From the Frontline of the Culture Wars

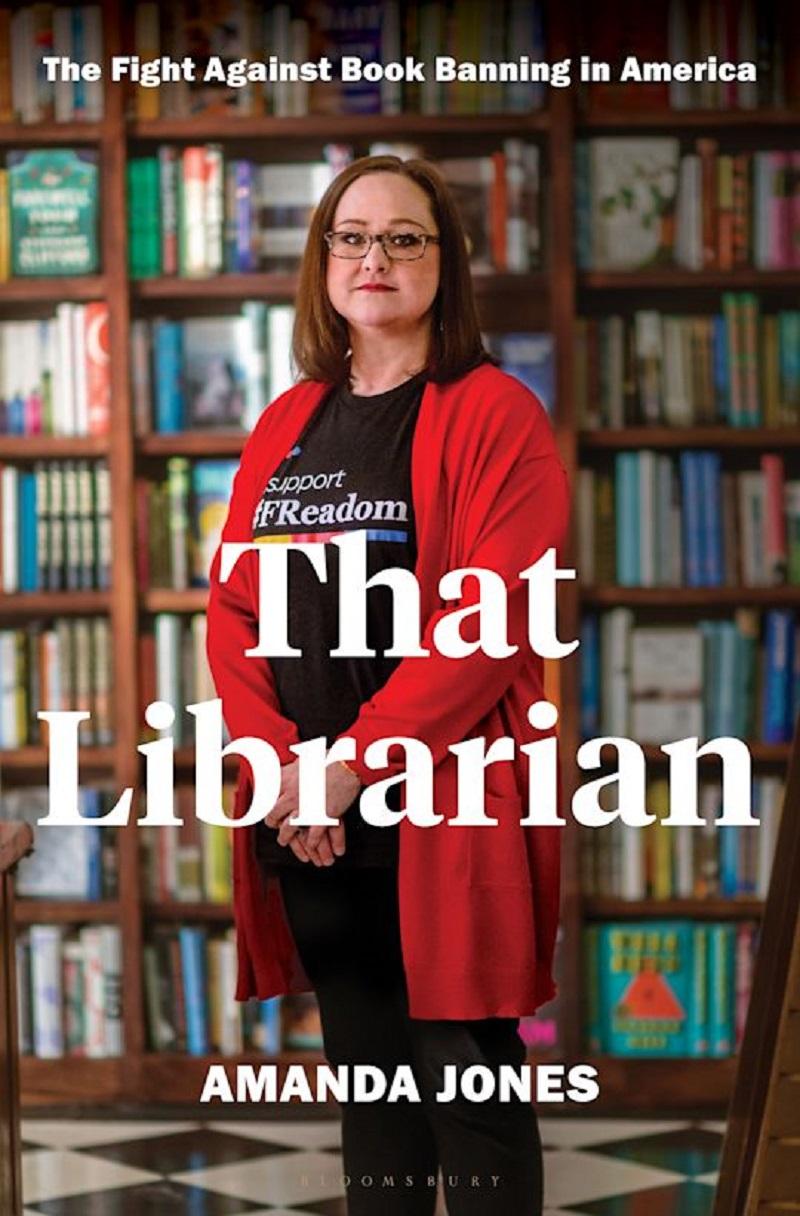

( Bloomsbury, 2024 / Courtesy of the publisher )

Amanda Jones, veteran Louisiana educator and librarian, past president of the Louisiana Association of School Librarians and the author of That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America (Bloomsbury, 2024), talks about pushing back against book bans in her small Louisiana town and the ongoing issue facing librarians across the country.

Brigid Bergin: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. I'm Brigid Bergen in for Brian today. The sad fact is that these days, librarians find themselves on the front lines of the culture wars, and that was brought home clearly to middle school librarian Amanda Jones after she spoke up against book banning and censorship at a board meeting for her local public library system in Livingston Parish, Louisiana, back in 2022. The next thing she knew, she was on the receiving end of a barrage of social media hate, even death threats. She tells her story in a new book called That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America, and she joins us now. Amanda Jones, welcome to WNYC.

Amanda Jones: Hi. Thank you for having me.

Brigid Bergin: Just to start, can you tell us a little bit about your hometown of Watson, Louisiana, and the school where you worked?

