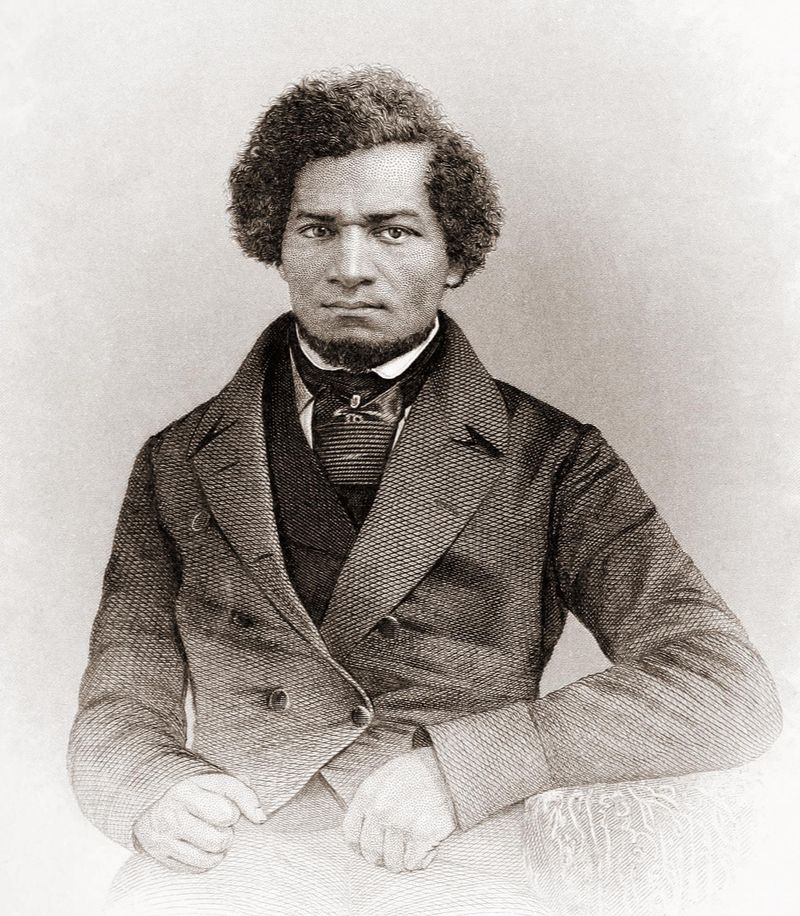

( Engraved by J.C. Buttre from a daguerretotype. - Frontispiece: Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom. New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan (1855) )

[REBROADCAST FROM FEBRUARY 23, 2021] For the second installment of our February “Full Bio” series, historian David W. Blight describes what made Frederick Douglass such an engaging speaker that he became one of the most powerful voices in 19th century America. Plus, we’ll look at how the prominent abolitionist’s views on slavery evolved in the 1830’s and 1840’s.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Today is the 4th of July, and on the show, we're learning about the life of the famed abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, who gave a famous speech examining what freedom really means called What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? You'll hear excerpts from my Full Bio conversation with historian David Blight, author of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

For this segment, we pick up Frederick Douglass's story as he becomes a well-known public speaker. His words and delivery methods were bold and unusual for the time because of their personal nature. To get a sense of the power of his words, let's listen to a reading of one of his most famous speeches that he delivered on July 5th, 1852 titled What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? Here's actor Philip Darius Wallace doing a dramatic reading of the speech for the US National Archives.

Philip Darius Wallace: "You proclaim before the world, and before the world proclaim, we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and have been endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, and that of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet you hold in bondage a seventh part of the inhabitants of your country. The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism a sham, your humanity a base pretense, your Christianity a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad; it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the very foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing."

Alison Stewart: Now, Douglass was not beloved by everyone. Sometimes he was chased and beaten, his home was attacked, and one time in Battery Park, right here in New York City, he was surrounded by a mob for even daring to walk with a white woman. These events never stopped him from traveling the nation and across the pond to England and Ireland to give speeches on the evils of slavery and the importance of abolition. I asked David Blight what void Frederick Douglass filled in the anti-slavery movement with his writing and oratory skills.

