasn't the first sighting. In 2011, a gray whale was spotted in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Israel.

"It came as huge shock to me and other marine mammologists," she recalled. "Many of us didn't believe it at first. There were even suggestions that maybe the picture had been Photoshopped. But gray whales are extremely distinctive. When you see a gray whale there's basically nothing else it could be."

Gray whales are considered "ecosystem engineers" — species that reshape the world they live in, like beavers, ants and coral. Like bulldozers — or giant earthworms — gray whales feed in the mud, creating huge holes and stirring up nutrients stuck on the ocean floor so that other creatures can eat them. The population in Pacific remains strong, but in the Atlantic they have been long gone.

Until these two sightings.

Researchers confirmed it. The creature spotted off Namibia was indeed a gray whale. But researchers still assumed it and the one spotted off Israel were anomalies, possibly whales that got lost while feeding.

Now Alter and her team have released a paper that sheds light into what may be going on.

Alter and her team were able to access an unusually large collection of bone fossils that had been collected by a fisherman over a long career and who had stored them in his garage. They radio carbon-dated the samples and compared the genetic data to Pacific gray whales. The researchers hoped to pinpoint when the two populations had branched.

"We found to our great surprise that Atlantic and Pacific gray whales were not separated by millions of years like other whales," Alter said. "But rather our genetic evidence showed they had made several migrations over the past 100,000 years or so. And the period in which they migrated corresponded nicely to times when the oceans were a bit warmer, when the ice cover was less and the Bering Strait was open."

Basically, Alter said, "Gray whales started moving from Pacific to the Atlantic as soon as climate conditions permitted them to."

Now, with the Arctic currently receding, Alter says it will become more and more likely that gray whales will again find their way into the Atlantic.

"I don't expect that we'll see a brand new population of gray whales in the Atlantic anytime in the very near future," she said, "but it shouldn't surprise us if we start to see steady trickle of gray whales arriving in the Atlantic."

Alter says what amazes her is getting new information from bones more than 45,000 years old.

"Working on ancient samples is really exciting," she said. "You get this view into the past that you've only been able to hypothesize about. Having direct evidence of what was going on in the past is super exciting as a biologist. It's all made possible by technology that wasn't there 20 years ago."

Hypothesis is written and produced by Alec Hamilton and edited by Matthew Schuerman. Sound design and engineering by Liora Noam-Kravitz. Original music by Josh Burnett.