Amanda Jones: It's an amazing small town in Livingston Parish, about 20 miles north of Baton Rouge, and I have lived here my entire life. When I was little, we had zero red lights. Now we have two, and we are a close-knit community, or so I thought.

Brigid Bergin: Wow. It sounds like this targeted hate campaign was launched against you after you spoke up at a meeting where I presume you knew a lot of the people, given the way you described the town. What was the meeting, and what did you say that triggered this response?

Amanda Jones: It was a public library board meeting in our public library. I've been a library card holder there since I was five years old. I was not the only one who spoke. There were about 30 others who spoke and said the exact same thing I did. We had a man, a paid extremist, come from out of town to stir up drama. He spoke and said some things that were not true. A board member had listed content and signage on the library board agenda, and she was wanting to set up a committee to look at and examine some books. After the meeting, when we got to look at the list of books, we saw that they were mostly targeted towards the LGBTQIA+ community. I gave a basic censorship speech just about the free speech and the right to speak out and that we already had policies and procedures in place. I mentioned it three times that we already had policies in place to address these issues if anyone had any book concerns but she just didn't want to follow the procedures.

Brigid Bergin: Wow. Your remarks are actually printed at the end of your book, so I can quote a line of your remarks back to you. "All members of our community deserve to be seen, have access to information, and see themselves in our public library collection. Censoring and relocating books and displays is harmful to our community, but will be extremely harmful to our most vulnerable, our children." That sounds like a pretty reasoned thing to say in this setting, but that was enough to trigger that barrage of hate.

Amanda Jones: I thought it was a pretty even-keeled statement. In fact, former President Obama's speechwriter, Terry Szuplat contacted me and told me he thought it was an excellent speech. I'm pretty proud of it but they didn't like it. Of the 30 or so people who spoke, I was the only one that was targeted, and they created some pretty awful untrue memes that rapidly went viral around my community and across the United States.

Brigid Bergin: Listeners, we'd love to have you part of this conversation. Maybe we can even hear from some of your fellow librarians or people who are studying to become librarians. Have you ever had problems like these in your library systems or schools? Has your job changed as a result of the political climate? Anyone else with a question or comment from my guest, Amanda Jones, whose new book is titled That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America you can call us at 212-433-WNYC. Again, the number 212-433-9692. Call or text.

Amanda, you started to tell us about this, but that onslaught of hate over social media that followed your testimony was not just triggering an emotional upheaval, but it also had physical reactions. Can you share some of that with us?

Amanda Jones: It wasn't just online. When I say online, it came at me on every social media platform and on my personal website and emails. They also messaged my family and friends on all social media platforms, even my 97-year-old grandmother. It triggered just panic attacks. I had panic attacks for the first time in my life. I lost chunks of hair. I became anemic because I wasn't eating. Eventually, I had to take a medical leave of absence from my job as a school librarian just because of the onslaught of hate.

Still to this day, I'm being harassed. It's been two years but people videotape me in public, tell me I'm going to hell, tell me God's going to wrap a millstone around my neck and drown me. To be clear, I was raised a Southern Baptist Republican, the same as everybody else in my community. I have read the Bible. I am a Christian. I just don't push my beliefs on other people.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, just to be clear, you said that this meeting that you attended, there was an out-of-town plant who started some of this, but then it was people you knew who were morphing into these online haters?

Amanda Jones: Yes. People I had known my whole life. People who knew me were just joining in. It was this giant dog pile, and I can't wrap my brain around why they've done that. People who were friends of mine, people in positions of power, local politicians joined in the fray and it's disheartening to see people. I have been an educator for 24 years, and there was a woman who told me a few years ago that her child wouldn't have graduated high school if I hadn't helped him learn to read in school. Then I see her joining in and laughing at me, and it's just, it's just a knife to the heart.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, I would think living in a small town that parents objecting to books available for their kids is probably not exactly new. How were parental objections handled in the past?

Amanda Jones: We've never really had any to be honest because there's nothing that we are teaching or nothing in our libraries that are inappropriate. It's a fake controversy. It's not real. There are policies and procedures in place at every library, whether it's a school or a public library. I full-heartedly believe it's every parent's right to object to a book. If they don't like it, their child doesn't have to read it. They have control over what their own child sees and does and learns, but they don't have the right to dictate what other parents want for their children.