David Blight: Well, if it's a void he's filling it is he's not the first, but he certainly became the most prominent former slave, Black American to stand up on the platforms, out in park-like settings, in pulpits of churches, in town halls, and city halls. He became the witness. The former slave who could tell his story of enslavement. Who could tell about the potential psychological destruction of the slave system. The void he filled was that role of being the witness of the actual experience.

Now, I would add to that though, he was much more than just the Black spokesman. He wanted to be much more than simply the exhibit up on the stage. The exhibition up on the stage. Douglass early on became an astute analyst. An analyst of the meaning of slavery, an analyst of the meaning of racism, an analyst of the threat of slavery itself to the existence of the United States, and he became, really very quickly, a master storyteller. He was brilliant at unfolding narratives verbally through oratory.

He is simply a master storyteller, and we see that very early. The first speech for which we have a text comes from 1842. Then we get a few more texts of speeches in the next year or so. Then eventually, by the mid-1840s and into the late 1840s, we have lots of texts of the speeches Douglass delivered. His own texts, and then sometimes those texts as recorded by a journalist. This was now an orator who could do what the Colombian orator had taught him to do, and that is, use your full body. Use the fullness of your voice. Start low but work toward crescendos.

Above all, he was the orator who could take you somewhere. He was the orator who could tell you a story that you are suddenly embodying and you're coming along on a journey somewhere, and ultimately that journey is taking you to some deep moral message that probably will make you hurt. Last point about that, his first few years out on the circuit, in particular 1841, '42, '43, '44, his most popular lecture, his most popular subject, was what became known as the slaveholder's sermon. This is where Douglass would get up and he'd start reading some of those passages in the Bible that are pro-slavery, "Slaves, be loyal to your masters," and so on and so on and so on.

He'd read some of those passages, and then he reads something else from the gospel that would be anti-slavery, but mostly he would start mimicking a pro-slavery preacher in the South. He'd prance around the stage. He'd go into his Southern accents. It was so popular when he would do these that it got to the point out on the circuit that-- The way abolitionists ran their gatherings is they would have four or five speakers, they have a resolution. Each speaker was supposed to speak to or against the resolution. Often, they'd be doing their resolutions and somebody in the audience would just shout out-- I have a number of these examples. They'd say, "Hey, Fred. Do the sermon." He'd say--

Alison Stewart: [laughs] His greatest hits, if you will.

David Blight: Yes. "Do your greatest hit. Sing us the old song." He'd just break into his slaveholder's sermon, and he'd have them laughing and weeping. Of course, the whole point of that slaveholder's sermon was to just dig the irony out of the hypocrisy of pro-slavery preachers. This speech would be a staple for him whenever he needed it for years to follow. In fact, religious hypocrisy about slavery became, at least in his early life, Douglass's absolute favorite subject.

Alison Stewart: As people wrote about him, they always seem to include his physical description, and they always commented on him being of mixed race and the way he looked. First of all, I would love to know your thoughts on why that is, and did he mind being objectified like that or did he find a way to use it?

David Blight: Oh, it's mostly that he found a way to use it. I think he did mind at times, but this is-- we're talking here the middle of the 19th century. Race consciousness was so complete and so ubiquitous there was no way to avoid it. Yes, Douglass was light-skinned, relatively light-skinned, but clearly a Black person. There was never any question about him passing. He made it perfectly well-known and open that his father was white, and might have even been his master. He told that story over and over and over, and he would play off it. He would joke off it at times and say, "I can do this, you know, and that's probably because of my white father, but I can do that, and that's probably because of my Black mother."

We're talking the 19th century here. We're talking the heyday of racial science. This [unintelligible 00:08:48] is still alive today. People wonder if somebody who's of mixed race, they're, "Wow, they're more intelligent because they got one white parent or something." That's still embedded in people. It's still deep down. No matter how much we learn about how race is a social construction and how much the biology of race is essentially fiction, in the 19th century they didn't know that yet. Douglass would sometimes use it to his advantage. He was very good at converting, shall we say, the awkward truths into humor. Into ways of connecting with his audiences.

