When World War I began, the U.S. had adopted a stance of political neutrality. By the time it ended, voicing opposition to the war could lead to incarceration. Now, a new exhibit at The New York Public Library traces how propaganda helped change the American mindset through those years.

Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind opens exactly 100 years after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, marking the beginning of World War I. It wasn’t until almost three years later that the United States officially joined its allies — ending Woodrow Wilson’s policy of political neutrality. But even before then, views of what America's role should be were contested around the country and in the press.

“The Lusitania really brought the war home for the first time; we had the loss of 128 American lives. That was sort of the signal moment when Americans woke up and said ‘oh this war in Europe truly does affect our country’,” he said.

He notes though, that much of the reporting on the war came from British and Allied sources. At the outset of the war, Britain had severed Germany’s transatlantic telegraph wire, limiting the news reports to those written by Germany’s enemy. The presence of German Immigrants and their contribution to a neutral stance is explored in the exhibit.

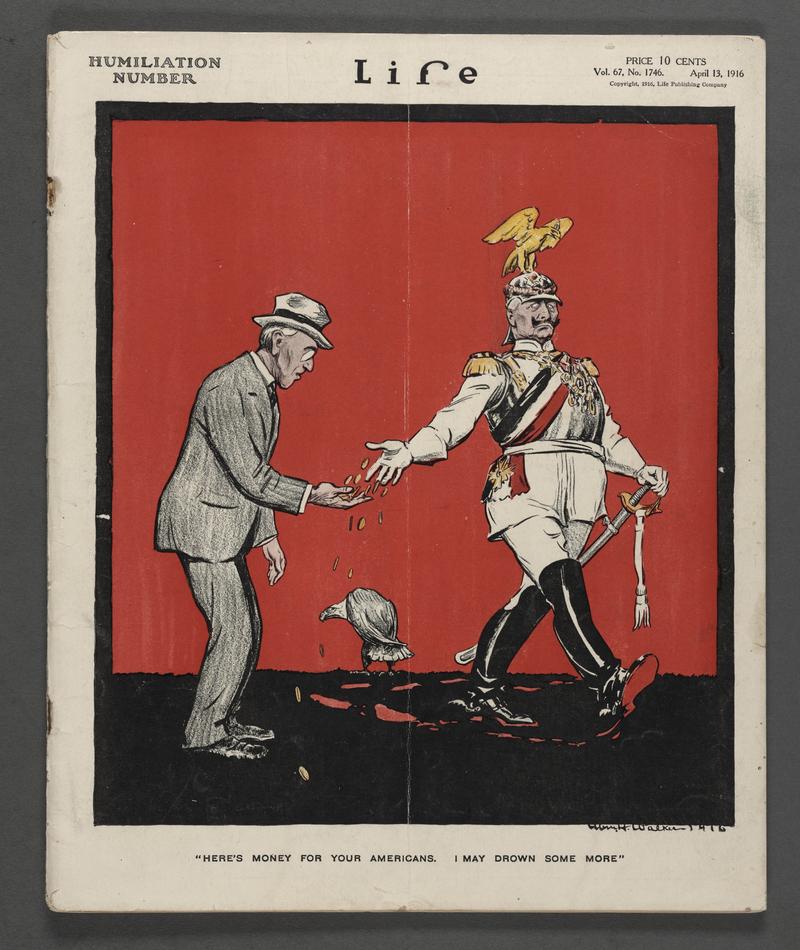

Public opinion changed after the sinking of the Lusitania. Propaganda began to demonize the enemy and play to feelings of fear.

One example is a poster that portrays an apocalyptic scene of New York: the Statue of Liberty with her head knocked off, German submarines approaching a collapsed Brooklyn bridge and lower Manhattan in flames. “It was a very evocative poster," says Inman, "and one that was used very effectively to whip up fear in the American public, to whip up feelings of patriotic obligations that Americans should contribute to the war effort in any way that they could.”

A number of pieces in the exhibit explore the first uses of new technologies, like recorded sound and motion pictures, for propaganda purposes. Wax cylinder recorders, a listening booth for songs of the time and silent films allow visitors to hear and see some of the media from the period.

Inman said that these new methods allowed news to reach people who did not normally read papers and take part in politics. One of the songs that he feels really represents the American experience of the war is George M. Cohan's "Over There."

“It captures that exuberance, sort of the bravado of a young nation asserting itself on the world stage for the first time with those lyrics ‘we’re coming over and we won’t be back till it’s over over there," he said.

The exhibit runs July 28th to February 2015.