That's what we're seeing now. We're seeing not just in my community, but across the United States, where people who maybe aren't even parents in that community or don't even live there are mass-challenging hundreds of books at a time, books they've never even redeveloped. It's not from a place of sincerity. It's a place of causing a fake moral panic.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, I want to pass on a text that we got from one of our listeners who said, "Please pass on love and support to Amanda from the WNYC listeners. She's a hero." Some support from people who are listening to you today. I wonder if you think the same thing that makes libraries and librarians such objects of devotion for many of us also makes them maybe threatening to others. That sense that you're choosing your own books and not your parents or your teachers is maybe a particular type of taboo.

Amanda Jones: The way librarians are being maligned and painted is just funny to me because all of my friends are mostly librarians and educators. We go into our jobs because we love children, we love our patrons, and we want to be community members and support everyone. There's nothing nefarious happening. When you are a librarian, you have a collection development policy, and that collection development policy dictates how you order.

Basically, you order books that the patrons want, and that would be the parents, the students, the teachers, but you use professional reviews. We don't just order anything and everything. We use professional reviews to guide our choices, and we make choices that will allow us to have a diverse collection so that every student and every patron can see themselves in the works on the shelves.

We are not ordering inappropriate books, and we are not placing books that are inappropriate in the wrong categories. There are no sexually explicit materials in children's sections. Again, every parent and every patron has the right to file a challenge form and say, "I don't like that." We can re-examine that. That's okay. We as librarians, we will re-examine that.

Brigid Bergin: If you're just tuning in, I'm Brigid Bergen, filling in for Brian today, and I'm speaking with Louisiana middle school librarian Amanda Jones about her new book, That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America, which tells her story of being targeted for speaking out against censorship of library books. We want to take your calls. If you have questions for Amanda or thoughts about this issue, the number 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. Let's go to Cathy in Rutherford, New Jersey. Cathy, thanks so much for calling.

Cathy: I just wanted to say that librarians are actually on the front lines of one of the worst assaults against our civil liberties, the right to read what we want to read. That is such an innate right in my life. I just have a very hard time wrapping my head around it. I wanted to say librarians really need our support. We have to get out there and stand behind them because they're on the front lines.

Brigid Bergin: Cathy, thanks so much for that call. Go ahead, Amanda. Any reaction to Cathy?

Amanda Jones I was going to say thank you. I have a lot of school librarian friends in New Jersey right now that are being so maligned and defamed, and it is just so horrific. To me, this is a right that we should all want. This is a First Amendment issue that you should want no matter what your political affiliation. An assault on the First Amendment, an assault on our right to read is an attack on all of us.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, we have a listener who texts. "Please tell us the details of the paid extremist, the out-of-town plant. It is fascinating and must be exposed. How much do you know about the person who started some of this conflict at that meeting that has led to what you've gone through recent years?"

Amanda Jones: I know that last week he went on a ten-minute video rant about me and posted my address online and that he has a picture of me framed on his desk, which is very odd and concerning. He works for a dark money nonprofit. Because it's a nonprofit, we can't have access to who their donors are. You will see that when he travels from town to town in Louisiana and he stirs up this fake controversy, the politicians in those areas are usually running for office, and they usually boost his signal. He's just a tool of our politicians.

Eventually, they'll get tired of him and they'll find someone else in some other cause. There's not much we can look at because of the way they're a dark money nonprofit, and we can't see their donors.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, a listener texts "Parents who object to certain books should have to meet with a principal and librarian to prove they've read and understood the book they wanted banned." How much have you encountered people objecting to certain titles that perhaps they don't fully understand, or you have a sense that they haven't actually read?

Amanda Jones: Most challenged policies ask that the person objecting does read the book in whole to get a sense of what the entire book is. I will say I've never had any formal challenges, but a few years ago, I did have a parent question a book that I read aloud to the class called The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander, and it won so many awards, Coretta Scott King, Caldecott, Newbery. She objected to it, but she hadn't read it. I called her and I said, "Hey, let me explain. Let me read this book to you. Let me tell you. Once I read the book to her and once I explained, she was like, "There's nothing wrong with this." I'm like, "Exactly."