Again, it took time. He did not walk out of slavery a fully formed orator by any means. He had to practice it over and over and over, and he learned a lot from the people around him. He learned a lot from Garrison, for example, about how to use the Bible in his rhetoric; and God did he ever. That's a huge part of Douglass's oratory, is particularly his uses of the Hebrew prophets; the Old Testament prophets. What Douglass also learned along the way is how to connect with audiences. What they cared about. What stories would grab them? How he could have them in his hands. We're talking about speeches he would sometimes deliver for an hour, even two hours.

Today you couldn't get away with that. Nobody has the attention span. He became early on a master in this golden age of oratory. You got to remember, oratory in the middle of the 19th century was the only game in town. It was the only entertainment in town. Abolitionists, especially in these early years, were hugely controversial. They were not loved in most towns. In fact, they courted the scorn of their audiences. It was considered a success for some of these traveling troops of abolitionists if they had a few things thrown at them. That meant the audience had been worked up, they had been troubled, they had reached somebody. They just hoped that what was thrown at them wouldn't kill them.

Alison Stewart: They also didn't always agree with one another. There were different philosophies in the anti-slavery movement. Where was Frederick Douglass early in his career?

David Blight: Early on he's a thoroughgoing Garrisonian, which simply means a follower of William Lloyd Garrison. That meant he was in those first five, six, seven years of his speaking career a moral suasionist. That is, the effort was to change the hearts and minds of people, and not so much to change the law or to change the political system. Garrison even taught that political parties were to be avoided. They were dirty. They were complicities with slavery.

Garrison also argued for a kind of radical anarchism of a kind. He called it disunionism. He said what Northern abolitionists really should do is pull out from the Union. Disunify with the South. Not be complicities with slavery. That one was hard to follow. Garrison was also a pacifist; strict pacifist. They called it non-resistance, and Garrison advocated not voting.

Now, some of these were easier for Frederick Douglass and some other Black abolitionists to follow because they had such respect for Garrison, but some of them were not. Douglass though, is a thoroughgoing Garrisonian until he writes that first narrative, 1845. He goes off to England between 1845, fall 1845, and the spring of 1847. It was during that 19-month or so tour of Ireland, Scotland, and England, where Douglass just flowered. He encountered situations with far less racism than he encountered in America, and sometimes no racism at all.

He was embraced by the Irish abolitionists, the Scots loved him, and all over Britain, he made permanent friends in the British reform circles and in the British anti-slavery movement. A group of British abolitionists led by two sisters in Newcastle raised the money to purchase his freedom. Douglass came back from England in '47 a much more independent young man. Now he's 29 years old, and he's beginning to ideologically and even personally break with Garrison. Garrison had been though, a genuine mentor, almost like a father figure. At least an older brother figure. Douglass adored Garrison to some extent, but they will have a big, terrible ideological falling out of course.

Alison Stewart: You write of that relationship between William Lloyd Garrison and Douglass, "In mythic terms, it was important and turbulence." When did the turbulence come in?

David Blight: The turbulence began after 1847, and into '48 and '49 because Douglass wants to be independent. He moved from Massachusetts. Lynn, Massachusetts is where they'd been living. He moved out to Rochester, New York, in Western New York. A city now at the end of the Erie Canal, but a city that was known to be a kind of safe haven for abolitionists. Garrison and his Garrisonians did not want Douglass to do this. He wanted to create his own independent newspaper, he wanted to go on his own. Garrisonians wanted Douglass to stay within the fold because he was their star.

Douglass and Garrison did their final lecture tour together. In 1848 they traveled from Pennsylvania all out through Ohio. They were supposed to do the swing right back into the State of New York. They were operating with what was known as the Oberlin Tent. This was a huge tent that had been created in Oberlin, Ohio, which was an anti-slavery town with an anti-slavery college. They claimed they could get at least 2,000 people into this tent. They would put that baby up out in a farmer's field or on the edge of some village or town. They'd take it down, put it in the wagon, and take it to the next town.

