It was a typical day in New York’s busy immigration court. On December 14th of last year, dozens of immigrants, children and attorneys were packed into Judge Oshea Spencer’s cramped courtroom on the 14th floor of Federal Plaza. Each immigrant had come for a short procedural hearing as part of the long process before their trial.

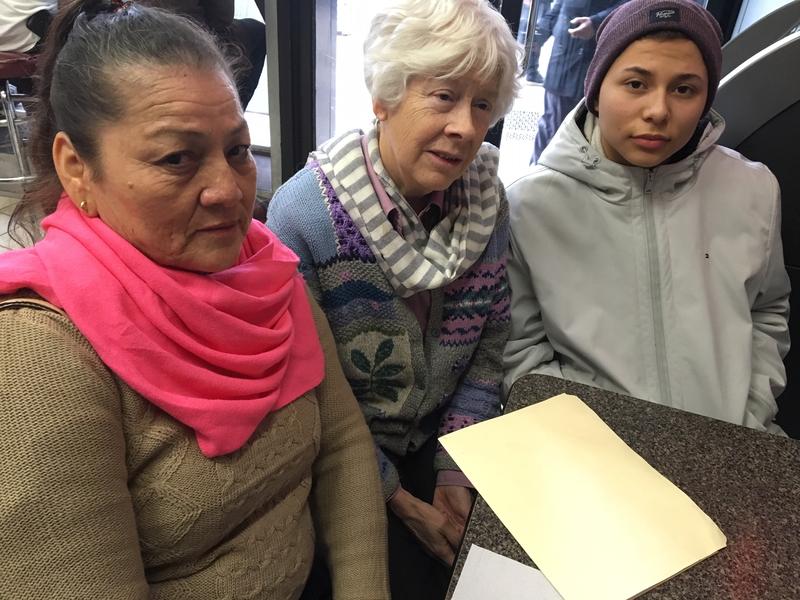

Attorney Anne Pilsbury of Central American Legal Assistance was representing Esperanza, a Honduran mother with a teenage son named Josue. She asked that we not use their full names. They crossed the U.S.-Mexico border last summer.

Pilsbury and her clients had just been to Spencer's courtroom less than a month ago. It would normally be a few more months until they had to return.

"Judge, I don't understand what happened here," Pilsbury said, as soon as the case was called. She sat at a small desk with her two clients. A government attorney sat at another desk a few feet away.

Spencer explained the change.

"All of the cases that are being designated as FAMU, family unit cases, are being placed on a different calendar."

In other words, family cases are moving much faster than usual. Esperanza was scheduled to have her asylum trial in May. But Spencer wanted it done even earlier. She offered Pilsbury March 26, 27 and April 2nd as possible dates for the trial, also known as a final hearing.

Pilsbury apologized to the judge and explained that her nonprofit was overwhelmed with cases going to trial.

"It would be a violation of due process for me to take another final hearing any sooner than what we had already agreed to."

Spencer paused and replied that keeping a trial date in May "does not comply with my calendar," but added, "since that was the date that was previously given to you, and your organization is strained, I will continue the May 14th, 2019 date."

This back and forth over expediting a trial that was already scheduled to occur in less than a year illustrates the tremendous pressure immigration judges are under to finish cases. Last November, the Justice Department – which controls the immigration courts – told judges in 10 cities, including New York, to complete all cases labeled family units in a year or less. This policy was announced in a memo. No reason was stated for singling out family cases. When WNYC asked the government asked why, we were referred back to the memo.

Pilsbury has her own theory.

"They have decided to prioritize immigrants that enter with children, and do their cases fast," she stated. "And I think they’re doing it on purpose to try to deter people from coming."

Why Asylum Cases are Difficult

Like many immigrants seeking asylum in the U.S., Pilsbury's client, Esperanza, had no idea how the immigration courts work when she left Honduras last summer. She said she just wanted more for 16 year-old Josue. She saw death in his future if they stuck around. Josue said he was approached by gang leaders who wanted him to sell drugs at school, and was once threatened at gunpoint.

Stories like these are common among the Central American families seeking asylum, and a record number of families are crossing the border lately. But kids like Josue often don’t have police reports to back up their claims because, as they explain, there’s no point. The cops have been bribed by the gangs.

Pilsbury has been an immigration lawyer for 30 years and said this is why asylum cases are tough to prove in less than a year, as the government now demands.

"To win an asylum case you have to try to find statements, testimony, death certificates, news reports from the home countries. Then you have to translate them. And then there’s this tedious process of preparing documents for court," she explained. "It’s not something you can whip out overnight."

Reducing the Backlog

And yet, it's understandable why the government would want to move things along. The main New York City immigration court has a backlog of more than 114,000 cases, which typically take years to finish. Former Immigration Judge Andrew Arthur said there's a benefit in fast-tracking the family cases, "if the adjudication of those cases would enable you to identify valid cases, individuals who should be granted asylum."

Arthur is now a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that wants to limit immigration. By granting asylum to worthy cases and denying it to those that aren't, Arthur predicted a "deterrent effect" on families "considering taking that dangerous journey to the United States."

The Obama administration also fast-tracked the family cases in 2014, after another surge in migrant families and unaccompanied children. The memo issued by the Justice Department in November, announcing the new family unit policy, said this prior experiment actually lowered case completion rates and "did not produce significant results." It said it's now trying a "more targeted and dedicated approach."

That's probably why so many family cases are being assigned to new judges like Spencer, who started work last October. These judges don't have as many trials scheduled years in advance. But when a family case gets prioritized, that means another immigrant who's been waiting years for their trial could get bumped, forcing them to wait even longer. A lot of immigration judges in New York are scheduling trials in 2021 and 2022.

Some immigrants don't mind waiting longer if their cases are weak, or if they're able to work in the meantime and save money. But others are desperate to finish their trials. When an asylum trial is postponed, memories can fade and witnesses may not be available.

Central American Legal Assistance, which Pilsbury founded in response to the Salvadoran civil war's refugee crisis, doesn't charge a fee and takes walk-in clients. Its front desk is very busy now because of the huge number of migrant families crossing the border. Attorney Rebecca Press said 20 trials were scheduled in February and March, but then three more were suddenly added when the government decided to expedite family cases. This put a strain on the organization's small team of attorneys. She also said it's unfair to bypass everyone else who's been waiting to go to court.

"I cannot think of a legitimate reason to accelerate only one group of people. Only one group of people from a certain region of the world," she stated.

One attorney, who works elsewhere and didn't want to be named, said this is why she objects every time one of her family cases is expedited. She tells judges it's prejudicial to schedule Central American families ahead of everyone else, putting this on the record in case she wants to use it for an appeal.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review, the Justice Department agency that controls the courts, said it's been adding new judges to speed things along for everyone. Since the beginning of 2017, spokesman John Martin said it's hired more immigration judges than in the previous seven years combined. But there are still just about 450 judges for a national backlog of more than 855,000 cases. And according to the research group TRAC at Syracuse University, just 4 percent of those cases are families.