I can't have a one-on-one conversation with every person in my community. At some point, the community has to trust the librarians and know that we didn't go into this field with some nefarious plan. We love our community, and we love children, and we want to help everybody in the community, not just one section. We're there for every community member, no matter their race, gender, religion, socioeconomic status.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, picking up on that idea that part of how you reached this understanding with this parent was to actually explain and teach and help them understand what something was about. What does the news that yesterday Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry banned the teaching of critical race theory in schools in the state mean to teachers and librarians heading into the school year?

Amanda Jones: First of all, nobody in k-12 schools are teaching a college-level theory course. It's a misrepresentation of what's being taught. it's very shameful that my governor would use teachers and librarians in this manner for pandering for political power. It's divisive on purpose. The Louisiana Department of Education sets the standards and the lessons, and it's mostly a scripted curriculum, especially in history.

Yes, there will be discussions on race and racism. It's black history. Nobody is teaching critical race theory. It's just very fake and it reminds me, I happened to see yesterday on Twitter or X, President Biden tweeted, "Darkness and denialism can hide much, but they erase nothing. We should know everything, the good, the bad, and the truth of who we are as a nation. That's what great nations do. I'm going to stop right there because I don't have many nice things to say about our governor at this time.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, a big part of your story is what you eventually did in response to this campaign of hate. I think the book and your appearance here are probably part of that. How have you answered the haters?

Amanda Jones: I try to answer with kindness and empathy and love because their message is one of divisiveness and hatefulness and I don't want to be like that. It's not good for my heart, first of all. I am an educator, and I choose to be an example to the children of my community. The children are watching, and what kind of example are we setting when we are spreading lies and rumors, and hate about their children's librarians and their teachers? It's horrific. I try to respond with hate and kindness, and I always try to think of what would our former First Lady Michelle Obama say? When they go low, you go high. I've tried very hard, and it's a work in progress, but I am trying.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, one of our listeners texted, "Do we know what percentage of librarians are women? This type of hate seems to often be targeted towards women." Do you have a sense of that?

Amanda Jones: Yes. I don't know the exact statistics on that but we are a largely female-dominated field. Librarians and educators are largely female, and that has brought up a lot that we are doing this to women. I have a lot. I have many, many school librarian friends all across the country, and I know hundreds of librarians who have been targeted and attacked. While there have been some males, the majority of the people being attacked are females. I don't think that's a coincidence.

Brigid Bergin: Another listener texted, "Sounds like a dystopian version of the music Mandev going town to town, spreading hate rather than joy." Amanda, I'm curious. I saw you tweeted out a roadmap of attacks on libraries, and that really goes pretty well beyond books. Is that right?

Amanda Jones: Oh, yes. The books are the starting point to devalue and eradicate libraries. I am fortunate to be one of the founding members of Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship, and I created a roadmap. It starts with the books. There's a post made of a book out of context. Then you will see library board and school board takeovers. Then you see the politicians jumping in on the bandwagon.

What they do is they stir up the flames to these things that are not really happening so they can come in with solutions to problems that don't exist.

You then see anti-library legislation. We've seen it sweeping all across the United States. We had nine anti-library bills in Louisiana last year. We defeated seven of them. It's all geared towards marginalizing certain authors and characters and stories, but it's also about defunding things like public libraries and public schools. The same people who are attacking the books, they're going to profit from charter schools and privatized libraries.

Brigid Bergin: I want to go to one of our callers. Let's go to Susan in Chatham, New Jersey. Susan, thanks for calling WNYC.

Susan: Hi. I'm happy to talk to you not specifically about the book, but let me just say one thing first. [unintelligible 00:19:04]

Brigid Bergin: Susan, I'm sorry. It sounds like you're a little too far away from your phone. We can't hear you, so we're going to put you back on hold for now. Let's go to Alan in Brooklyn. Alan, thanks for calling.

Alan: Good morning. This is not a new idea. It just seems to bear repeating that people have the greatest desire to ban reading by others of material they haven't been exposed to. The less people read because they're getting their exposure to words on screens, the less tolerance people have of ideas that others may hold. Phones, by their nature, because the algorithms that guide the feeds on Facebook and elsewhere are narrow-casting material that the reader or the phone holder already finds familiar. It's not exposing them to new ideas that might be in other book materials. The general trend is the less reading we have, the more desire there is to ban reading by others because people fear what they don't know.