At one point, Garrison began to lose his voice and he got deathly sick. Garrison went on up to Cleveland and was very, very ill with pneumonia and who knows what else, and nearly died. Douglass stayed on the circuit, but that was the last time they ever really collaborated on anything. Because it was right after that that Douglass let Garrison know he was moving lock, stock, and barrel to Rochester, New York, and going to create his own newspaper.

The real breakup though comes in about 1850, '51 when Garrison and the Garrisonians condemned Douglass. Douglass made a full ideological shift to the politics of abolitionism, to advocating the right to vote, and even advocating in certain circumstances the uses of violence against slavery. Also, as you know from reading the book, that there was a scandal involved, and the scandal involved a white woman. An English woman named Julia Griffiths, whom Douglass had met in England. Julia came to America in 1849. Came out to Rochester, lived in the Douglass home for the following three years, and then after that, for three more years, just up the road.

She became Douglass's assistant editor. She became his chief fundraiser. She was an extremely close friend and confidant. She was his right-hand person in running his newspaper and his anti-slavery operation. The Garrisonians though so resented Douglass by '51 that Garrison himself just announced that Douglass was having an affair, a sexual affair, with Julia in his own home under the eyes of his children and his wife. Now, this was vehemently denied, of course, by Douglass and by Julia and by Anna, his wife, but it was the last straw. Douglass and Garrison would never again be good friends. In fact, they wouldn't even appear on the same platform or the same room together again for another 10 years.

Now, everyone's wondering, of course, is that story true. I doubt it. I doubt there was a sexual affair between Douglass and Julia Griffiths. We don't know for sure. What we do know is it was an extremely close friendship and an extraordinarily important friendship. Julia and her sister bought the mortgage on Douglass's house so he wouldn't lose the house. She raised a lot of money to keep his newspaper alive from a well-to-do abolitionist in upstate New York. She was indeed an assistant editor. She kept that newspaper going at times when Douglass himself was either on the road or at times actually quite ill himself.

In fact, I point out in the book that in 1851 for a period of time, Douglass, by all appearances, had a nervous breakdown. I think it's one of the true, crucial turning points in his life. Here was the so-called self-made man who could barely make ends meet, who could barely put food on a table for his now family of five children, and he just came apart. He was trying to end slavery in the United States. There was no reason to believe you were ever going to be able to do that. Julia sort of held the ship together at the printing office.

She also, from her letters we know, would stay up late nights reading songs with Douglass. Sometimes singing favorite hymns, and sometimes also reciting favorite poems by Robert Burns. Douglass was a huge fan of Robert Burns. Also, I should say, Julia Griffiths was the original source of Douglass's now-growing library. She helped purchase some of the first collections that Douglass owned. He would end up with a huge library later in life.

Julia would be gone though, by 1855. She moved back to England, where she married a doctor named Crofts, but Douglass and Julia Griffiths stayed in correspondence the rest of their lives. I should say that what this relationship meant to Douglass, among other things, is that he had a genuine intellectual comrade, whereas his wife Anna, though extremely important in his life, and obviously, the lives of the five children, remained a non-reader, non-writer all of her life.

Alison Stewart: I've been speaking with historian David Blight about his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, from our Full Bio conversation. Coming up next hour, we'll continue our July 4th show by looking at the people in Frederick Douglass's life, his long marriage to his first wife Anna, his five children, and his sometimes turbulent relationship with German feminist and abolitionist, Ottilie Assing. Now let's finish the hour by listening to more of actor Philip Darius Wallace's dramatic reading of Douglass's famous speech, What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?, for the US National Archives.

Philip Darius Wallace: "Fellow citizens, pardon me and allow me to ask, why am I called upon here to speak to you today? What have I, or anyone I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? Am I to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude resulting from the blessing of independence to us?

Would to God, for both your sakes and ours, an affirmative answer would truthfully be returned to the question. Then would my labor be light and my burden easy and delightful. For who would not lend his voice to the hallelujahs of a nation's jubilee when the chains of servitude had been torn from its limb? But, such is not the state of the case. I say, with a sad sense of disparity between us, I am not included within the pale of your glorious anniversary. Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.

The rich inheritance of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, bequeathed by your forefathers, is shared by you, not me. The sunlight that brought life and health to you, brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not ours. You may rejoice."

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.