Brigid Bergin: Alan, thank you so much for that call. Let's try Susan again in Chatham, New Jersey. Susan, do we have you now?

Susan: Yes. Thank you. Basically, what I want to say is that I don't know what people are so afraid of in the books. We have children's libraries. We have librarians who know very well what a student should take out and shouldn't and would never do anything to harm that child. The thing that I think parents should be thinking more about throwing in the fire is the kids' cell phones. They could have learned a lot worse things from their cell phones, and now they want to keep them in the classroom, which is ridiculous. My daughter is a teacher. It's hard enough to keep their attention.

Brigid Bergin: Speaking of cell phones, I think we lost Susan there. Thank you for that call Susan, and thanks for bringing up a topic we talked a little bit about yesterday, cellphones in schools. I think it will be a hot topic for the upcoming school year. Amanda, any reactions to either of those callers? It is true. Students have access to an abundance of unfiltered information through those smartphones that isn't curated the way a library is.

Amanda Jones: It's true. I actually wrote an article for school library journal last year called The Danger In Their Hands about a lesson I did with all 700 of my students. The things that we discussed, the things that they seed on their phones and on their computers was shocking. I asked them the types of things that they're hearing and seeing online and it was horrific. I asked the had they ever seen anything in a library, and not a single one of them had. That tells me a lot.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, before I let you go, I want to get in just a couple more questions quickly. Your book has advice to offer, and I want to hear some of that. First, what advice do you give to parents who maybe have been told by a friend that there are pornographic books in the kids' section of the library? How do you fact-check something like that?

Amanda Jones: See, that's easy to fact-check, actually, but people don't tend to want to fact-check it. Pretty much every school library catalog is online, and every public library catalog is online. All you have to do is go to the public library or the school library's catalog, type in the book, and see where it's at if it's even in there. There was a wild rumor about a book in our town, and I pointed out they were saying it was in the children's section next to Green Eggs and Ham, and it was in the adult section.

It's very easy. All you have to do is look it up but it's so much more fun to share false information. I will say, besides checking online, reach out to those librarians not with accusations, just with questions, because we love to talk to parents and patrons.

Brigid Bergin: What about advice for those librarians or those contemplating library? School?

Amanda Jones: Being a librarian is the best job in the world besides being a classroom teacher because I'm a former classroom teacher. It's the best job in the world. What I'm afraid of is that our country is making it not the best job in the world anymore. I think this moment in history will soon be over hopefully. It's going to take more citizens speaking out because I know the librarians are speaking out. I know the authors are speaking out. We need everyday citizens. Pay attention to your board meetings. Go and speak if you're able. Vote. Just stay in the know. If you hear something false, look into it and try to dispel that rumor but do it with kindness and empathy, and love. Don't do it with hate.

Brigid Bergin: Finally, Amanda, would you do it all again?

Amanda Jones: Oh, absolutely. 100%.

Brigid Bergin: Before we let you go, I need to tell you again, we've gotten lots of texts of support for you and the work you do. I want to get one more caller in very briefly. Maggie in Brooklyn. I think she wants to write a little love letter to the library. Maggie, let's wrap up with you.

Maggie: Hey, how are you doing? I just wanted to say as a child in the '60s, I was a very big reader. My proudest possession was when I got my library card. My mom was an educator, and her focus was having a kid who loved reading and I did. She let me read anything. What I realized later on was there was a lot of stuff I read that I didn't understand at the time. There was even a lot of stuff I read as a young adult that I didn't understand fully at the time. That's what I think. If the material is too mature for kids, they won't get it.

Anyway, I just always felt like the library was my little sanctuary and librarians-- I had a job in the library reshelveing books which I was very proud of at the time. I just wanted to give a love letter to the librarians because they help you love books. I think a love of reading just opens the door to everything else in life that will help you.

Brigid Bergin: Maggie, thank you for that call. Thank you for that love letter to libraries and librarians. Amanda Jones is a veteran Louisiana educator and librarian, past president of the Louisiana Association of School Librarians, and author of That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America. Amanda, thank you, and good luck.

Amanda Jones: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.